Featured articles –

The hydrogen atom is a Kepler problem, since it comprises two charged particles interacting by Coulomb's law of electrostatics, another inverse-square central force. The LRL vector was essential in the first quantum mechanical derivation of the spectrum of the hydrogen atom, before the development of the Schrödinger equation. However, this approach is rarely used today. (Full article...)

In mathematics, zero is an even number. In other words, its parity—the quality of an integer being even or odd—is even. This can be easily verified based on the definition of "even": zero is an integer multiple of 2, specifically 0 × 2. As a result, zero shares all the properties that characterize even numbers: for example, 0 is neighbored on both sides by odd numbers, any decimal integer has the same parity as its last digit—so, since 10 is even, 0 will be even, and if y is even then y + x has the same parity as x—indeed, 0 + x and x always have the same parity.

Zero also fits into the patterns formed by other even numbers. The parity rules of arithmetic, such as even − even = even, require 0 to be even. Zero is the additive identity element of the group of even integers, and it is the starting case from which other even natural numbers are recursively defined. Applications of this recursion from graph theory to computational geometry rely on zero being even. Not only is 0 divisible by 2, it is divisible by every power of 2, which is relevant to the binary numeral system used by computers. In this sense, 0 is the "most even" number of all. (Full article...)

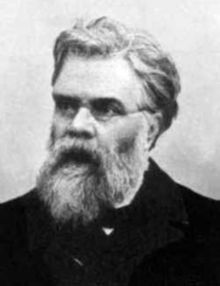

Émile Michel Hyacinthe Lemoine (French: [emil ləmwan]; 22 November 1840 – 21 February 1912) was a French civil engineer and a mathematician, a geometer in particular. He was educated at a variety of institutions, including the Prytanée National Militaire and, most notably, the École Polytechnique. Lemoine taught as a private tutor for a short period after his graduation from the latter school.

Lemoine is best known for his proof of the existence of the Lemoine point (or the symmedian point) of a triangle. Other mathematical work includes a system he called Géométrographie and a method which related algebraic expressions to geometric objects. He has been called a co-founder of modern triangle geometry, as many of its characteristics are present in his work. (Full article...)

Shen Kuo (Chinese: 沈括; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁), was a Chinese polymath, scientist, and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen was a master in many fields of study including mathematics, optics, and horology. In his career as a civil servant, he became a finance minister, governmental state inspector, head official for the Bureau of Astronomy in the Song court, Assistant Minister of Imperial Hospitality, and also served as an academic chancellor. At court his political allegiance was to the Reformist faction known as the New Policies Group, headed by Chancellor Wang Anshi (1021–1085).

In his Dream Pool Essays or Dream Torrent Essays (夢溪筆談; Mengxi Bitan) of 1088, Shen was the first to describe the magnetic needle compass, which would be used for navigation (first described in Europe by Alexander Neckam in 1187). Shen discovered the concept of true north in terms of magnetic declination towards the north pole, with experimentation of suspended magnetic needles and "the improved meridian determined by Shen's [astronomical] measurement of the distance between the pole star and true north". This was the decisive step in human history to make compasses more useful for navigation, and may have been a concept unknown in Europe for another four hundred years (evidence of German sundials made circa 1450 show markings similar to Chinese geomancers' compasses in regard to declination). (Full article...)

Emery Molyneux (/ˈɛməri ˈmɒlɪnoʊ/ EM-ər-ee MOL-in-oh; died June 1598) was an English Elizabethan maker of globes, mathematical instruments and ordnance. His terrestrial and celestial globes, first published in 1592, were the first to be made in England and the first to be made by an Englishman.

Molyneux was known as a mathematician and maker of mathematical instruments such as compasses and hourglasses. He became acquainted with many prominent men of the day, including the writer Richard Hakluyt and the mathematicians Robert Hues and Edward Wright. He also knew the explorers Thomas Cavendish, Francis Drake, Walter Raleigh and John Davis. Davis probably introduced Molyneux to his own patron, the London merchant William Sanderson, who largely financed the construction of the globes. When completed, the globes were presented to Elizabeth I. Larger globes were acquired by royalty, noblemen and academic institutions, while smaller ones were purchased as practical navigation aids for sailors and students. The globes were the first to be made in such a way that they were unaffected by the humidity at sea, and they came into general use on ships. (Full article...)

For thousands of years, mathematicians have attempted to extend their understanding of π, sometimes by computing its value to a high degree of accuracy. Ancient civilizations, including the Egyptians and Babylonians, required fairly accurate approximations of π for practical computations. Around 250 BC, the Greek mathematician Archimedes created an algorithm to approximate π with arbitrary accuracy. In the 5th century AD, Chinese mathematicians approximated π to seven digits, while Indian mathematicians made a five-digit approximation, both using geometrical techniques. The first computational formula for π, based on infinite series, was discovered a millennium later. The earliest known use of the Greek letter π to represent the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter was by the Welsh mathematician William Jones in 1706. (Full article...)

Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Philipp Cantor (/ˈkæntɔːr/ KAN-tor; German: [ˈɡeːɔʁk ˈfɛʁdinant ˈluːtvɪç ˈfiːlɪp ˈkantoːɐ̯]; 3 March [O.S. 19 February] 1845 – 6 January 1918) was a mathematician who played a pivotal role in the creation of set theory, which has become a fundamental theory in mathematics. Cantor established the importance of one-to-one correspondence between the members of two sets, defined infinite and well-ordered sets, and proved that the real numbers are more numerous than the natural numbers. Cantor's method of proof of this theorem implies the existence of an infinity of infinities. He defined the cardinal and ordinal numbers and their arithmetic. Cantor's work is of great philosophical interest, a fact he was well aware of.

Originally, Cantor's theory of transfinite numbers was regarded as counter-intuitive – even shocking. This caused it to encounter resistance from mathematical contemporaries such as Leopold Kronecker and Henri Poincaré and later from Hermann Weyl and L. E. J. Brouwer, while Ludwig Wittgenstein raised philosophical objections; see Controversy over Cantor's theory. Cantor, a devout Lutheran Christian, believed the theory had been communicated to him by God. Some Christian theologians (particularly neo-Scholastics) saw Cantor's work as a challenge to the uniqueness of the absolute infinity in the nature of God – on one occasion equating the theory of transfinite numbers with pantheism – a proposition that Cantor vigorously rejected. Not all theologians were against Cantor's theory; prominent neo-scholastic philosopher Constantin Gutberlet was in favor of it and Cardinal Johann Baptist Franzelin accepted it as a valid theory (after Cantor made some important clarifications). (Full article...)

Newton's law of universal gravitation, which describes classical gravity, can be seen as a prediction of general relativity for the almost flat spacetime geometry around stationary mass distributions. Some predictions of general relativity, however, are beyond Newton's law of universal gravitation in classical physics. These predictions concern the passage of time, the geometry of space, the motion of bodies in free fall, and the propagation of light, and include gravitational time dilation, gravitational lensing, the gravitational redshift of light, the Shapiro time delay and singularities/black holes. So far, all tests of general relativity have been shown to be in agreement with the theory. The time-dependent solutions of general relativity enable us to talk about the history of the universe and have provided the modern framework for cosmology, thus leading to the discovery of the Big Bang and cosmic microwave background radiation. Despite the introduction of a number of alternative theories, general relativity continues to be the simplest theory consistent with experimental data. (Full article...)

An actuary is a professional with advanced mathematical skills who deals with the measurement and management of risk and uncertainty. These risks can affect both sides of the balance sheet and require asset management, liability management, and valuation skills. Actuaries provide assessments of financial security systems, with a focus on their complexity, their mathematics, and their mechanisms. The name of the corresponding academic discipline is actuarial science.

While the concept of insurance dates to antiquity, the concepts needed to scientifically measure and mitigate risks have their origins in the 17th century studies of probability and annuities. Actuaries of the 21st century require analytical skills, business knowledge, and an understanding of human behavior and information systems to design programs that manage risk, by determining if the implementation of strategies proposed for mitigating potential risks, does not exceed the expected cost of those risks actualized. The steps needed to become an actuary, including education and licensing, are specific to a given country, with various additional requirements applied by regional administrative units; however, almost all processes impart universal principles of risk assessment, statistical analysis, and risk mitigation, involving rigorously structured training and examination schedules, taking many years to complete. (Full article...)

In mathematics, a group is a set with an operation that associates an element of the set to every pair of elements of the set (as does every binary operation) and satisfies the following constraints: the operation is associative, it has an identity element, and every element of the set has an inverse element.

Many mathematical structures are groups endowed with other properties. For example, the integers with the addition operation form an infinite group, which is generated by a single element called (these properties characterize the integers in a unique way). (Full article...)

The affine symmetric groups are a family of mathematical structures that describe the symmetries of the number line and the regular triangular tiling of the plane, as well as related higher-dimensional objects. In addition to this geometric description, the affine symmetric groups may be defined in other ways: as collections of permutations (rearrangements) of the integers (..., −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, ...) that are periodic in a certain sense, or in purely algebraic terms as a group with certain generators and relations. They are studied in combinatorics and representation theory.

A finite symmetric group consists of all permutations of a finite set. Each affine symmetric group is an infinite extension of a finite symmetric group. Many important combinatorial properties of the finite symmetric groups can be extended to the corresponding affine symmetric groups. Permutation statistics such as descents and inversions can be defined in the affine case. As in the finite case, the natural combinatorial definitions for these statistics also have a geometric interpretation. (Full article...)

Josiah Willard Gibbs (/ɡɪbz/; February 11, 1839 – April 28, 1903) was an American scientist who made significant theoretical contributions to physics, chemistry, and mathematics. His work on the applications of thermodynamics was instrumental in transforming physical chemistry into a rigorous deductive science. Together with James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann, he created statistical mechanics (a term that he coined), explaining the laws of thermodynamics as consequences of the statistical properties of ensembles of the possible states of a physical system composed of many particles. Gibbs also worked on the application of Maxwell's equations to problems in physical optics. As a mathematician, he created modern vector calculus (independently of the British scientist Oliver Heaviside, who carried out similar work during the same period) and described the Gibbs phenomenon in the theory of Fourier analysis.

In 1863, Yale University awarded Gibbs the first American doctorate in engineering. After a three-year sojourn in Europe, Gibbs spent the rest of his career at Yale, where he was a professor of mathematical physics from 1871 until his death in 1903. Working in relative isolation, he became the earliest theoretical scientist in the United States to earn an international reputation and was praised by Albert Einstein as "the greatest mind in American history". In 1901, Gibbs received what was then considered the highest honor awarded by the international scientific community, the Copley Medal of the Royal Society of London, "for his contributions to mathematical physics". (Full article...)

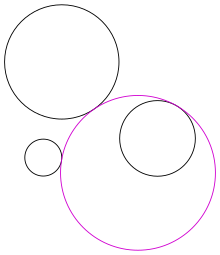

In Euclidean plane geometry, Apollonius's problem is to construct circles that are tangent to three given circles in a plane (Figure 1). Apollonius of Perga (c. 262 BC – c. 190 BC) posed and solved this famous problem in his work Ἐπαφαί (Epaphaí, "Tangencies"); this work has been lost, but a 4th-century AD report of his results by Pappus of Alexandria has survived. Three given circles generically have eight different circles that are tangent to them (Figure 2), a pair of solutions for each way to divide the three given circles in two subsets (there are 4 ways to divide a set of cardinality 3 in 2 parts).

In the 16th century, Adriaan van Roomen solved the problem using intersecting hyperbolas, but this solution does not use only straightedge and compass constructions. François Viète found such a solution by exploiting limiting cases: any of the three given circles can be shrunk to zero radius (a point) or expanded to infinite radius (a line). Viète's approach, which uses simpler limiting cases to solve more complicated ones, is considered a plausible reconstruction of Apollonius' method. The method of van Roomen was simplified by Isaac Newton, who showed that Apollonius' problem is equivalent to finding a position from the differences of its distances to three known points. This has applications in navigation and positioning systems such as LORAN. (Full article...)

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure of arguments alone, independent of their topic and content. Informal logic is associated with informal fallacies, critical thinking, and argumentation theory. Informal logic examines arguments expressed in natural language whereas formal logic uses formal language. When used as a countable noun, the term "a logic" refers to a specific logical formal system that articulates a proof system. Logic plays a central role in many fields, such as philosophy, mathematics, computer science, and linguistics.

Logic studies arguments, which consist of a set of premises that leads to a conclusion. An example is the argument from the premises "it's Sunday" and "if it's Sunday then I don't have to work" leading to the conclusion "I don't have to work". Premises and conclusions express propositions or claims that can be true or false. An important feature of propositions is their internal structure. For example, complex propositions are made up of simpler propositions linked by logical vocabulary like (and) or (if...then). Simple propositions also have parts, like "Sunday" or "work" in the example. The truth of a proposition usually depends on the meanings of all of its parts. However, this is not the case for logically true propositions. They are true only because of their logical structure independent of the specific meanings of the individual parts. (Full article...)

Selected image –

Good articles –

In statistics, maximum spacing estimation (MSE or MSP), or maximum product of spacing estimation (MPS), is a method for estimating the parameters of a univariate statistical model. The method requires maximization of the geometric mean of spacings in the data, which are the differences between the values of the cumulative distribution function at neighbouring data points.

The concept underlying the method is based on the probability integral transform, in that a set of independent random samples derived from any random variable should on average be uniformly distributed with respect to the cumulative distribution function of the random variable. The MPS method chooses the parameter values that make the observed data as uniform as possible, according to a specific quantitative measure of uniformity. (Full article...)

In mathematical logic and philosophy, Skolem's paradox is the apparent contradiction that a countable model of first-order set theory could contain an uncountable set. The paradox arises from part of the Löwenheim–Skolem theorem; Thoralf Skolem was the first to discuss the seemingly contradictory aspects of the theorem, and to discover the relativity of set-theoretic notions now known as non-absoluteness. Although it is not an actual antinomy like Russell's paradox, the result is typically called a paradox and was described as a "paradoxical state of affairs" by Skolem.

In model theory, a model corresponds to a specific interpretation of a formal language or theory. It consists of a domain (a set of objects) and an interpretation of the symbols and formulas in the language, such that the axioms of the theory are satisfied within this structure. The Löwenheim–Skolem theorem shows that any model of set theory in first-order logic, if it is consistent, has an equivalent model that is countable. This appears contradictory, because Georg Cantor proved that there exist sets which are not countable. Thus the seeming contradiction is that a model that is itself countable, and which therefore contains only countable sets, satisfies the first-order sentence that intuitively states "there are uncountable sets". (Full article...)

Sir Edmund Taylor Whittaker FRS FRSE (24 October 1873 – 24 March 1956) was a British mathematician, physicist, and historian of science. Whittaker was a leading mathematical scholar of the early 20th century who contributed widely to applied mathematics and was renowned for his research in mathematical physics and numerical analysis, including the theory of special functions, along with his contributions to astronomy, celestial mechanics, the history of physics, and digital signal processing.

Among the most influential publications in Whittaker's bibliography, he authored several popular reference works in mathematics, physics, and the history of science, including A Course of Modern Analysis (better known as Whittaker and Watson), Analytical Dynamics of Particles and Rigid Bodies, and A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity. Whittaker is also remembered for his role in the relativity priority dispute, as he credited Henri Poincaré and Hendrik Lorentz with developing special relativity in the second volume of his History, a dispute which has lasted several decades, though scientific consensus has remained with Einstein. Whittaker served as the Royal Astronomer of Ireland early in his career, a position he held from 1906 through 1912, before moving on to the chair of mathematics at the University of Edinburgh for the next three decades and, towards the end of his career, received the Copley Medal and was knighted. The School of Mathematics of the University of Edinburgh holds The Whittaker Colloquium, a yearly lecture, in his honour and the Edinburgh Mathematical Society promotes an outstanding young Scottish mathematician once every four years with the Sir Edmund Whittaker Memorial Prize, also given in his honour. (Full article...)

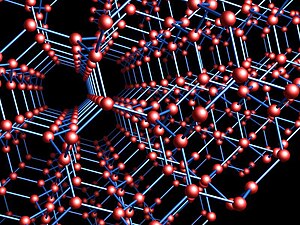

In geometry and crystallography, the Laves graph is an infinite and highly symmetric system of points and line segments in three-dimensional Euclidean space, forming a periodic graph. Three equal-length segments meet at 120° angles at each point, and all cycles use ten or more segments. It is the shortest possible triply periodic graph, relative to the volume of its fundamental domain. One arrangement of the Laves graph uses one out of every eight of the points in the integer lattice as its points, and connects all pairs of these points that are nearest neighbors, at distance . It can also be defined, divorced from its geometry, as an abstract undirected graph, a covering graph of the complete graph on four vertices.

H. S. M. Coxeter (1955) named this graph after Fritz Laves, who first wrote about it as a crystal structure in 1932. It has also been called the K4 crystal, (10,3)-a network, diamond twin, triamond, and the srs net. The regions of space nearest each vertex of the graph are congruent 17-sided polyhedra that tile space. Its edges lie on diagonals of the regular skew polyhedron, a surface with six squares meeting at each integer point of space. (Full article...)

Did you know (auto-generated) –

- ... that despite a mathematical model deeming the ice cream bar flavour Goody Goody Gum Drops impossible, it was still created?

- ... that in 1940 Xu Ruiyun became the first Chinese woman to receive a PhD in mathematics?

- ... that mathematics professor Ari Nagel has fathered more than a hundred children?

- ... that Catechumen, a Christian first-person shooter, was funded only in the aftermath of the Columbine High School massacre?

- ... that Latvian-Soviet artist Karlis Johansons exhibited a skeletal tensegrity form of the Schönhardt polyhedron seven years before Erich Schönhardt's 1928 paper on its mathematics?

- ... that ten-sided gaming dice have kite-shaped faces?

- ... that in the aftermath of the American Civil War, the only Black-led organization providing teachers to formerly enslaved people was the African Civilization Society?

- ... that more than 60 scientific papers authored by mathematician Paul Erdős were published posthumously?

More did you know –

- ... that as the dimension of a hypersphere tends to infinity, its "volume" (content) tends to 0?

- ...that the primality of a number can be determined using only a single division using Wilson's Theorem?

- ...that the line separating the numerator and denominator of a fraction is called a solidus if written as a diagonal line or a vinculum if written as a horizontal line?

- ...that a monkey hitting keys at random on a typewriter keyboard for an infinite amount of time will almost surely type the complete works of William Shakespeare?

- ... that there are 115,200 solutions to the ménage problem of permuting six female-male couples at a twelve-person table so that men and women alternate and are seated away from their partners?

- ... that mathematician Paul Erdős called the Hadwiger conjecture, a still-open generalization of the four-color problem, "one of the deepest unsolved problems in graph theory"?

- ...that the six permutations of the vector (1,2,3) form a regular hexagon in 3d space, the 24 permutations of (1,2,3,4) form a truncated octahedron in four dimensions, and both are examples of permutohedra?

Selected article –

|

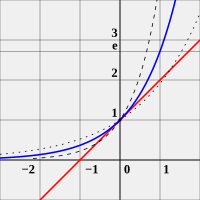

| e is the unique number such that the slope of y=e (blue curve) is exactly 1 when x=0 (illustrated by the red tangent line). For comparison, the curves y=2 (dotted curve) and y=4 (dashed curve) are shown. Image credit: Dick Lyon |

The mathematical constant e is occasionally called Euler's number after the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler, or Napier's constant in honor of the Scottish mathematician John Napier who introduced logarithms. It is one of the most important numbers in mathematics, alongside the additive and multiplicative identities 0 and 1, the imaginary unit i, and π, the circumference to diameter ratio for any circle. It has a number of equivalent definitions. One is given in the caption of the image to the right, and three more are:

- The sum of the infinite series

- where n! is the factorial of n, and 0! is defined to be 1 by convention.

- The global maximizer of the function

- The limit:

-

The number e is also the base of the natural logarithm. Since e is transcendental, and therefore irrational, its value can not be given exactly. The numerical value of e truncated to 20 decimal places is 2.71828 18284 59045 23536. (Full article...)

| View all selected articles |

Subcategories

Algebra | Arithmetic | Analysis | Complex analysis | Applied mathematics | Calculus | Category theory | Chaos theory | Combinatorics | Dynamical systems | Fractals | Game theory | Geometry | Algebraic geometry | Graph theory | Group theory | Linear algebra | Mathematical logic | Model theory | Multi-dimensional geometry | Number theory | Numerical analysis | Optimization | Order theory | Probability and statistics | Set theory | Statistics | Topology | Algebraic topology | Trigonometry | Linear programming

Mathematics | History of mathematics | Mathematicians | Awards | Education | Literature | Notation | Organizations | Theorems | Proofs | Unsolved problems

Topics in mathematics

| General | Foundations | Number theory | Discrete mathematics |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Algebra | Analysis | Geometry and topology | Applied mathematics |

Index of mathematics articles

| ARTICLE INDEX: | |

| MATHEMATICIANS: |

Related portals

WikiProjects

![]() The Mathematics WikiProject is the center for mathematics-related editing on Wikipedia. Join the discussion on the project's talk page.

The Mathematics WikiProject is the center for mathematics-related editing on Wikipedia. Join the discussion on the project's talk page.

In other Wikimedia projects

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus