Suleyman The Magnificent

After succeeding his father Selim I on 30 September 1520, Suleiman began his reign by launching military campaigns against the Christian powers of Central and Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean; Belgrade fell to him in 1521 and Rhodes in 1522–1523, and at Mohács in 1526, Suleiman broke the strength of the Kingdom of Hungary.

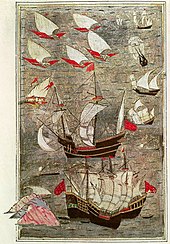

Presiding over the apex of the Ottoman Empire's economic, military, and political strength, Suleiman rose to become a prominent monarch of 16th-century Europe, as he personally led Ottoman armies in their conquests of a number of European Christian strongholds before his advances were finally checked at the siege of Vienna in 1529. On the front against the Safavids, his efforts enabled the Ottomans to annex much of the Middle East, in addition to large areas of North Africa as far west as modern-day Algeria. Simultaneously, the Ottoman fleet dominated the seas from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea and through the Persian Gulf.

At the helm of the rapidly expanding Ottoman Empire, Suleiman personally instituted major judicial changes relating to society, education, taxation, and criminal law. His reforms, carried out in conjunction with the Ottoman chief judicial official Ebussuud Efendi, harmonized the relationship between the two forms of Ottoman law: sultanic (Kanun) and Islamic (Sharia). He was a distinguished poet and goldsmith; he also became a great patron of fine culture, overseeing the "Golden Age" of the Ottoman Empire in its artistic, literary, and architectural development.

In 1533, Suleiman broke with Ottoman tradition by marrying Roxelana (Ukrainian: Роксолана), a woman from his Imperial Harem. Roxelana, so named in Western Europe for her red hair, was a Ruthenian who converted to Sunni Islam from Eastern Orthodox Chrisitianity and thereafter became one of the most influential figures of the "Sultanate of Women" period in the Ottoman Empire. Upon Suleiman's death in 1566, which ended his 46-year-long reign, he was succeeded by his and Roxelana's son Selim II. Suleiman's other potential heirs, Mehmed and Mustafa, had died; Mehmed had succumbed to smallpox in 1543, while Mustafa had been executed via strangling on Suleiman's orders in 1553. His other son Bayezid was also executed on his orders, along with Bayezid's four sons, after a rebellion in 1561. Although scholars typically regarded the period after his death to be one of crisis and adaptation rather than of simple decline, the end of Suleiman's reign was a watershed in Ottoman history. In the decades after Suleiman, the Ottoman Empire began to experience significant political, institutional, and economic changes—a phenomenon often referred to as the Era of Transformation.

Alternative names and titles

Suleiman the Magnificent (محتشم سليمان Muḥteşem Süleymān), as he was known in the West, was also called Suleiman the First (سلطان سليمان أول Sulṭān Süleymān-ı Evvel), and Suleiman the Lawgiver (قانونی سلطان سليمان Ḳānūnī Sulṭān Süleymān) for his reform of the Ottoman legal system.

It is unclear when exactly the term Kanunî (the Lawgiver) first came to be used as an epithet for Suleiman. It is entirely absent from sixteenth and seventeenth-century Ottoman sources and may date from the early 18th century.

There is a tradition of Western origin, according to which Suleiman the Magnificent was "Suleiman II", but that tradition has been based on an erroneous assumption that Süleyman Çelebi was to be recognised as a legitimate sultan.

Early life

Suleiman was born in Trabzon on the southern coast of the Black Sea to Şehzade Selim (later Selim I), probably on 6 November 1494, although this date is not known with absolute certainty or evidence. His mother was Hafsa Sultan, a concubine convert to Islam of unknown origins, who died in 1534. At the age of seven, Suleiman began studies of science, history, literature, theology and military tactics in the schools of the imperial Topkapı Palace in Constantinople. As a young man, he befriended Pargalı Ibrahim, a Greek slave who later became one of his most trusted advisers (but who was later executed on Suleiman's orders). At age seventeen, he was appointed as the governor of first Kaffa (Theodosia), then Manisa, with a brief tenure at Edirne.

Accession

Upon the death of his father, Selim I (r. 1512–1520), Suleiman entered Constantinople and ascended to the throne as the tenth Ottoman Sultan. An early description of Suleiman, a few weeks following his accession, was provided by the Venetian envoy Bartolomeo Contarini:

The sultan is only twenty-five years [actually 26] old, tall and slender but tough, with a thin and bony face. Facial hair is evident, but only barely. The sultan appears friendly and in good humor. Rumor has it that Suleiman is aptly named, enjoys reading, is knowledgeable and shows good judgment."

Military campaigns

Conquests in Europe

Upon succeeding his father, Suleiman began a series of military conquests, eventually leading to a revolt led by the Ottoman-appointed governor of Damascus in 1521. Suleiman soon made preparations for the conquest of Belgrade from the Kingdom of Hungary—something his great-grandfather Mehmed II had failed to achieve because of John Hunyadi's strong defense in the region. Its capture was vital in removing the Hungarians and Croats who, following the defeats of the Albanians, Bosniaks, Bulgarians, Byzantines and the Serbs, remained the only formidable force who could block further Ottoman gains in Europe. Suleiman encircled Belgrade and began a series of heavy bombardments from an island in the Danube. Belgrade, with a garrison of only 700 men, and receiving no aid from Hungary, fell in August 1521.

The road to Hungary and Austria lay open, but Suleiman turned his attention instead to the Eastern Mediterranean island of Rhodes, the home base of the Knights Hospitaller. Suleiman built a large fortification, Marmaris Castle, that served as a base for the Ottoman Navy. Following a five-month siege, Rhodes capitulated and Suleiman allowed the Knights of Rhodes to depart. The conquest of the island cost the Ottomans 50,000 to 60,000 dead from battle and sickness (Christian claims went as high as 64,000 Ottoman battle deaths and 50,000 disease deaths).

As relations between Hungary and the Ottoman Empire deteriorated, Suleiman resumed his campaign in Central Europe, and on 29 August 1526 he defeated Louis II of Hungary (1506–1526) at the Battle of Mohács. Upon encountering the lifeless body of King Louis, Suleiman is said to have lamented: "I came indeed in arms against him; but it was not my wish that he should be thus cut off before he scarcely tasted the sweets of life and royalty." While Suleiman was campaigning in Hungary, Turkmen tribes in central Anatolia (in Cilicia) revolted under the leadership of Kalender Çelebi.

Some Hungarian nobles proposed that Ferdinand, who was the ruler of neighboring Austria and tied to Louis II's family by marriage, be King of Hungary, citing previous agreements that the Habsburgs would take the Hungarian throne if Louis died without heirs. However, other nobles turned to the nobleman John Zápolya, whom Suleiman supported. Under Charles V and his brother Ferdinand I, the Habsburgs reoccupied Buda and took possession of Hungary. Reacting in 1529, Suleiman marched through the valley of the Danube and regained control of Buda; in the following autumn, his forces laid siege to Vienna. This was to be the Ottoman Empire's most ambitious expedition and the apogee of its drive to the West. With a reinforced garrison of 16,000 men, the Austrians inflicted the first defeat on Suleiman, sowing the seeds of a bitter Ottoman–Habsburg rivalry that lasted until the 20th century. His second attempt to conquer Vienna failed in 1532, as Ottoman forces were delayed by the siege of Güns and failed to reach Vienna. In both cases, the Ottoman army was plagued by bad weather, forcing them to leave behind essential siege equipment, and was hobbled by overstretched supply lines. In 1533 the Treaty of Constantinople was signed by Ferdinand I, in which he acknowledged Ottoman suzerainty and recognised Suleiman as his "father and suzerain", he also agreed to pay an annual tribute and accepted the Ottoman grand vizier as his brother and equal in rank.

By the 1540s, a renewal of the conflict in Hungary presented Suleiman with the opportunity to avenge the defeat suffered at Vienna. In 1541, the Habsburgs attempted to lay siege to Buda but were repulsed, and more Habsburg fortresses were captured by the Ottomans in two consecutive campaigns in 1541 and 1544 as a result, Ferdinand and Charles were forced to conclude a humiliating five-year treaty with Suleiman. Ferdinand renounced his claim to the Kingdom of Hungary and was forced to pay a fixed yearly sum to the Sultan for the Hungarian lands he continued to control. Of more symbolic importance, the treaty referred to Charles V not as "Emperor" but as the "King of Spain", leading Suleiman to identify as the true "Caesar".

In 1552, Suleiman's forces laid siege to Eger, located in the northern part of the Kingdom of Hungary, but the defenders led by István Dobó repelled the attacks and defended the Eger Castle.

Ottoman–Safavid War

Suleiman's father had made war with Persia a high priority. At first, Suleiman shifted attention to Europe and was content to contain Persia, which was preoccupied by its own enemies to its east. After Suleiman stabilized his European frontiers, he now turned his attention to Persia, the base for the rival Shia Muslim faction. The Safavid dynasty became the main enemy after two episodes. First, Shah Tahmasp killed the Baghdad governor loyal to Suleiman, and put his own man in. Second, the governor of Bitlis had defected and sworn allegiance to the Safavids. As a result, in 1533, Suleiman ordered his Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha to lead an army into eastern Asia Minor where he retook Bitlis and occupied Tabriz without resistance. Suleiman joined Ibrahim in 1534. They made a push towards Persia, only to find the Shah sacrificing territory instead of facing a pitched battle, resorting to harassment of the Ottoman army as it proceeded along the harsh interior. In 1535 Suleiman made a grand entrance into Baghdad. He enhanced his local support by restoring the tomb of Abu Hanifa, the founder of the Hanafi school of Islamic law to which the Ottomans adhered.

Attempting to defeat the Shah once and for all, Suleiman embarked upon a second campaign in 1548–1549. As in the previous attempt, Tahmasp avoided confrontation with the Ottoman army and instead chose to retreat, using scorched earth tactics in the process and exposing the Ottoman army to the harsh winter of the Caucasus. Suleiman abandoned the campaign with temporary Ottoman gains in Tabriz and the Urmia region, a lasting presence in the province of Van, control of the western half of Azerbaijan and some forts in Georgia.

In 1553, Suleiman began his third and final campaign against the Shah. Having initially lost territories in Erzurum to the Shah's son, Suleiman retaliated by recapturing Erzurum, crossing the Upper Euphrates and laying waste to parts of Persia. The Shah's army continued its strategy of avoiding the Ottomans, leading to a stalemate from which neither army made any significant gain. In 1555, a settlement known as the Peace of Amasya was signed, which defined the borders of the two empires. By this treaty, Armenia and Georgia were divided equally between the two, with Western Armenia, western Kurdistan, and western Georgia (incl. western Samtskhe) falling in Ottoman hands while Eastern Armenia, eastern Kurdistan, and eastern Georgia (incl. eastern Samtskhe) stayed in Safavid hands. The Ottoman Empire obtained most of Iraq, including Baghdad, which gave them access to the Persian Gulf, while the Persians retained their former capital Tabriz and all their other northwestern territories in the Caucasus and as they were prior to the wars, such as Dagestan and all of what is now Azerbaijan.

Campaigns in the Indian Ocean

Ottoman ships had been sailing in the Indian Ocean since the year 1518. Ottoman admirals such as Hadim Suleiman Pasha, Seydi Ali Reis and Kurtoğlu Hızır Reis are known to have voyaged to the Mughal imperial ports of Thatta, Surat and Janjira. The Mughal Emperor Akbar the Great himself is known to have exchanged six documents with Suleiman the Magnificent.

Suleiman led several naval campaigns against the Portuguese in an attempt to remove them and reestablish trade with the Mughal Empire. Aden in Yemen was captured by the Ottomans in 1538, in order to provide an Ottoman base for raids against Portuguese possessions on the western coast of the Mughal Empire. Sailing on, the Ottomans failed against the Portuguese at the siege of Diu in September 1538, but then returned to Aden, where they fortified the city with 100 pieces of artillery. From this base, Sulayman Pasha managed to take control of the whole country of Yemen, also taking Sana'a.

With its strong control of the Red Sea, Suleiman successfully managed to dispute control of the trade routes to the Portuguese and maintained a significant level of trade with the Mughal Empire throughout the 16th century.

From 1526 until 1543, Suleiman stationed over 900 Turkish soldiers to fight alongside the Somali Adal Sultanate led by Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi during the Conquest of Abyssinia. After the first Ajuran-Portuguese war, the Ottoman Empire would in 1559 absorb the weakened Adal Sultanate into its domain. This expansion furthered Ottoman rule in Somalia and the Horn of Africa. This also increased its influence in the Indian Ocean to compete with the Portuguese Empire with its close ally, the Ajuran Empire.

In 1564, Suleiman received an embassy from Aceh (a sultanate on Sumatra, in modern Indonesia), requesting Ottoman support against the Portuguese. As a result, an Ottoman expedition to Aceh was launched, which was able to provide extensive military support to the Acehnese.

The discovery of new maritime trade routes by Western European states allowed them to avoid the Ottoman trade monopoly. The Portuguese discovery of the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 initiated a series of Ottoman-Portuguese naval wars in the Ocean throughout the 16th century. The Ajuran Sultanate allied with the Ottomans defied the Portuguese economic monopoly in the Indian Ocean by employing a new coinage which followed the Ottoman pattern, thus proclaiming an attitude of economic independence in regard to the Portuguese.

Mediterranean and North Africa

Having consolidated his conquests on land, Suleiman was greeted with the news that the fortress of Koroni in Morea (the modern Peloponnese, peninsular Greece) had been lost to Charles V's admiral, Andrea Doria. The presence of the Spanish in the Eastern Mediterranean concerned Suleiman, who saw it as an early indication of Charles V's intention to rival Ottoman dominance in the region. Recognizing the need to reassert naval preeminence in the Mediterranean, Suleiman appointed an exceptional naval commander in the form of Khair ad Din, known to Europeans as Barbarossa. Once appointed admiral-in-chief, Barbarossa was charged with rebuilding the Ottoman fleet.

In 1535, Charles V led a Holy League of 26,700 soldiers (10,000 Spaniards, 8,000 Italians, 8,000 Germans, and 700 Knights of St. John) to victory against the Ottomans at Tunis, which together with the war against Venice the following year, led Suleiman to accept proposals from Francis I of France to form an alliance against Charles. Huge Muslim territories in North Africa were annexed. The piracy carried on thereafter by the Barbary pirates of North Africa can be seen in the context of the wars against Spain.

In 1541, the Spaniards led an unsuccessful expedition to Algiers. In 1542, facing a common Habsburg enemy during the Italian Wars, Francis I sought to renew the Franco-Ottoman alliance. In early 1542, Polin successfully negotiated the details of the alliance, with the Ottoman Empire promising to send 60,000 troops against the territories of the German king Ferdinand, as well as 150 galleys against Charles, while France promised to attack Flanders, harass the coasts of Spain with a naval force, and send 40 galleys to assist the Turks for operations in the Levant.

In August 1551, Ottoman naval commander Turgut Reis attacked and captured Tripoli, which had been a possession of the Knights of Malta since 1530. In 1553, Turgut Reis was nominated commander of Tripoli by Suleiman, making the city an important center for piratical raids in the Mediterranean and the capital of the Ottoman province of Tripolitania. In 1560, a powerful naval force was sent to recapture Tripoli, but that force was defeated in the Battle of Djerba.

Elsewhere in the Mediterranean, when the Knights Hospitallers were re-established as the Knights of Malta in 1530, their actions against Muslim navies quickly drew the ire of the Ottomans, who assembled another massive army in order to dislodge the Knights from Malta. The Ottomans invaded Malta in 1565, undertaking the Great Siege of Malta, which began on 18 May and lasted until 8 September, and is portrayed vividly in the frescoes of Matteo Perez d'Aleccio in the Hall of St. Michael and St. George. At first, it seemed that this would be a repeat of the battle on Rhodes, with most of Malta's cities destroyed and half the Knights killed in battle; but a relief force from Spain entered the battle, resulting in the loss of 10,000 Ottoman troops and the victory of the local Maltese citizenry.

Legal and political reforms

While Sultan Suleiman was known as "the Magnificent" in the West, he was always Kanuni Suleiman or "The Lawgiver" (قانونی) to his Ottoman subjects. The overriding law of the empire was the Shari'ah, or Sacred Law, which as the divine law of Islam was outside of the Sultan's powers to change. Yet an area of distinct law known as the Kanuns (قانون, canonical legislation) was dependent on Suleiman's will alone, covering areas such as criminal law, land tenure and taxation. He collected all the judgments that had been issued by the nine Ottoman Sultans who preceded him. After eliminating duplications and choosing between contradictory statements, he issued a single legal code, all the while being careful not to violate the basic laws of Islam. It was within this framework that Suleiman, supported by his Grand Mufti Ebussuud, sought to reform the legislation to adapt to a rapidly changing empire. When the Kanun laws attained their final form, the code of laws became known as the kanun‐i Osmani (قانون عثمانی), or the "Ottoman laws". Suleiman's legal code was to last more than three hundred years.

The Sultan also played a role in protecting the Jewish subjects of his empire for centuries to come. In late 1553 or 1554, on the suggestion of his favorite doctor and dentist, the Spanish Jew Moses Hamon, the Sultan issued a firman (فرمان) formally denouncing blood libels against the Jews. Furthermore, Suleiman enacted new criminal and police legislation, prescribing a set of fines for specific offenses, as well as reducing the instances requiring death or mutilation. In the area of taxation, taxes were levied on various goods and produce, including animals, mines, profits of trade, and import-export duties.

Higher medreses provided education of university status, whose graduates became imams (امام) or teachers. Educational centers were often one of many buildings surrounding the courtyards of mosques, others included libraries, baths, soup kitchens, residences and hospitals for the benefit of the public.

The arts under Suleiman

Under Suleiman's patronage, the Ottoman Empire entered the golden age of its cultural development. Hundreds of imperial artistic societies (called the اهل حرف Ehl-i Hiref, "Community of the Craftsmen") were administered at the Imperial seat, the Topkapı Palace. After an apprenticeship, artists and craftsmen could advance in rank within their field and were paid commensurate wages in quarterly annual installments. Payroll registers that survive testify to the breadth of Suleiman's patronage of the arts, the earliest of the documents dating from 1526 list 40 societies with over 600 members. The Ehl-i Hiref attracted the empire's most talented artisans to the Sultan's court, both from the Islamic world and from the recently conquered territories in Europe, resulting in a blend of Arabic, Turkish and European cultures. Artisans in service of the court included painters, book binders, furriers, jewellers and goldsmiths. Whereas previous rulers had been influenced by Persian culture (Suleiman's father, Selim I, wrote poetry in Persian), Suleiman's patronage of the arts saw the Ottoman Empire assert its own artistic legacy.

Suleiman himself was an accomplished poet, writing in Persian and Turkish under the takhallus (nom de plume) Muhibbi (محبی, "Lover"). Some of Suleiman's verses have become Turkish proverbs, such as the well-known Everyone aims at the same meaning, but many are the versions of the story. When his young son Mehmed died in 1543, he composed a moving chronogram to commemorate the year: Peerless among princes, my Sultan Mehmed. In Turkish the chronogram reads شهزادهلر گزیدهسی سلطان محمدم (Şehzadeler güzidesi Sultan Muhammed'üm), in which the Arabic Abjad numerals total 955, the equivalent in the Islamic calendar of 1543 AD. In addition to Suleiman's own work, many great talents enlivened the literary world during Suleiman's rule, including Fuzûlî and Bâkî. The literary historian Elias John Wilkinson Gibb observed that "at no time, even in Turkey, was greater encouragement given to poetry than during the reign of this Sultan". Suleiman's most famous verse is:

The people think of wealth and power as the greatest fate,

But in this world a spell of health is the best state.

What men call sovereignty is a worldly strife and constant war;

Worship of God is the highest throne, the happiest of all estates.

Suleiman also became renowned for sponsoring a series of monumental architectural developments within his empire. The Sultan sought to turn Constantinople into the center of Islamic civilization by a series of projects, including bridges, mosques, palaces and various charitable and social establishments. The greatest of these were built by the Sultan's chief architect, Mimar Sinan, under whom Ottoman architecture reached its zenith. Sinan became responsible for over three hundred monuments throughout the empire, including his two masterpieces, the Süleymaniye and Selimiye mosques—the latter built in Adrianople (now Edirne) in the reign of Suleiman's son Selim II. Suleiman also restored the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Walls of Jerusalem (which are the current walls of the Old City of Jerusalem), renovated the Kaaba in Mecca, and constructed a complex in Damascus.

Tulips

Suleiman loved gardens and his shaykh grew a white tulip in one of the gardens. Some of the nobles in the court had seen the tulip and they also began growing their own. Soon images of the tulip were woven into rugs and fired into ceramics. Suleiman is credited with large-scale cultivation of the tulip and it is thought that the tulips spread throughout Europe because of Suleiman. It is thought that diplomats who visited him were gifted the flowers while visiting his court.

Suleiman's passion for tulips set a precedent for their cultivation and cultural significance in the Ottoman Empire. This fascination continued to flourish, reaching its zenith under Sultan Ahmet III, who ascended the throne in 1703. Ahmet III's gardens in Istanbul were adorned with tulips from Turkey's mountains and the finest bulbs imported from Dutch commercial growers. Throughout his reign, he imported millions of Dutch tulip bulbs, reflecting the enduring legacy of Suleiman's influence and the extravagant height of tulip culture during this period.

Personal life

Consorts

Suleiman had two known consorts:

- Mahidevran Hatun, a Circassian or Albanian or Montenegrin concubine, she entered in Süleyman's harem when he was prince in Manisa;

- Hürrem Sultan, known in West as Roxelana (m. 1533), Suleiman's only favorite concubine during his reign, and later legal wife and first Haseki sultan, possibly a daughter of a Ruthenian Orthodox priest.

Sons

Suleiman I had at least eight sons:

- Şehzade Mahmud (c. 1513, Manisa Palace, Manisa – 29 October 1520, Old Palace, Istanbul, and buried in Yavuz Selim Mosque);

- Şehzade Murad (c. 1515, Manisa Palace, Manisa – 19 October 1520, Old Palace, and Istanbul, buried in Yavuz Selim Mosque);

- Şehzade Mustafa (c.1516/1517, Manisa Palace, Manisa – executed, by the order of his father, 6 October 1553, Konya, buried in Muradiye Complex, Bursa), with Mahidevran;

- Şehzade Mehmed (1521, Old Palace, Istanbul – 6 November 1543, Manisa Palace, Manisa, buried in Şehzade Mosque, Istanbul), with Hürrem;

- Sultan Selim II (30 May 1524, Old Palace, Istanbul – 15 December 1574, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, buried in Selim II Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque), with Hürrem;

- Şehzade Abdullah (c. 1525, Old Palace, Istanbul – c. 1528, Old Palace, Istanbul, and buried in Yavuz Selim Mosque), with Hürrem;

- Şehzade Bayezid (1527, Old Palace, Istanbul – executed by agents of his father on 25 September 1561, Qazvin, Safavid Empire, buried in Melik-i Acem Türbe, Sivas), with Hürrem;

- Şehzade Cihangir (1531, Old Palace, Istanbul – 27 November 1553, Konya, buried in Şehzade Mosque, Istanbul), with Hürrem;

Daughters

Suleiman had two daughters:

- Raziye Sultan (c. 1519 – c. 1520, and buried in Yahya Efendi mausoleum);

- Mihrimah Sultan (1522, Old Palace, Istanbul – 25 January 1578, buried in Suleiman I Mausoleum, Süleymaniye Mosque), with Hürrem, married Rüstem Pasha in 1539;

Relationship with Hurrem Sultan

Suleiman fell in love with Hurrem Sultan, a harem girl from Ruthenia, then part of Poland. Western diplomats, taking notice of the palace gossip about her, called her "Russelazie" or "Roxelana", referring to her Ruthenian origins. The daughter of an Orthodox priest, she was captured by Tatars from Crimea, sold as a slave in Constantinople, and eventually rose through the ranks of the Harem to become Suleiman's favorite. Hurrem, a former concubine, became the legal wife of the Sultan, much to the astonishment of the observers in the palace and the city. He also allowed Hurrem Sultan to remain with him at court for the rest of her life, breaking another tradition—that when imperial heirs came of age, they would be sent along with the imperial concubine who bore them to govern remote provinces of the Empire, never to return unless their progeny succeeded to the throne.

Under his pen name, Muhibbi, Sultan Suleiman composed this poem for Hurrem Sultan:

Throne of my lonely niche, my wealth, my love, my moonlight.

My most sincere friend, my confidant, my very existence, my Sultan, my one and only love.

The most beautiful among the beautiful ...

My springtime, my merry faced love, my daytime, my sweetheart, laughing leaf ...

My plants, my sweet, my rose, the one only who does not distress me in this room ...

My Istanbul, my Karaman, the earth of my Anatolia

My Badakhshan, my Baghdad and Khorasan

My woman of the beautiful hair, my love of the slanted brow, my love of eyes full of misery ...

I'll sing your praises always

I, lover of the tormented heart, Muhibbi of the eyes full of tears, I am happy.

Grand Vizier Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha

Before his downfall, Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha was an inseparable friend and possible lover of Suleiman. In fact, he is referred to by his chroniclers as "the favourite" (Maḳbūl) along with "the executed" (Maḳtūl). Historians state that Suleiman I is remembered for "his passion for two of his slaves: for his beloved Ibrahim when the sultan was a hot-blooded youth, and for his beloved Hurrem when he was mature."

Ibrahim was originally a Christian from Parga (in Epirus), who was captured in a raid during the 1499–1503 Ottoman–Venetian War, and was given as a slave to Suleiman most likely in 1514. Ibrahim converted to Islam and Suleiman made him the royal falconer, then promoted him to first officer of the Royal Bedchamber. It was reported that they slept together in the same bed. The sultan also built Ibrahim a lavish palace on the ancient Hippodrome, Istanbul's main forum outside the Hagia Sophia and Topkapı Palace. Despite his following marriage and his new sumptuous residence, Ibrahim sometimes spent the night with Suleiman I at Topkapı Palace. In turn, the sultan occasionally slept at Ibrahim's lodgings. Ibrahim Pasha rose to Grand Vizier in 1523 and commander-in-chief of all the armies. Suleiman also conferred upon Ibrahim Pasha the honor of beylerbey of Rumelia (first-ranking military governor-general), granting Ibrahim authority over all Ottoman territories in Europe, as well as command of troops residing within them in times of war. At the time, Ibrahim was only about thirty years old and lacked any actual military expertise; it is said that 'tongues wagged' at this unprecedented promotion straight from palace service to the two highest offices of the empire.

During his thirteen years as Grand Vizier, his rapid rise to power and vast accumulation of wealth had made Ibrahim many enemies at the Sultan's court. Suleiman's suspicion of Ibrahim was worsened by a quarrel between the latter and the finance secretary (defterdar) İskender Çelebi. The dispute ended in the disgrace of Çelebi on charges of intrigue, with Ibrahim convincing Suleiman to sentence the defterdar to death. Ibrahim also supported Şehzade Mustafa as the successor of Suleiman. This caused disputes between him and Hurrem Sultan, who wanted her sons to succeed to the throne. Ibrahim eventually fell from grace with the Sultan and his wife. Suleiman consulted his Qadi, who suggested that Ibrahim be put to death. The Sultan recruited assassins and ordered them to strangle Ibrahim in his sleep.

Succession

Sultan Suleiman's two known consorts (Hurrem and Mahidevran) had borne him six sons, four of whom survived past the 1550s. They were Mustafa, Selim, Bayezid, and Cihangir. The eldest was Mahidevran's son, while Selim, Bayezid, and Cihangir were born to Hurrem. Hurrem is usually held at least partly responsible for the intrigues in nominating a successor, though there is no evidence to support this. Although she was Suleiman's wife, she exercised no official public role. This did not, however, prevent Hurrem from wielding powerful political influence. Until the reign of Ahmed I (1603–1617), the Empire had no formal means of nominating a successor, so successions usually involved the death of competing princes in order to avert civil unrest and rebellions.

By 1552, when the campaign against Persia had begun with Rüstem appointed commander-in-chief of the expedition, intrigues against Mustafa began. Rüstem sent one of Suleiman's most trusted men to report that since Suleiman was not at the head of the army, the soldiers thought the time had come to put a younger prince on the throne; at the same time, he spread rumours that Mustafa had proved receptive to the idea. Angered by what he came to believe were Mustafa's plans to claim the throne, the following summer upon return from his campaign in Persia, Suleiman summoned him to his tent in the Ereğli valley. When Mustafa entered his father's tent to meet with him, Suleiman's eunuchs attacked Mustafa, and after a long struggle the mutes killed him using a bow-string.

Cihangir is said to have died of grief a few months after the news of his half-brother's murder. The two surviving brothers, Selim and Bayezid, were given command in different parts of the empire. Within a few years, however, civil war broke out between the brothers, each supported by his loyal forces. With the aid of his father's army, Selim defeated Bayezid in Konya in 1559, leading the latter to seek refuge with the Safavids along with his four sons. Following diplomatic exchanges, the Sultan demanded from the Safavid Shah that Bayezid be either extradited or executed. In return for large amounts of gold, the Shah allowed a Turkish executioner to strangle Bayezid and his four sons in 1561, clearing the path for Selim's succession to the throne five years later.

Death

On 6 September 1566, Suleiman, who had set out from Constantinople to command an expedition to Hungary, died before an Ottoman victory at the siege of Szigetvár in Hungary at the age of 71 and his Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha kept his death secret during the retreat for the enthronement of Selim II. The sultan's body was taken back to Istanbul to be buried, while his heart, liver, and some other organs were buried in Turbék, outside Szigetvár. A mausoleum constructed above the burial site came to be regarded as a holy place and pilgrimage site. Within a decade a mosque and Sufi hospice were built near it, and the site was protected by a salaried garrison of several dozen men.

Legacy

The formation of Suleiman's legacy began even before his death. Throughout his reign literary works were commissioned praising Suleiman and constructing an image of him as an ideal ruler, most significantly by Celalzade Mustafa, chancellor of the empire from 1534 to 1557. Later Ottoman writers applied this idealised image of Suleiman to the Near Eastern literary genre of advice literature named naṣīḥatnāme, urging sultans to conform to his model of rulership and to maintain the empire's institutions in their sixteenth-century form. Such writers were pushing back against the political and institutional transformation of the empire after the middle of the sixteenth century, and portrayed deviation from the norm as it had existed under Suleiman as evidence of the decline of the empire. Western historians, failing to recognise that these 'decline writers' were working within an established literary genre and often had deeply personal reasons for criticizing the empire, long took their claims at face value and consequently adopted the idea that the empire entered a period of decline after the death of Suleiman. Since the 1980s this view has been thoroughly reexamined, and modern scholars have come to overwhelmingly reject the idea of decline, labelling it an "untrue myth".

Suleiman's conquests had brought under the control of the Empire major Muslim cities (such as Baghdad), many Balkan provinces (reaching present day Croatia and Hungary), and most of North Africa. His expansion into Europe had given the Ottoman Turks a powerful presence in the European balance of power. Indeed, such was the perceived threat of the Ottoman Empire under the reign of Suleiman that Austria's ambassador Busbecq warned of Europe's imminent conquest: "On [the Turks'] side are the resources of a mighty empire, strength unimpaired, habituation to victory, endurance of toil, unity, discipline, frugality and watchfulness ... Can we doubt what the result will be? ... When the Turks have settled with Persia, they will fly at our throats supported by the might of the whole East; how unprepared we are I dare not say." Suleiman's legacy was not, however, merely in the military field. The French traveler Jean de Thévenot bears witness a century later to the "strong agricultural base of the country, the well being of the peasantry, the abundance of staple foods and the pre-eminence of organization in Suleiman's government".

Even thirty years after his death, "Sultan Solyman" was quoted by the English playwright William Shakespeare as a military prodigy in The Merchant of Venice, where the Prince of Morocco boasts about his prowess by saying that he defeated Suleiman in three battles (Act 2, Scene 1).

Through the distribution of court patronage, Suleiman also presided over a golden age in Ottoman arts, witnessing immense achievement in the realms of architecture, literature, art, theology and philosophy. Today the skyline of the Bosphorus and of many cities in modern Turkey and the former Ottoman provinces, are still adorned with the architectural works of Mimar Sinan. One of these, the Süleymaniye Mosque, is the final resting place of Suleiman: he is buried in a domed mausoleum attached to the mosque.

Nevertheless, assessments of Suleiman's reign have frequently fallen into the trap of the Great Man theory of history. The administrative, cultural, and military achievements of the age were a product not of Suleiman alone, but also of the many talented figures who served him, such as grand viziers Ibrahim Pasha and Rüstem Pasha, the Grand Mufti Ebussuud Efendi, who played a major role in legal reform, and chancellor and chronicler Celalzade Mustafa, who played a major role in bureaucratic expansion and in constructing Suleiman's legacy.

In an inscription dating from 1537 on the citadel of Bender, Moldova, Suleiman the Magnificent gave expression to his power:

I am God's slave and sultan of this world. By the grace of God I am head of Muhammad's community. God's might and Muhammad's miracles are my companions. I am Süleymân, in whose name the hutbe is read in Mecca and Medina. In Baghdad I am the shah, in Byzantine realms the caesar, and in Egypt the sultan; who sends his fleets to the seas of Europe, the Maghrib and India. I am the sultan who took the crown and throne of Hungary and granted them to a humble slave. The voivoda Petru raised his head in revolt, but my horse's hoofs ground him into the dust, and I conquered the land of Moldovia.

Suleiman, as sculpted by Joseph Kiselewski, is present on one of the 23 relief portraits over the gallery doors of the House Chamber of the United States Capitol that depicts historical figures noted for their work in establishing the principles that underlie American law.

See also

Notes

- ^ Dimitri Korobeinikov (2021). "These are the narratives of bygone years: Conquest of a Fortress as a Source of Legitimacy". medieval worlds comparative & interdisciplinary studies (PDF). Vol. 14. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. p. 180.

That the Ottomans might have had a different view was demonstrated by Sultan Sulaymān the Magnificent, who called himself the shah of Baghdad in 'Iraq (Shah-i Bagdād-i 'Irāq), the Caesar of Rome (qayṣar-i Rūm), and the sultan in Egypt (Miṣra (i.e. Mısıra) Sulṭān) in the inscription in the fortress of Bender (Bendery, Tighina) in Moldova, AH 945 (29 May 1538–18 May 1539). The title qayṣar-i Rūm (Caesar of Rome) was a traditional designation of the Byzantine emperor in Persian and Ottoman sources (from the Arabic al-qayṣar al-Rūm).

- ^ Oriental Translation Fund. Vol. 33. 1834. p. 19.

- ^ Ágoston, Gábor (2009). "Süleyman I". In Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire.

- ^ Hüseyin Odabaş; Coşkun Odabaş (2015). Manuscript and Ferman Ornamentation Art in the Ottoman Empire. p. 123.

- ^ Mansel, Philip (1998). Constantinople: City of the World's Desire, 1453–1924.

- ^ Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300–1923. Basic Books. p. 145.

- ^ Atıl, Esin (July–August 1987). "The Golden Age of Ottoman Art". Saudi Aramco World. 38 (4). Houston, Texas: Aramco Services Co: 24–33. ISSN 1530-5821. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- ^ Hathaway, Jane (2008). The Arab Lands under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1800. Pearson Education Ltd. p. 8.

historians of the Ottoman Empire have rejected the narrative of decline in favor of one of crisis and adaptation

- ^ Tezcan, Baki (2010). The Second Ottoman Empire: Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern Period. Cambridge University Press. p. 9.

the conventional narrative of Ottoman history – that in the late sixteenth century the Ottoman Empire entered a prolonged period of decline marked by steadily increasing military decay and institutional corruption – has been discarded.

- ^ Woodhead, Christine (2011). "Introduction". In Woodhead, Christine (ed.). The Ottoman World. p. 5.

Ottomanist historians have largely jettisoned the notion of a post-1600 'decline'

- ^ Şahin, Kaya (2013). Empire and Power in the Reign of Süleyman: Narrating the Sixteenth-Century Ottoman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Tezcan, Baki (2010). The Second Ottoman Empire: Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern Period. Cambridge University Press. p. 10.

- ^ "Suleyman the Magnificent". Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford University Press. 2004.

- ^ Kafadar, Cemal (1993). "The Myth of the Golden Age: Ottoman Historical Consciousness in the Post-Süleymânic Era". In İnalcık, Halil; Cemal Kafadar (eds.). Süleyman the Second [i.e. the First] and His Time. Istanbul: The Isis Press. p. 41. ISBN 975-428-052-5.

- ^ Veinstein, G. "Süleymān". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 2.

- ^ Lowry, Heath (1993). "Süleymân's Formative Years in the City of Trabzon: Their Impact on the Future Sultan and the City". In İnalcık, Halil; Cemal Kafadar (eds.). Süleyman the Second [i.e. the First] and His Time. Istanbul: The Isis Press. p. 21. ISBN 975-428-052-5.

- ^ Fisher, Alan (1993). "The Life and Family of Süleymân I". In İnalcık, Halil; Kafadar, Cemal (eds.). Süleymân The Second [i.e. the First] and His Time. Istanbul: Isis Press. ISBN 9754280525.

- ^ Barber, Noel (1973). The Sultans. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 36. ISBN 0-7861-0682-4.

- ^ Imber, Colin (2002). The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650 : The Structure of Power. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-61386-3.

- ^ Bunting, Tony. "Siege of Rhodes". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Publishing, D. K. (2009). War: The Definitive Visual History. Penguin. ISBN 978-0756668174 – via Google Books.

- ^ Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (14th ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707 – via Google Books.

- ^ Severy, Merle (November 1987). "The World of Süleyman the Magnificent". National Geographic. 172 (5). Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society: 580. ISSN 0027-9358.

- ^ Ciachir, N. (1972). "Soliman Magnificul" [Soliman the Magnificent]. Editura enciclopedică română. Bucharest. p. 157.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2003). The Ottoman Empire 1326–1699. New York: Osprey Publishing. p. 50.

- ^ Labib, Subhi (November 1979). "The Era of Suleyman the Magnificent: Crisis of Orientation". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 10 (4). London: Cambridge University Press: 435–451. doi:10.1017/S002074380005128X. ISSN 0020-7438. S2CID 162249695.

- ^ Bonney, Richard. "Suleiman I ("the Magnificent") (1494–1566)." Archived 8 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine The Encyclopedia of War (2011).

- ^ Somel, Selcuk Aksin. The A to Z of the Ottoman Empire. No. 152. Archived 8 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine Rowman & Littlefield, 2010.

- ^ Erasmus, Desiderius. The Correspondence of Erasmus: Letters 2635 to 2802 April 1532–April 1533. Vol. 19. Archived 26 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine University of Toronto Press, 2019.

- ^ Shaw, Stanford J., and Ezel Kural Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume 1, Empire of the Gazis: The Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire 1280–1808. Vol. 1. Archived 8 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- ^ Faroqhi, Suraiya N., and Kate Fleet, eds. The Cambridge History of Turkey: Volume 2, The Ottoman Empire as a World Power, 1453–1603. Archived 8 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine Cambridge University Press, 2012

- ^ "István Dobó". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Sicker, Martin (2000). The Islamic World In Ascendancy : From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna. p. 206.

- ^ Burak, Guy (2015). The Second Formation of Islamic Law: The Ḥanafī School in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-107-09027-9.

- ^ "1548–49". The Encyclopedia of World History. 2001. Archived from the original on 18 September 2002. Retrieved 20 June 2020 – via Bartleby.com.

- ^ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. xxxi. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- ^ The Reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, 1520–1566, V.J. Parry, A History of the Ottoman Empire to 1730, ed. M.A. Cook (Cambridge University Press, 1976), 94.

- ^ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 698. ISBN 978-1598843361.

- ^ Özcan, Azmi (1997). Pan-Islamism: Indian Muslims, the Ottomans and Britain, 1877–1924. Brill. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-90-04-10632-1. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Farooqi, N. R. (1996). "Six Ottoman documents on Mughal-Ottoman relations during the reign of Akbar". Journal of Islamic Studies. 7 (1): 32–48. doi:10.1093/jis/7.1.32.

- ^ Farooqi, Naimur Rahman (1989). Mughal-Ottoman relations: a study of political & diplomatic relations between Mughal India and the Ottoman Empire, 1556–1748. Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Kour, Z. H. (2005). The History of Aden. Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-135-78114-9.

- ^ İnalcik, Halil (1997). An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-521-57456-3.

- ^ History of the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey by Ezel Kural Shaw p. 107 [1] Archived 26 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "similarities between louis xiv and suleiman the magnificent". gymwp.app. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ Clifford, E. H. M. (1936). "The British Somaliland-Ethiopia Boundary". Geographical Journal. 87 (4): 289–302. Bibcode:1936GeogJ..87..289C. doi:10.2307/1785556. JSTOR 1785556.

- ^ Black, Jeremy (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: Renaissance to Revolution, 1492–1792, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-521-47033-1.

- ^ Coins From Mogadishu, c. 1300 to c. 1700 by G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville, p. 36

- ^ Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1976). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0871691613 – via Google Books.

- ^ A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period Jamil M. Abun-Nasr p. 190 [2]

- ^ A History of the Ottoman Empire to 1730: chapters from the Cambridge history by Vernon J. Parry p. 101 [3]

- ^ Mitev, Georgi. "History of Malta and Gozo – From Prehistory to Independence".

- ^ Greenblatt, Miriam (2003). Süleyman the Magnificent and the Ottoman Empire. New York: Benchmark Books. ISBN 978-0-7614-1489-6.

- ^ McCarthy, Justin (1997). The Ottoman Turks: An Introductory History to 1923. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-582-25655-2.

- ^ "Muhibbî (Kanunî Sultan Süleyman)". turkcebilgi.org. Türkçe Bilgi, Ansiklopedi, Sözlük.

- ^ "Halman, Suleyman the Magnificent Poet". Archived from the original on 9 March 2006.

- ^ Atıl, 26.

- ^ "Istanbul's signature flowers, plants in cologne bottles". Daily Sabah. 27 April 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Kling, Cynthia (12 October 2017). "Wild Tulips: Get In On This Gardening Trend Now". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Osman, Nadda (24 January 2022). "Five national flowers from the Middle East and the symbolism they hold". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Amsterdam Tulip Museum, "The Tulip in Turkey," accessed September 17, 2024, https://amsterdamtulipmuseum.com/pages/the-tulip-in-turkey.

- ^ Freely, John (1 July 2001). Inside the Seraglio: Private Lives of the Sultans in Istanbul. Penguin. ISBN 9780140270563.

- ^ Yermolenko, Galina I (2013). Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culturea. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-4094-7611-5.

- ^ Peirce 1993, p. 60.

- ^ Uzunçarşılı, İsmail Hakkı; Karal, Enver Ziya (1975). Osmanlı tarihi, Volume 2. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi. p. 401.

- ^ Şahin, K. (2023). Peerless Among Princes: The Life and Times of Sultan Süleyman. Oxford University Press. pp. 99, 120. ISBN 978-0-19-753163-1.

- ^ Peirce 2017, p. 58.

- ^ Okan, A. (2008). İstanbul evliyaları. Kapı yayınları. Kapı yayınları. p. 17. ISBN 978-9944-486-70-5.

- ^ Yermolenko 2005, p. 233.

- ^ Uluçay 1992, p. 65.

- ^ Ahmed, 43.

- ^ "A 400 Year Old Love Poem". Women in World History.

- ^ Gökbilgin, M. Tayyib (24 April 2012), "Ibrāhīm Pas̲h̲a", Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Brill, retrieved 2 August 2022

- ^ Baer, Marc David (2021). The Ottomans: Khans, Caesars, and Caliphs (First ed.). New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-5416-7380-9. OCLC 1236896222.

- ^ Turan, Ebru (2009). "The Marriage of Ibrahim Pasha (ca. 1495–1536): The Rise of Sultan Süleyman's Favorite to the Grand Vizierate and the Politics of the Elites in the Early Sixteenth-Century Ottoman Empire". Turcica. 41: 3–36. doi:10.2143/TURC.41.0.2049287. Archived from the original on 30 April 2024 – via Peeters Online Journals.

- ^ Turan, Ebru. The sultan's favorite : İbrahim Pasha and the making of the Ottoman universal sovereignty in the reign of Sultan Süleyman (1516-1526) pp 139-140. OCLC 655885125.

- ^ Hester Donaldson Jenkins, Ibrahim Pasha: grand vizir of Suleiman the Magnificent (1911) pp 109–125.online

- ^ Ünal, Tahsin (1961). The Execution of Prince Mustafa in Eregli. Anıt. pp. 9–22.

- ^ Ágoston, Gábor (1991). "Muslim Cultural Enclaves in Hungary under Ottoman Rule". Acta Orientalia Scientiarum Hungaricae. 45: 197–98.

- ^ Howard, Douglas (1988). "Ottoman Historiography and the Literature of 'Decline' of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries". Journal of Asian History. 22.

- ^ Lewis, 10.

- ^ Ahmed, 147.

- ^ "The Merchant of Venice: Act 2, Scene 1, Page 2". No Fear Shakespeare. SparkNotes. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ "Shakespeare's Merchant: St Antony and Sultan Suleiman – The Merchant Of Venice – Shylock". Scribd.

- ^ Russell, John (26 January 2007). "The Age of Sultan Suleyman". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ^ Halil İnalcık (1973). The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300–1600. p. 41.

- ^ "Sculpture". Joseph Kiselewski. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Suleiman, Relief Portrait | Architect of the Capitol". www.aoc.gov.

References

Printed sources

- Ágoston, Gábor (1991). "Muslim Cultural Enclaves in Hungary under Ottoman Rule". Acta Orientalia Scientiarum Hungaricae. 45: 181–204.

- Ahmed, Syed Z (2001). The Zenith of an Empire : The Glory of the Suleiman the Magnificent and the Law Giver. A.E.R. Publications. ISBN 978-0-9715873-0-4.

- Arsan, Esra; Yldrm, Yasemin (2014). "Reflections of neo-Ottomanist discourse in Turkish news media: The case of The Magnificent Century". Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies. 3 (3): 315–334. doi:10.1386/ajms.3.3.315_1.

- Atıl, Esin (1987). The Age of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-89468-098-4.

- Barber, Noel (1976). Lords of the Golden Horn : From Suleiman the Magnificent to Kamal Ataturk. London: Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-24735-1.

- Clot, André. Suleiman the magnificent (Saqi, 2012).

- Garnier, Edith L'Alliance Impie Editions du Felin, 2008, Paris ISBN 978-2-86645-678-8 Interview

- Işıksel, Güneş (2018). "Suleiman the Magnificent (1494-1566)". In Martel, Gordon (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Diplomacy. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781118885154.dipl0267. ISBN 9781118887912.

- Levey, Michael (1975). The World of Ottoman Art. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27065-1.

- Lewis, Bernard (2002). What Went Wrong? : Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-1675-2.

- Lybyer, Albert Howe. The Government of the Ottoman Empire in the Time of Suleiman the Magnificent (Harvard UP, 1913) online.

- Merriman, Roger Bigelow (1944). Suleiman the Magnificent, 1520–1566. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC 784228.

- Norwich, John Julius. Four princes: Henry VIII, Francis I, Charles V, Suleiman the Magnificent and the obsessions that forged modern Europe (Grove/Atlantic, 2017) popular history.

- Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508677-5.

- Peirce, Leslie P. (2017). Empress of the East : How a slave girl became queen of the Ottoman Empire. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03251-8.

- Uluçay, Mustafa Çağatay (1992). Padışahların kadınları ve kızları. Türk Tarihi Kurumu Yayınları.

- Yermolenko, Galina (2005). "Roxolana: The Greatest Empress of the East". The Muslim World. 95 (2): 231–248. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.2005.00088.x.

- "Suleiman The Lawgiver". Saudi Aramco World. 15 (2). Houston, Texas: Aramco Services Co: 8–10. March–April 1964. ISSN 1530-5821. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

Additional on-line sources

- Yalman, Suzan (2000). "The Age of Süleyman 'the Magnificent' (r. 1520–1566)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Based on original work by Linda Komaroff.

- Yapp, Malcolm Edward (2007). "Suleiman I". Microsoft Encarta. Archived from the original on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2008.

Further reading

- Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1923. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

- İnalcık, Halil; Cemal Kafadar, eds. (1993). Süleyman the Second and His Time. Istanbul: The Isis Press. ISBN 975-428-052-5.; deals with Suleiman 1494–1566

- Lamb, Harold. Suleiman the Magnificent Sultan of the East (1951) online

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (2005). The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691123264. OCLC 1204337149.

- Parry, V. J. "The Ottoman Empire, 1520–1566." in The New Cambridge Modern History II: The Reformation 1520–1559 (2nd ed 1990): 570–594 online

- Yermolenko, Galina I., ed. Roxolana in European literature, history and culture Archived 26 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine (Routledge, 2016) ISBN 9780754667612