Modern China

The Neolithic period saw increasingly complex polities begin to emerge along the Yellow and Yangtze rivers. The Erlitou culture in the central plains of China is sometimes identified with the Xia dynasty (3rd millennium BC) of traditional Chinese historiography. The earliest surviving written Chinese dates to roughly 1250 BC, consisting of divinations inscribed on oracle bones. Chinese bronze inscriptions, ritual texts dedicated to ancestors, form another large corpus of early Chinese writing. The earliest strata of received literature in Chinese include poetry, divination, and records of official speeches. China is believed to be one of a very few loci of independent invention of writing, and the earliest surviving records display an already-mature written language. The culture remembered by the earliest extant literature is that of the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046 – 256 BC), China's Axial Age, during which the Mandate of Heaven was introduced, and foundations laid for philosophies such as Confucianism, Taoism, Legalism, and Wuxing.

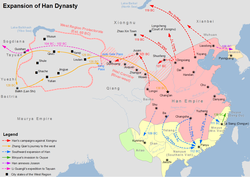

China was first united under a single imperial state by Qin Shi Huang in 221 BC. Orthography, weights, measures, and law were all standardized. Shortly thereafter, China entered its classical era with the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), marking a critical period. A term for the Chinese language is still "Han language", and the dominant Chinese ethnic group is known as Han Chinese. The Chinese empire reached some of its farthest geographical extents during this period. Confucianism was officially sanctioned and its core texts were edited into their received forms. Wealthy landholding families independent of the ancient aristocracy began to wield significant power. Han technology can be considered on par with that of the contemporaneous Roman Empire: mass production of paper aided the proliferation of written documents, and the written language of this period was employed for millennia afterwards. China became known internationally for its sericulture. When the Han imperial order finally collapsed after four centuries, China entered an equally lengthy period of disunity, during which Buddhism began to have a significant impact on Chinese culture, while Calligraphy, art, historiography, and storytelling flourished. Wealthy families in some cases became more powerful than the central government. The Yangtze River valley was incorporated into the dominant cultural sphere.

A period of unity began in 581 with the Sui dynasty, which soon gave way to the long-lived Tang dynasty (608–907), regarded as another Chinese golden age. The Tang dynasty saw flourishing developments in science, technology, poetry, economics, and geographical influence. China's only officially recognized empress, Wu Zetian, reigned during the dynasty's first century. Buddhism was adopted by Tang emperors. "Tang people" is the other common demonym for the Han ethnic group. After the Tang fractured, the Song dynasty (960–1279) saw the maximal extent of imperial Chinese cosmopolitan development. Mechanical printing was introduced, and many of the earliest surviving witnesses of certain texts are wood-block prints from this era. Song scientific advancement led the world, and the imperial examination system gave ideological structure to the political bureaucracy. Confucianism and Taoism were fully knit together in Neo-Confucianism.

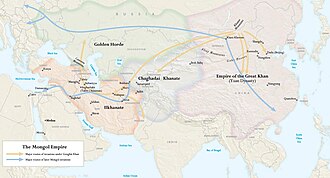

Eventually, the Mongol Empire conquered all of China, establishing the Yuan dynasty in 1271. Contact with Europe began to increase during this time. Achievements under the subsequent Ming dynasty (1368–1644) include global exploration, fine porcelain, and many extant public works projects, such as those restoring the Grand Canal and Great Wall. Three of the four Classic Chinese Novels were written during the Ming. The Qing dynasty that succeeded the Ming was ruled by ethnic Manchu people. The Qianlong emperor (r. 1735–1796) commissioned a complete encyclopaedia of imperial libraries, totaling nearly a billion words. Imperial China reached its greatest territorial extent of during the Qing, but China came into increasing conflict with European powers, culminating in the Opium Wars and subsequent unequal treaties.

The 1911 Xinhai Revolution, led by Sun Yat-sen and others, created the Republic of China. From 1927 to 1949, a costly civil war roiled between the Republican government under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communist-aligned Chinese Red Army, interrupted by the industrialized Empire of Japan invading the divided country until its defeat in the Second World War.

After the Communist victory, Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, with the ROC retreating to Taiwan. Both governments still claim sole legitimacy of the entire mainland area. The PRC has slowly accumulated the majority of diplomatic recognition, and Taiwan's status remains disputed to this day. From 1966 to 1976, the Cultural Revolution in mainland China helped consolidate Mao's power towards the end of his life. After his death, the government began economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping, and became the world's fastest-growing major economy. China had been the most populous nation in the world for decades since its unification, until it was surpassed by India in 2023.

Prehistory

Paleolithic (1.7 Ma – 12 ka)

The archaic human species of Homo erectus arrived in Eurasia sometime between 1.3 and 1.8 million years ago (Ma) and numerous remains of its subspecies have been found in what is now China. The oldest of these is the southwestern Yuanmou Man (元谋人; in Yunnan), dated to c. 1.7 Ma, which lived in a mixed bushland-forest environment alongside chalicotheres, deer, the elephant Stegodon, rhinos, cattle, pigs, and the giant short-faced hyena. The better-known Peking Man (北京猿人; near Beijing) of 700,000–400,000 BP, was discovered in the Zhoukoudian cave alongside scrapers, choppers, and, dated slightly later, points, burins, and awls. Other Homo erectus fossils have been found widely throughout the region, including the northwestern Lantian Man in Shaanxi, as well minor specimens in northeastern Liaoning and southern Guangdong. The dates of most Paleolithic sites were long debated but have been more reliably established based on modern magnetostratigraphy: Majuangou at 1.66–1.55 Ma, Lanpo at 1.6 Ma, Xiaochangliang at 1.36 Ma, Xiantai at 1.36 Ma, Banshan at 1.32 Ma, Feiliang at 1.2 Ma and Donggutuo at 1.1 Ma. Evidence of fire use by Homo erectus occurred between 1–1.8 million years BP at the archaeological site of Xihoudu, Shanxi Province.

The circumstances surrounding the evolution of Homo erectus to contemporary H. sapiens is debated; the three main theories include the dominant "Out of Africa" theory (OOA), the regional continuity model and the admixture variant of the OOA hypothesis. Regardless, the earliest modern humans have been dated to China at 120,000–80,000 BP based on fossilized teeth discovered in Fuyan Cave of Dao County, Hunan. The larger animals which lived alongside these humans include the extinct Ailuropoda baconi panda, the Crocuta ultima hyena, the Stegodon, and the giant tapir. Evidence of Middle Palaeolithic Levallois technology has been found in the lithic assemblage of Guanyindong Cave site in southwest China, dated to approximately 170,000–80,000 years ago.

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age in China is considered to have begun about 10,000 years ago. Because the Neolithic is conventionally defined by the presence of agriculture, it follows that the Neolithic began at different times in the various regions of what is now China. Agriculture in China developed gradually, with initial domestication of a few grains and animals gradually expanding with the addition of many others over subsequent millennia. The earliest evidence of cultivated rice, found by the Yangtze River, was carbon-dated to 8,000 years ago. Early evidence for millet agriculture in the Yellow River valley was radiocarbon-dated to about 7000 BC. The Jiahu site is one of the best preserved early agricultural villages (7000 to 5800 BC). At Damaidi in Ningxia, 3,172 cliff carvings dating to 6000–5000 BC have been discovered, "featuring 8,453 individual characters such as the sun, moon, stars, gods and scenes of hunting or grazing", according to researcher Li Xiangshi. Written symbols, sometimes called proto-writing, were found at the site of Jiahu, which is dated around 7000 BC, Damaidi around 6000 BC, Dadiwan from 5800 BC to 5400 BC, and Banpo dating from the 5th millennium BC. With agriculture came increased population, the ability to store and redistribute crops, and the potential to support specialist craftsmen and administrators, which may have existed at late Neolithic sites like Taosi and the Liangzhu culture in the Yangtze delta. The cultures of the middle and late Neolithic in the central Yellow River valley are known, respectively, as the Yangshao culture (5000 BC to 3000 BC) and the Longshan culture (3000 BC to 2000 BC). Pigs and dogs were the earliest-domesticated animals in the region, and after about 3000 BC domesticated cattle and sheep arrived from Western Asia. Wheat also arrived at this time but remained a minor crop. Fruit such as peaches, cherries and oranges, as well as chickens and various vegetables, were also domesticated in Neolithic China.

Bronze Age

Bronze artifacts have been found at the Majiayao culture site (between 3100 and 2700 BC). The Bronze Age is also represented at the Lower Xiajiadian culture (2200–1600 BC) site in northeast China. Sanxingdui located in what is now Sichuan is believed to be the site of a major ancient city, of a previously unknown Bronze Age culture (between 2000 and 1200 BC). The site was first discovered in 1929 and then re-discovered in 1986. Chinese archaeologists have identified the Sanxingdui culture to be part of the state of Shu, linking the artifacts found at the site to its early legendary kings.

Ferrous metallurgy begins to appear in the late 6th century in the Yangtze valley. A bronze hatchet with a blade of meteoric iron excavated near the city of Gaocheng in Shijiazhuang (now Hebei) has been dated to the 14th century BC. An Iron Age culture of the Tibetan Plateau has tentatively been associated with the Zhang Zhung culture described in early Tibetan writings.

Ancient China

Chinese historians in later periods were accustomed to the notion of one dynasty succeeding another, but the political situation in early China was much more complicated. Hence, as some scholars of China suggest, the Xia and the Shang can refer to political entities that existed concurrently, just as the early Zhou existed at the same time as the Shang. This bears similarities to how China, both contemporaneously and later, has been divided into states that were not one region, legally or culturally.

The earliest period once considered historical was the legendary era of the sage-emperors Yao, Shun, and Yu. Traditionally, the abdication system was prominent in this period, with Yao yielding his throne to Shun, who abdicated to Yu, who founded the Xia dynasty.

Xia dynasty (c. 2070 – c. 1600 BC)

The Xia dynasty (c. 2070 – c. 1600 BC) is the earliest of the three dynasties described in much later traditional historiography, which includes the Bamboo Annals and Sima Qian's Shiji (c. 91 BC). The Xia is generally considered mythical by Western scholars, but in China it is usually associated with the early Bronze Age site at Erlitou (1900–1500 BC) in Henan that was excavated in 1959. Since no writing was excavated at Erlitou or any other contemporaneous site, there is not enough evidence to prove whether the Xia dynasty ever existed. Some archaeologists claim that the Erlitou site was the capital of the Xia. In any case, the site of Erlitou had a level of political organization that would not be incompatible with the legends of Xia recorded in later texts. More importantly, the Erlitou site has the earliest evidence for an elite who conducted rituals using cast bronze vessels, which would later be adopted by the Shang and Zhou.

Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC)

Both archaeological evidence like oracle bones and bronzes, as well as transmitted texts attest the historical existence of the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC). Findings from the earlier Shang period come from excavations at Erligang (modern Zhengzhou). Findings have been found at Yinxu (near modern Anyang, Henan), the site of the final Shang capital during the Late Shang period (c. 1250–1050 BC). The findings at Anyang include the earliest written record of the Chinese so far discovered: inscriptions of divination records in ancient Chinese writing on the bones or shells of animals—the oracle bones, dating from c. 1250 – c. 1046 BC.

A series of at least twenty-nine kings reigned over the Shang dynasty. Throughout their reigns, according to the Shiji, the capital city was moved six times. The final and most important move was to Yin during the reign of Wu Ding c. 1250 BC. The term Yin dynasty has been synonymous with the Shang dynasty in history, although it has lately been used to refer specifically to the latter half of the Shang dynasty.

Although written records found at Anyang confirm the existence of the Shang dynasty, Western scholars are often hesitant to associate settlements that are contemporaneous with the Anyang settlement with the Shang dynasty. For example, archaeological findings at Sanxingdui suggest a technologically advanced civilization culturally unlike Anyang. The evidence is inconclusive in proving how far the Shang realm extended from Anyang. The leading hypothesis is that Anyang, ruled by the same Shang in the official history, coexisted and traded with numerous other culturally diverse settlements in the area that is now referred to as China proper.

Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BC)

The Zhou dynasty (1046 BC to about 256 BC) is the longest-lasting dynasty in Chinese history, though its power declined steadily over the almost eight centuries of its existence. In the late 2nd millennium BC, the Zhou dynasty arose in the Wei River valley of modern western Shaanxi Province, where they were appointed Western Protectors by the Shang. A coalition led by the ruler of the Zhou, King Wu, defeated the Shang at the Battle of Muye. They took over most of the central and lower Yellow River valley and enfeoffed their relatives and allies in semi-independent states across the region. Several of these states eventually became more powerful than the Zhou kings.

The kings of Zhou invoked the concept of the Mandate of Heaven to legitimize their rule, a concept that was influential for almost every succeeding dynasty. Like Shangdi, Heaven (tian) ruled over all the other gods, and it decided who would rule China. It was believed that a ruler lost the Mandate of Heaven when natural disasters occurred in great number, and when, more realistically, the sovereign had apparently lost his concern for the people. In response, the royal house would be overthrown, and a new house would rule, having been granted the Mandate of Heaven.

The Zhou established two capitals Zongzhou (near modern Xi'an) and Chengzhou (Luoyang), with the king's court moving between them regularly. The Zhou alliance gradually expanded eastward into Shandong, southeastward into the Huai River valley, and southward into the Yangtze River valley.

Spring and Autumn period (722–476 BC)

In 771 BC, King You and his forces were defeated in the Battle of Mount Li by rebel states and Quanrong barbarians. The rebel aristocrats established a new ruler, King Ping, in Luoyang, beginning the second major phase of the Zhou dynasty: the Eastern Zhou period, which is divided into the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. The former period is named after the famous Spring and Autumn Annals. The sharply reduced political authority of the royal house left a power vacuum at the center of the Zhou culture sphere. The Zhou kings had delegated local political authority to hundreds of settlement states, some of them only as large as a walled town and surrounding land. These states began to fight against one another and vie for hegemony. The more powerful states tended to conquer and incorporate the weaker ones, so the number of states declined over time. By the 6th century BC most small states had disappeared by being annexed and just a few large and powerful principalities remained. Some southern states, such as Chu and Wu, claimed independence from the Zhou, who undertook wars against some of them (Wu and Yue). Many new cities were established in this period and society gradually became more urbanized and commercialized. Many famous individuals such as Laozi, Confucius and Sun Tzu lived during this chaotic period.

Conflict in this period occurred both between and within states. Warfare between states forced the surviving states to develop better administrations to mobilize more soldiers and resources. Within states there was constant jockeying between elite families. For example, the three most powerful families in the Jin state—Zhao, Wei and Han—eventually overthrew the ruling family and partitioned the state between them.

The Hundred Schools of Thought of classical Chinese philosophy began blossoming during this period and the subsequent Warring States period. Such influential intellectual movements as Confucianism, Taoism, Legalism and Mohism were founded, partly in response to the changing political world. The first two philosophical thoughts would have an enormous influence on Chinese culture.

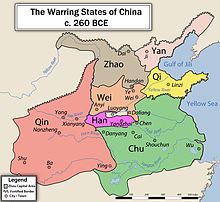

Warring States period (476–221 BC)

After further political consolidations, seven prominent states remained during the 5th century BC. The years in which these states battled each other is known as the Warring States period. Though the Zhou king nominally remained as such until 256 BC, he was largely a figurehead that held little real power.

Numerous developments were made during this period in the areas of culture and mathematics—including the Zuo Zhuan within the Spring and Autumn Annals (a literary work summarizing the preceding Spring and Autumn period), and the bundle of 21 bamboo slips from the Tsinghua collection, dated to 305 BC—being the world's earliest known example of a two-digit, base-10 multiplication table. The Tsinghua collection indicates that sophisticated commercial arithmetic was already established during this period.

As neighboring territories of the seven states were annexed (including areas of modern Sichuan and Liaoning), they were now to be governed under an administrative system of commanderies and prefectures. This system had been in use elsewhere since the Spring and Autumn period, and its influence on administration would prove resilient—its terminology can still be seen in the contemporaneous sheng and xian ("provinces" and "counties") of contemporary China.

The state of Qin became dominant in the waning decades of the Warring States period, conquering the Shu capital of Jinsha on the Chengdu Plain; and then eventually driving Chu from its place in the Han River valley. Qin imitated the administrative reforms of the other states, thereby becoming a powerhouse. Its final expansion began during the reign of Ying Zheng, ultimately unifying the other six regional powers, and enabling him to proclaim himself as China's first emperor—known to history as Qin Shi Huang.

Imperial era

Early imperial China

Qin dynasty (221–206 BC)

Ying Zheng's establishment of the Qin dynasty (秦朝) in 221 BC effectively formalised the region as a true empire for the first time in Chinese history, rather than a state, and its pivotal status probably led to "Qin" (秦) later evolving into the Western term "China". To emphasise his sole rule, Zheng proclaimed himself Shi Huangdi (始皇帝; "First Emperor"); the Huangdi title, derived from Chinese mythology, became the standard for subsequent rulers. Based in Xianyang, the empire was a centralized bureaucratic monarchy, a governing scheme which dominated the future of Imperial China. In an effort to improve the Zhou's perceived failures, this system consisted of more than 36 commanderies (郡; jun), made up of counties (县; xian) and progressively smaller divisions, each with a local leader.

Many aspects of society were informed by Legalism, a state ideology promoted by the emperor and his chancellor Li Si that was introduced at an earlier time by Shang Yang. In legal matters this philosophy emphasised mutual responsibility in disputes and severe punishments for crime, while economic practices included the general encouragement of agriculture and repression of trade. Reforms occurred in weights and measures, writing styles (seal script) and metal currency (Ban Liang), all of which were standardized. Traditionally, Qin Shi Huang is regarded as ordering a mass burning of books and the live burial of scholars under the guise of Legalism, though contemporary scholars express considerable doubt on the historicity of this event. Despite its importance, Legalism was probably supplemented in non-political matters by Confucianism for social and moral beliefs and the five-element Wuxing (五行) theories for cosmological thought.

The Qin administration kept exhaustive records on their population, collecting information on their sex, age, social status and residence. Commoners, who made up over 90% of the population, "suffered harsh treatment" according to the historian Patricia Buckley Ebrey, as they were often conscripted into forced labor for the empire's construction projects. This included a massive system of imperial highways in 220 BC, which ranged around 4,250 miles (6,840 km) altogether. Other major construction projects were assigned to the general Meng Tian, who concurrently led a successful campaign against the northern Xiongnu peoples (210s BC), reportedly with 300,000 troops. Under Qin Shi Huang's orders, Meng supervised the combining of numerous ancient walls into what came to be known as the Great Wall of China and oversaw the building of a 500 miles (800 km) straight highway between northern and southern China. The emperor also oversaw the construction of his monumental mausoleum, which includes the well known Terracotta Army.

After Qin Shi Huang's death the Qin government drastically deteriorated and eventually capitulated in 207 BC after the Qin capital was captured and sacked by rebels, which would ultimately lead to the establishment of the Han Empire.

Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220)

Western Han

The Han dynasty was founded by Liu Bang, who emerged victorious in the Chu–Han Contention that followed the fall of the Qin dynasty. A golden age in Chinese history, the Han dynasty's long period of stability and prosperity consolidated the foundation of China as a unified state under a central imperial bureaucracy, which was to last intermittently for most of the next two millennia. During the Han dynasty, territory of China was extended to most of the China proper and to areas far west. Confucianism was officially elevated to orthodox status and was to shape the subsequent Chinese civilization. Art, culture and science all advanced to unprecedented heights. With the profound and lasting impacts of this period of Chinese history, the dynasty name "Han" had been taken as the name of the Chinese people, now the dominant ethnic group in modern China, and had been commonly used to refer to Chinese language and written characters.

After the initial laissez-faire policies of Emperors Wen and Jing, the ambitious Emperor Wu brought the empire to its zenith. To consolidate his power, he disenfranchised the majority of imperial relatives, appointing military governors to control their former lands. As a further step, he extended patronage to Confucianism, which emphasizes stability and order in a well-structured society. Imperial Universities were established to support its study. At the urging of his Legalist advisors, however, he also strengthened the fiscal structure of the dynasty with government monopolies.

Major military campaigns were launched to weaken the nomadic Xiongnu Empire, limiting their influence north of the Great Wall. Along with the diplomatic efforts led by Zhang Qian, the sphere of influence of the Han Empire extended to the states in the Tarim Basin, opened up the Silk Road that connected China to the west, stimulating bilateral trade and cultural exchange. To the south, various small kingdoms far beyond the Yangtze River Valley were formally incorporated into the empire.

Emperor Wu also dispatched a series of military campaigns against the Baiyue tribes. The Han annexed Minyue in 135 BC and 111 BC, Nanyue in 111 BC, and Dian in 109 BC. Migration and military expeditions led to the cultural assimilation of the south. It also brought the Han into contact with kingdoms in Southeast Asia, introducing diplomacy and trade.

After Emperor Wu the empire slipped into gradual stagnation and decline. Economically, the state treasury was strained by excessive campaigns and projects, while land acquisitions by elite families gradually drained the tax base. Various consort clans exerted increasing control over strings of incompetent emperors and eventually the dynasty was briefly interrupted by the usurpation of Wang Mang.

Xin dynasty

In AD 9 the usurper Wang Mang claimed that the Mandate of Heaven called for the end of the Han dynasty and the rise of his own, and he founded the short-lived Xin dynasty. Wang Mang started an extensive program of land and other economic reforms, including the outlawing of slavery and land nationalization and redistribution. These programs, however, were never supported by the landholding families, because they favored the peasants. The instability of power brought about chaos, uprisings, and loss of territories. This was compounded by mass flooding of the Yellow River; silt buildup caused it to split into two channels and displaced large numbers of farmers. Wang Mang was eventually killed in Weiyang Palace by an enraged peasant mob in AD 23.

Eastern Han

Emperor Guangwu reinstated the Han dynasty with the support of landholding and merchant families at Luoyang, east of the former capital Xi'an. Thus, this new era is termed the Eastern Han dynasty. With the capable administrations of Emperors Ming and Zhang, former glories of the dynasty were reclaimed, with brilliant military and cultural achievements. The Xiongnu Empire was decisively defeated. The diplomat and general Ban Chao further expanded the conquests across the Pamirs to the shores of the Caspian Sea, thus reopening the Silk Road, and bringing trade, foreign cultures, along with the arrival of Buddhism. With extensive connections with the west, the first of several Roman embassies to China were recorded in Chinese sources, coming from the sea route in AD 166, and a second one in AD 284.

The Eastern Han dynasty was one of the most prolific eras of science and technology in ancient China, notably the historic invention of papermaking by Cai Lun, and the numerous scientific and mathematical contributions by the famous polymath Zhang Heng.

Six Dynasties

Three Kingdoms (AD 220–280)

By the 2nd century, the empire declined amidst land acquisitions, invasions, and feuding between consort clans and eunuchs. The Yellow Turban Rebellion broke out in AD 184, ushering in an era of warlords. In the ensuing turmoil, three states emerged, trying to gain predominance and reunify the land, giving this historical period its name. The classic historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms dramatizes events of this period.

The warlord Cao Cao reunified the north in 208, and in 220 his son accepted the abdication of Emperor Xian of Han, thus initiating the Wei dynasty. Soon, Wei's rivals Shu and Wu proclaimed their independence. This period was characterized by a gradual decentralization of the state that had existed during the Qin and Han dynasties, and an increase in the power of great families.

In 266, the Jin dynasty overthrew the Wei and later unified the country in 280, but this union was short-lived.