The Rhine

Its name derives from the Gaulish Rēnos. There are two German states named after the river, North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate, in addition to several districts (e.g. Rhein-Sieg). The departments of Bas-Rhin and Haut-Rhin in Alsace (France) are also named after the river. Some adjacent towns are named after it, such as Rheinau, Rheineck, Rheinfelden (CH) and Rheinfelden (D).

The International Commission for the Hydrology of the Rhine Basin (CHR) and EUWID contend that the river could experience a massive decrease in volume, or even dry up completely in case of drought, within the next 30 to 80 years, as a result of the climate crisis.

The Rhine is the second-longest river in Central and Western Europe (after the Danube), at about 1,230 km (760 mi), with an average discharge of about 2,900 m/s (100,000 cu ft/s).

The Rhine and the Danube comprised much of the Roman Empire's northern inland boundary, and the Rhine has been a vital navigable waterway bringing trade and goods deep inland since those days. The various castles and defenses built along it attest to its prominence as a waterway in the Holy Roman Empire. Among the largest and most important cities on the Rhine are Cologne, Rotterdam, Düsseldorf, Duisburg, Strasbourg, Arnhem, and Basel.

Name

The variants of the name of the Rhine (Latin Rhenus; French Rhin, Italian Reno, Romansh Rain or Rein, Dutch Rijn, Alemannic Ry, Ripuarian Rhing) in modern languages are all derived from the Gaulish name Rēnos, which was adapted in Roman-era geography (1st century BC) as Latin Rhenus, and as Greek Ῥῆνος (Rhēnos).

The spelling with Rh- in English Rhine as well as in German Rhein and French Rhin is due to the influence of Greek orthography, while the vocalization -i- is due to the Proto-Germanic adoption of the Gaulish name as *Rīnaz, via Old Frankish giving Old English Rín, Old High German Rīn, early Middle Dutch (c. 1200) Rijn (then also spelled Ryn or Rin).

The modern German diphthong Rhein (also used in Romansh) Rein, Rain is a Central German development of the early modern period, with the Alemannic name R(n) keeping the older vocalism. In Alemannic, the deletion of the ending -n in pausa is a recent development; the form Rn is largely preserved in Lucernese dialects. Rhing in Ripuarian is diphthongized, as is Rhei, Rhoi in Palatine. While Spanish has adopted the Germanic vocalism Rin-, Italian, Occitan, and Portuguese have retained the Latin Ren-.

The Gaulish name Rēnos (Proto-Celtic or pre-Celtic *Reinos) belongs to a class of river names built from the PIE root *rei- "to move, flow, run", also found in other names such as the Reno in Italy.

The grammatical gender of the Celtic name (as well as of its Greek and Latin adaptation) is masculine, and the name remains masculine in German, Dutch, French, Spanish and Italian. The Old English river name was variously inflected as masculine or feminine; and its Old Icelandic adoption was inflected as feminine.

Geography

The length of the Rhine is conventionally measured in "Rhine-kilometers" (Rheinkilometer), a scale introduced in 1939 which runs from the 0 km datum at Old Rhine Bridge in the city of Konstanz, at the western end of Lake Constance, to the Hook of Holland at 1,036.20 km.

The river is significantly shortened from its natural course due to a number of canal projects completed in the 19th and 20th century. The "total length of the Rhine", to the inclusion of Lake Constance and the Alpine Rhine is more difficult to measure objectively; it was cited as 1,232 kilometers (766 miles) by the Dutch Rijkswaterstaat in 2010.

Its course is conventionally divided as follows:

| Length | Section | Avg. discharge | Elevation | Left tributaries | Right tributaries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 76 km | The various sources and headwaters forming the Anterior and Posterior Rhine within Grisons, Switzerland | 116 m/s | 584 m | Aua Russein, Schmuèr | Rein da Tuma, Rein da Curnera, Rein da Medel, Rein da Sumvitg (Rein da Vigliuts), Glogn (Valser Rhine), Rabiusa, Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein (tributaries of which include the Ragn da Ferrera, Albula/Alvra, Gelgia, and Landwasser) |

| c. 90 km | The Alpine Rhine running through the Grisonian and St. Gall Rhine Valley (partly forming the Swiss border with Liechtenstein and Austria) | 245 m/s | 400 m | Tamina, Saar | Plessur, Landquart, Liechtenstein inland canal, Ill, Frutz |

| c. 60 km | Lake Constance, including the short channel called Seerhein at Konstanz, connecting Obersee and Untersee | 364 m/s | 395 m | Alter Rhein (Rheintaler Binnenkanal), Goldach, Aach | Dornbirner Ach, Bregenzer Ach, Leiblach, Argen, Schussen, Rotach, Brunnisach, Lipbach, Seefelder Aach, Stockacher Aach, Radolfzeller Aach |

| c. 150 km | The High Rhine from the exit of Lake Constance to Basel, forming a substantial part of the German-Swiss border | 1,089 m/s | 246 m | Thur, Töss, Glatt, Aare, Sissle. Möhlinbach, Ergolz, Birs | Biber, Durach, Wutach, Alb, Murg, Wehra |

| 362 km | The Upper Rhine from Basel to Bingen forming the Upper Rhine Plain and in its upper course the Franco-German border | 79 m | Birsig, Ill, Moder, Lauter, Nahe | Wiese, Kander, Elz, Kinzig, Rench, Acher, Murg, Alb, Pfinz, Neckar, Main | |

| 159 km | The Middle Rhine between Bingen and either Bonn or Cologne is entirely within Germany, passing the Rhine Gorge; | 45 m | Moselle, Nette, Ahr | Lahn, Wied, Sieg | |

| 177 km | The Lower Rhine or Niederrhein downstream of Bonn, passing the Lower Rhine region of North Rhine-Westphalia | 11 m | Erft | Wupper, Düssel, Ruhr, Emscher, Lippe | |

| c. 50 km | The Nether Rhine or Nederrijn (shortened course of Oude Rijn within the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta in the Netherlands) | 2,900 m/s | 0 m | Meuse | Oude IJssel, Berkel |

- ^ Partial list.

- ^ Length of the Anterior Rhine, including the Rein da Medel; 47 mi.

- ^ Average runoff for the Rhine catchment for the years 1961–1990 as measured at Chur.

- ^ 56 mi.

- ^ Average runoff for the Rhine catchment for the years 1961–1990 as measured at the Swiss border immediately upstream of Lake Constance.

- ^ 37 mi.

- ^ Average runoff for the Rhine and Lake Constance catchment for the years 1961–1990 as measured at Rheinklingen.

- ^ Most of the water of the Radolfzeller Aach comes from the Danube Sinkhole, making the Danube indirectly a tributary of the Rhine.

- ^ Konstanz to Basel, Rheinkilometer 0–167; 93 mi.

- ^ Average discharge for the years 1961–1990 as measured at Basel. Discharges of 2,500 m/s are regularly achieved during annual peaks, and discharges of over 4,000 m/s have been recorded during exceptional flooding events.

- ^ At the confluence of the Aare and the Rhine, the Aare at 564 m/s carries more water on average than the Rhine at 442 m/s, so that hydrographically speaking the Rhine is a right tributary of the Aare.

- ^ Basel to Bingen, Rheinkilometer 167–529; 225 mi.

- ^ Bingen to Cologne, Rheinkilometer 529–688; 99 mi.

- ^ Cologne to the Dutch-German border, Rheinkilometer 688–865.5; 110 mi.

- ^ 31 mi.

- ^ The total discharge of the Rhine is subject to significant fluctuations, and average values cited vary between sources; the total discharge given here consists of: Maasmond, 1450 m/s; Haringvliet, 820 m/s; Den Oever, 310 m/s; Kornwerderzand, 220 m/s; IJmuiden, 9 m/s; and the Scheldt–Rhine Canal, 10 m/s.

Headwaters and sources

Sources

The Rhine carries its name without distinctive accessories only from the confluence of the Rein Anteriur/Vorderrhein and Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein next to Reichenau in Tamins. Above this point is the extensive catchment area of the headwaters of the Rhine. This area belongs almost exclusively to the Swiss canton of Grisons (Graubünden), ranging from Saint-Gotthard Massif in the west via one valley lying in the canton of Ticino and Sondrio (Lombardy, Italy) in the south to the Flüela Pass in the east. The Rhine is one of four major rivers taking their source in the Gotthard region, along with the Ticino (drainage basin of the Po), Rhône and Reuss (Rhine basin). The Witenwasserenstock is the triple watershed between the Rhine, Rhône and Po.

Traditionally, Lake Toma near the Oberalp Pass in the Gotthard region is seen as the source of the Anterior Rhine and the Rhine as a whole. The Posterior Rhine rises in the Rheinwald below the Rheinwaldhorn.

Anterior Rhine and Posterior Rhine

The source of the river is generally considered north of Lai da Tuma/Tomasee on Rein Anteriur/Vorderrhein, although its southern tributary Rein da Medel is actually longer before its confluence with the Anterior Rhine near Disentis.

- The Anterior Rhine (Romansh: Rein Anteriur, German: Vorderrhein) springs from Lai da Tuma/Tomasee, near the Oberalp Pass and passes the impressive Ruinaulta formed by the largest visible rock slide in the alps, the Flims Rockslide.

- The Posterior Rhine (Romansh: Rein Posteriur, German: Hinterrhein) starts from the Paradies Glacier, near the Rheinwaldhorn. One of its tributaries, the Reno di Lei, drains the Valle di Lei on politically Italian territory. After three main valleys separated by the two gorges, Roflaschlucht and Viamala, it reaches Reichenau in Tamins.

The Anterior Rhine arises from numerous source streams in the upper Surselva and flows in an easterly direction. One source is Lai da Tuma (2,345 m (7,694 ft)) with the Rein da Tuma, which is usually indicated as source of the Rhine, flowing through it.

Into it flow tributaries from the south, some longer, some equal in length, such as the Rein da Medel, the Rein da Maighels, and the Rein da Curnera. The Cadlimo Valley in the canton of Ticino is drained by the Reno di Medel, which crosses the geomorphologic Alpine main ridge from the south. All streams in the source area are partially, sometimes completely, captured and sent to storage reservoirs for the local hydro-electric power plants.

The culminating point of the Anterior Rhine's drainage basin is the Piz Russein of the Tödi massif of the Glarus Alps at 3,613 meters (11,854 ft) above sea level. It starts with the creek Aua da Russein (lit.: "Water of the Russein").

In its lower course, the Anterior Rhine flows through a gorge named Ruinaulta (Flims Rockslide). The whole stretch of the Anterior Rhine to the Alpine Rhine confluence next to Reichenau in Tamins is accompanied by a long-distance hiking trail called Senda Sursilvana.

The Posterior Rhine flows first east-northeast, then north. It flows through the three valleys named Rheinwald, Schams and Domleschg-Heinzenberg. The valleys are separated by the Rofla Gorge and Viamala Gorge. Its sources are located in the Adula Alps (Rheinwaldhorn, Rheinquellhorn, and Güferhorn).

The Avers Rhine joins from the south. One of its headwaters, the Reno di Lei (stowed in the Lago di Lei), is partially located in Italy.

Near Sils the Posterior Rhine is joined by the Albula, from the east, from the Albula Pass region. The Albula draws its water mainly from the Landwasser with the Dischmabach as the largest source stream, but almost as much from the Gelgia, which comes down from the Julier Pass.

Numerous larger and smaller tributary rivers bear the name of the Rhine or equivalent in various Romansh idioms, including Rein or Ragn, including:

- Anterior Rhine area: Rein Anteriur/Vorderrhein, Rein da Medel, Rein da Tuma, Rein da Curnera, Rein da Maighels, Rein da Cristallina, Rein da Nalps, Rein da Plattas, Rein da Sumvitg, Rein da Vigliuts, Valser Rhine

- Posterior Rhine basin: Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein, Reno di Lei, Madrischer Rhein, Avers Rhine, Jufer Rhein

- Albula-Landwasser area: In the Dischma valley, near Davos, far east of the Rhine, there's a place called Am Rin ("Upon Rhine"). A tributary of the Dischma is called Riner Tälli. Nearby, on the other side of the Sertig, is the Rinerhorn.

Alpine Rhine

Next to Reichenau in Tamins the Anterior Rhine and the Posterior Rhine join and form the Alpine Rhine. The river makes a distinctive turn to the north near Chur. This section is nearly 86 km long, and descends from a height of 599 meters to 396 meters. It flows through a wide glacial Alpine valley known as the Rhine Valley (German: Rheintal). Near Sargan a natural dam, only a few meters high, prevents it from flowing into the open Sztal valley and then through Lake Walen and Lake Zurich into the Aare. The Alpine Rhine begins in the westernmost part of the Swiss canton of Graubünden, and later forms the border between Switzerland to the west and Liechtenstein and later Austria to the east.

As an effect of human work, it empties into Lake Constance on Austrian territory and not on the border that follows its old natural river bed called Alter Rhein (lit. 'Old Rhine').

The mouth of the Rhine into Lake Constance forms an inland delta. The delta is delimited in the west by the Alter Rhein and in the east by the modern canalized section of the Alpine Rhine (Fußacher Durchstich). Most of the delta is a nature reserve and bird sanctuary. It includes the Austrian towns of Gaißau, Höchst and Fußach. The natural Rhine originally branched into at least two arms and formed small islands by precipitating sediments. In the local Alemannic dialect, the singular is pronounced "Isel" and this is also the local pronunciation of Esel ("Donkey"). Many local fields have an official name containing this element.

A regulation of the Rhine was called for, with an upper canal near Diepoldsau and a lower canal at Fußach, in order to counteract the constant flooding and strong sedimentation in the western Rhine Delta. The Dornbirner Ach had to be diverted, too, and it now flows parallel to the canalized Rhine into the lake. Its water has a darker color than the Rhine; the latter's lighter suspended load comes from higher up the mountains. It is expected that the continuous input of sediment into the lake will silt up the lake. This has already happened to the former Lake Tuggenersee.

The cut-off Old Rhine at first formed a swamp landscape. Later an artificial ditch of about two km was dug. It was made navigable to the Swiss town of Rheineck.

Lake Constance

Lake Constance consists of three bodies of water: the Obersee ("upper lake"), the Untersee ("lower lake"), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, called the Seerhein ("Lake Rhine"). The lake is situated in Germany, Switzerland and Austria near the Alps. Specifically, its shorelines lie in the German states of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, the Austrian state of Vorarlberg, and the Swiss cantons of Thurgau and St. Gallen. The Rhine flows into it from the south following the Swiss-Austrian border. It is located at approximately 47°39′N 9°19′E / 47.650°N 9.317°E.

Obersee

The flow of cold, grey mountain water continues for some distance into the lake. The cold water flows near the surface and at first does not mix with the warmer, green waters of Upper Lake. But then, at the so-called Rheinbrech, the Rhine water abruptly falls into the depths because of the greater density of cold water. The flow reappears on the surface at the northern (German) shore of the lake, off the island of Lindau. The water then follows the northern shore until Hagnau am Bodensee. A small fraction of the flow is diverted off the island of Mainau into Lake Überlingen. Most of the water flows via the Constance hopper into the Rheinrinne ("Rhine Gutter") and Seerhein. Depending on the water level, this flow of the Rhine water is clearly visible along the entire length of the lake.

The Rhine carries very large amounts of debris into the lake – over three million cubic meters (110,000,000 cu ft) annually. In the mouth region, it is therefore necessary to permanently remove gravel by dredging. The large sediment loads are partly due to the extensive land improvements upstream.

Three countries border the Obersee, namely Switzerland in the south, Austria in the southeast and the German states of Bavaria in the northeast and Baden-Württemberg in the north and northwest.

Seerhein

The Seerhein is only 4 kilometers (2.5 mi) long. It connects the Obersee with the 30 cm lower Untersee. Distance markers along the Rhine measure the distance from the bridge in the old city center of Konstanz.

For most of its length, the Seerhein forms the border between Germany and Switzerland. The exception is the old city center of Konstanz, on the Swiss side of the river.

The Seerhein emerged in the last thousands of years, when erosion caused the lake level to be lowered by about 10 meters. Previously, the two lakes formed a single lake, as the name still suggests.

Untersee

Like in the Obersee, the flow the Rhine can be traced in the Untersee. Here, too, the river water is hardly mixed with the lake water. The northern parts of the Untersee (Lake Zell and Gnadensee) remain virtually unaffected by the flow. The river traverses the southern, which, in isolation, is sometimes called Rhinesee ("Lake Rhine").

Besides the Seerhein, the Radolfzeller Aach is the main tributary of Untersee. It adds large amounts of water from the Danube system to the Untersee via the Danube Sinkhole.

Reichenau Island was formed at the same time as the Seerhein, when the water level fell to its current level.

Lake Untersee is part of the border between Switzerland and Germany, with Germany on the north bank and Switzerland on the south, except both sides are Swiss in Stein am Rhein, where the High Rhine flows out of the lake.

High Rhine

The High Rhine (Hochrhein) begins in Stein am Rhein at the western end of the Untersee. Now flowing generally westwards, it passes over the Rhine Falls (Rheinfall) below Schaffhausen before being joined – near Koblenz in the canton of Aargau – by its major tributary, the Aare. The Aare more than doubles the Rhine's water discharge, to an average of slightly more than 1,000 m/s (35,000 cu ft/s), and provides more than a fifth of the discharge at the Dutch border. The Aare also contains the waters from the 4,274 m (14,022 ft) summit of Finsteraarhorn, the highest point of the Rhine basin.

Between Eglisau and Basel, the vast majority of its length, the High Rhine forms the border between Germany and Switzerland. Only for brief distances at its extremities does the river run entirely within Switzerland; at the eastern end it separates the bulk of the canton of Schaffhausen and the German exclave of Büsingen am Hochrhein on the northern bank from cantons of Zürich and Thurgau, while at the western end it bisects the canton of Basel-Stadt. Here, at the Rhine knee, the river turns north and leaves Switzerland altogether.

The High Rhine is characterized by numerous dams. On the few remaining natural sections, there are still several rapids. Over its entire course from Lake Constance to the Swiss border at Basel the river descends from 395 m to 252 m.

Upper Rhine

In the center of Basel, the first major city in the course of the stream, is the Rhine knee, a major bend, where the overall direction of the Rhine changes from west to north. Here the High Rhine ends. Legally, the Central Bridge is the boundary between High and Upper Rhine. The river now flows north as Upper Rhine through the Upper Rhine Plain, which is about 300 km long and up to 40 km wide. The most important tributaries in this area are the Ill below of Strasbourg, the Neckar in Mannheim and the Main across from Mainz. In Mainz, the Rhine leaves the Upper Rhine Valley and flows through the Mainz Basin.

The southern half of the Upper Rhine forms the border between France (Alsace) and Germany (Baden-Württemberg). The northern part forms the border between the German states of Rhineland-Palatinate in the west on the one hand, and Baden-Württemberg and Hesse on the other hand, in the east and north. A curiosity of this border line is that the parts of the city of Mainz on the right bank of the Rhine were given to Hesse by the occupying forces in 1945.

The Upper Rhine was a significant cultural landscape in Central Europe already in antiquity and during the Middle Ages. Today, the Upper Rhine area hosts many important manufacturing and service industries, particularly in the centers Basel, Strasbourg and Mannheim-Ludwigshafen. Strasbourg is the seat of the European Parliament, and so one of the three European capitals is located on the Upper Rhine.

The Upper Rhine region was changed significantly by a Rhine straightening program in the 19th century. The rate of flow was increased and the ground water level fell significantly. Dead branches were removed by construction workers and the area around the river was made more habitable for humans on flood plains as the rate of flooding decreased sharply. On the French side, the Grand Canal d'Alsace was dug, which carries a significant part of the river water, and all of the traffic. In some places, there are large compensation pools, for example, the huge Bassin de compensation de Plobsheim in Alsace.

The Upper Rhine has undergone significant human change since the 19th century. While it was slightly modified during the Roman occupation, it was not until the emergence of engineers such as Johann Gottfried Tulla that significant modernization efforts changed the shape of the river. Earlier work under Frederick the Great surrounded efforts to ease shipping and construct dams to serve coal transportation. Tulla is considered to have domesticated the Upper Rhine, a domestication that served goals such as reducing stagnant bogs that fostered waterborne diseases, making regions more habitable for human settlement, and reduce high frequency of floods. Not long before Tulla went to work on widening and straightening the river, heavy floods caused significant loss of life. Four diplomatic treaties were signed among German state governments and French regions dealing with the changes proposed along the Rhine, one was "the Treaty for the Rectification of the Rhine flow from Neuberg to Dettenheim"(1817), which surrounded states such as Bourbon France and the Bavarian Palatinate. Loops, oxbows, branches and islands were removed along the Upper Rhine so that there would be uniformity to the river. The engineering of the Rhine was not without protest, farmers and fishermen had grave concerns about valuable fishing areas and farmland being lost. While some areas lost ground, other areas saw swamps and bogs be drained and turned into arable land. Johann Tulla had the goal of shortening and straightening the Upper Rhine. Early engineering projects the Upper Rhine also had issues, with Tulla's project at one part of the river creating rapids, after the Rhine cut down from erosion to sheer rock. Engineering along the Rhine eased flooding and made transportation along the river less cumbersome. These state projects were part of the advanced and technical progress going on in the country alongside the industrial revolution. For the German state, making the river more predictable was to ensure development projects could easily commence.

The section of the Upper Rhine downstream from Mainz is also known as the "Island Rhine". Here a number of river islands occur, locally known as "Rheinauen".

Middle Rhine

The Rhine is the longest river in Germany. It is here that the Rhine encounters some more of its main tributaries, such as the Neckar, the Main and, later, the Moselle, which contributes an average discharge of more than 300 m/s (11,000 cu ft/s). Northeastern France drains to the Rhine via the Moselle; smaller rivers drain the Vosges and Jura Mountains uplands. Most of Luxembourg and a very small part of Belgium also drain to the Rhine via the Moselle. As it approaches the Dutch border, the Rhine has an annual mean discharge of 2,290 m/s (81,000 cu ft/s) and an average width of 400 m (1,300 ft).

Between Bingen am Rhein and Bonn, the Middle Rhine flows through the Rhine Gorge, a formation which was created by erosion. The rate of erosion equaled the uplift in the region, such that the river was left at about its original level while the surrounding lands raised. The gorge is quite deep and is the stretch of the river which is known for its many castles and vineyards. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site (2002) and known as "the Romantic Rhine", with more than 40 castles and fortresses from the Middle Ages and many quaint and lovely country villages.

-

Between Strasbourg and Kehl

-

The Rhine in Cologne

-

Rhine at Düsseldorf

-

Rhine at Hünxe, near the border of the Netherlands

The Mainz Basin ends in Bingen am Rhein; the Rhine continues as "Middle Rhine" into the Rhine Gorge in the Rhenish Slate Mountains. In this sections the river falls from 77.4 m above sea level to 50.4 m. On the left, is located the mountain ranges of Hunsrück and Eifel, on the right Taunus and Westerwald. According to geologists, the characteristic narrow valley form was created by erosion by the river while the surrounding landscape was lifted (see water gap).

Major tributaries in this section are the Lahn and the Moselle. They join the Rhine near Koblenz, for the right and left respectively. Almost the entire length of the Middle Rhine runs in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate.

The dominant economic sectors in the Middle Rhine area are viniculture and tourism. The Rhine Gorge between Rüdesheim am Rhein and Koblenz is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Near Sankt Goarshausen, the Rhine flows around the famous rock Lorelei. With its outstanding architectural monuments, the slopes full of vines, settlements crowded on the narrow river banks and scores of castles lined up along the top of the steep slopes, the Middle Rhine Valley can be considered the epitome of the Rhine romanticism.

Lower Rhine

In Bonn, where the Sieg flows into the Rhine, the Rhine enters the North German Plain and turns into the Lower Rhine. The Lower Rhine falls from 50 m to 12 m. The main tributaries on this stretch are the Ruhr and the Lippe. Like the Upper Rhine, the Lower Rhine used to meander until engineering created a solid river bed. Because the levees are some distance from the river, at high tide the Lower Rhine has more room for widening than the Upper Rhine.

The Lower Rhine flows through North Rhine-Westphalia. Its banks are usually heavily populated and industrialized, in particular the agglomerations Cologne, Düsseldorf and Ruhr area. Here the Rhine flows through the largest conurbation in Germany, the Rhine-Ruhr region. One of the most important cities in this region is Duisburg with the largest river port in Europe (Duisport). The region downstream of Duisburg is more agricultural. In Wesel, 30 km downstream of Duisburg, is located the western end of the second east–west shipping route, the Wesel-Datteln Canal, which runs parallel to the Lippe. Between Emmerich and Cleves the Emmerich Rhine Bridge, the longest suspension bridge in Germany, crosses the 400-meter-wide (1,300 ft) river. Near Krefeld, the river crosses the Uerdingen line, the line which separates the areas where Low German and High German are spoken. The Rhine River is crossed by several ferries, including the one between Bad Honnef and Rolandseck, where the Lohfelderfähre district is situated.

Until the early 1980s, industry was a major source of water pollution. Although many plants and factories can be found along the Rhine up into Switzerland, it is along the Lower Rhine that the bulk of them are concentrated, as the river passes the major cities of Cologne, Düsseldorf and Duisburg. Duisburg is the home of Europe's largest inland port and functions as a hub to the sea ports of Rotterdam, Antwerp and Amsterdam. The Ruhr, which joins the Rhine in Duisburg, is nowadays a clean river, thanks to a combination of stricter environmental controls, a transition from heavy industry to light industry and cleanup measures, such as the reforestation of Slag and brownfields. The Ruhr currently provides the region with drinking water. It contributes 70 m/s (2,500 cu ft/s) to the Rhine. Other rivers in the Ruhr Area include the Emscher.

Delta

The Dutch name for Rhine is "Rijn". The Rhine turns west and enters the Netherlands, where, together with the rivers Meuse and Scheldt, it forms the extensive Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt delta, with 25,347 km (9,787 sq mi) the largest river delta in Europe. Crossing the border into the Netherlands at Spijk, close to Nijmegen and Arnhem, the Rhine is at its widest, although the river then splits into three main distributaries: the Waal, Nederrijn ("Nether Rhine") and IJssel.

From here, the situation becomes more complicated, as the Dutch name Rijn no longer coincides with the main flow of water. Two-thirds of the water flow volume of the Rhine flows farther west, through the Waal and then, via the Merwede and Nieuwe Merwede (De Biesbosch), merging with the Meuse, through the Hollands Diep and Haringvliet estuaries, into the North Sea. The Beneden Merwede branches off, near Hardinxveld-Giessendam and continues as the Noord, to join the Lek, near the village of Kinderdijk, to form the Nieuwe Maas; then flows past Rotterdam and continues via Het Scheur and the Nieuwe Waterweg, to the North Sea. The Oude Maas branches off, near Dordrecht, farther down rejoining the Nieuwe Maas to form Het Scheur.

The other third of the water flows through the Pannerdens Kanaal and redistributes in the IJssel and Nederrijn. The IJssel branch carries one ninth of the water flow of the Rhine north into the IJsselmeer (a former bay), while the Nederrijn carries approximately two-ninths of the flow west along a route parallel to the Waal. However, at Wijk bij Duurstede, the Nederrijn changes its name and becomes the Lek. It flows farther west, to rejoin the Noord into the Nieuwe Maas and to the North Sea.

The name Rijn, from here on, is used only for smaller streams farther to the north, which together formed the main river Rhine in Roman times. Though they retained the name, these streams no longer carry water from the Rhine, but are used for draining the surrounding land and polders. From Wijk bij Duurstede, the old north branch of the Rhine is called Kromme Rijn ("Bent Rhine") past Utrecht, first Leidse Rijn ("Rhine of Leiden") and then, Oude Rijn ("Old Rhine"). The latter flows west into a sluice at Katwijk, where its waters can be discharged into the North Sea. This branch once formed the line along which the Limes Germanicus were built. During periods of lower sea levels within the various ice ages, the Rhine took a left turn, creating the Channel River, the course of which now lies below the English Channel.

The Rhine-Meuse Delta, the most important natural region of the Netherlands begins near Millingen aan de Rijn, close to the Dutch-German border with the division of the Rhine into Waal and Nederrijn. The region between the Dutch-German border and Rotterdam, where the Waal, Lek, and Meuse run more or less parallel, is colloquially known as the "Great Rivers". Since the Rhine contributes most of the water, the shorter term Rhine Delta is commonly used. However, this name is also used for the river delta where the Rhine flows into Lake Constance, so it is clearer to call the larger one Rhine-Meuse delta, or even Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, as the Scheldt ends in the same delta.

The shape of the Rhine delta is determined by two bifurcations: first, at Millingen aan de Rijn, the Rhine splits into Waal and Pannerdens Kanaal, which changes its name to Nederrijn at Angeren, and second near Arnhem, the IJssel branches off from the Nederrijn. This creates three main flows, two of which change names rather often. The largest and southern main branch begins as Waal and continues as Boven Merwede ("Upper Merwede"), Beneden Merwede ("Lower Merwede"), Noord ("the North"), Nieuwe Maas ("New Meuse"), Het Scheur ("the Rip") and Nieuwe Waterweg ("New Waterway"). The middle flow begins as Nederrijn, then changes into Lek, then joins the Noord, thereby forming Nieuwe Maas. The northern flow keeps the name IJssel until it flows into Lake IJsselmeer. Three more flows carry significant amounts of water: the Nieuwe Merwede ("New Merwede"), which branches off from the southern branch where it changes from Boven to Beneden Merwede; the Oude Maas ("Old Meuse"), which branches off from the southern branch where it changes from Beneden Merwede into Noord, and Dordtse Kil, which branches off from Oude Maas.

Before the St. Elizabeth's flood (1421), the Meuse flowed just south of today's line Merwede-Oude Maas to the North Sea and formed an archipelago-like estuary with Waal and Lek. This system of numerous bays, estuary-like extended rivers, many islands and constant changes of the coastline, is hard to imagine today. From 1421 to 1904, the Meuse and Waal merged further upstream at Gorinchem to form Merwede. For flood protection reasons, the Meuse was separated from the Waal through a lock and diverted into a new outlet called "Bergse Maas", then Amer and then flows into the former bay Hollands Diep.

The northwestern part of the estuary (around Hook of Holland), is still called Maasmond ("Meuse Mouth"), ignoring the fact that it now carries only water from the Rhine. This might explain the confusing naming of the various branches.

The hydrography of the current delta is characterized by the delta's main arms, disconnected arms (Hollandse IJssel, Linge, Vecht, etc.) and smaller rivers and streams. Many rivers have been closed ("dammed") and now serve as drainage channels for the numerous polders. The construction of Delta Works changed the Delta in the second half of the 20th century fundamentally. Currently Rhine water runs into the sea, or into former marine bays now separated from the sea, in five places, namely at the mouths of the Nieuwe Merwede, Nieuwe Waterway (Nieuwe Maas), Dordtse Kil, Spui and IJssel.

The Rhine-Meuse Delta is a tidal delta, shaped not only by the sedimentation of the rivers, but also by tidal currents. This meant that high tide formed a serious risk because strong tidal currents could tear huge areas of land into the sea. Before the construction of the Delta Works, tidal influence was palpable up to Nijmegen, and even today, after the regulatory action of the Delta Works, the tide acts far inland. At the Waal, the most landward tidal influence can be detected between Brakel and Zaltbommel.

Geologic history

Alpine orogeny

The Rhine flows from the Alps to the North Sea Basin. The geography and geology of its present-day watershed has been developing since the Alpine orogeny began.

In southern Europe, the stage was set in the Triassic Period of the Mesozoic Era, with the opening of the Tethys Ocean, between the Eurasian and African tectonic plates, between about 240 MBP and 220 MBP (million years before present). The present Mediterranean Sea descends from this somewhat larger Tethys sea. At about 180 MBP, in the Jurassic Period, the two plates reversed direction and began to compress the Tethys floor, causing it to be subducted under Eurasia and pushing up the edge of the latter plate in the Alpine Orogeny of the Oligocene and Miocene Periods. Several microplates were caught in the squeeze and rotated or were pushed laterally, generating the individual features of Mediterranean geography: Iberia pushed up the Pyrenees; Italy, the Alps, and Anatolia, moving west, the mountains of Greece and the islands. The compression and orogeny continue today, as shown by the ongoing raising of the mountains a small amount each year and the active volcanoes.

In northern Europe, the North Sea Basin had formed during the Triassic and Jurassic periods and continued to be a sediment receiving basin since. In between the zone of Alpine orogeny and North Sea Basin subsidence, highlands resulting from an earlier orogeny (Variscan) remained, such as the Ardennes, Eifel and Vosges.

From the Eocene onward, the ongoing Alpine orogeny caused a north–south rift system to develop in this zone. The main elements of this rift are the Upper Rhine Graben, in southwest Germany and eastern France and the Lower Rhine Embayment, in northwest Germany and the southeastern Netherlands. By the time of the Miocene, a river system had developed in the Upper Rhine Graben, that continued northward and is considered the first Rhine river. At that time, it did not yet carry discharge from the Alps; instead, the watersheds of the Rhone and Danube drained the northern flanks of the Alps.

Stream capture

The watershed of the Rhine reaches into the Alps today, but it did not start out that way. In the Miocene period, the watershed of the Rhine reached south, only to the Eifel and Westerwald hills, about 450 km (280 mi) north of the Alps. The Rhine then had the Sieg as a tributary, but not yet the Moselle. The northern Alps were then drained by the Danube.

Through stream capture, the Rhine extended its watershed southward. By the Pliocene period, the Rhine had captured streams down to the Vosges Mountains, including the Main and the Neckar. The northern Alps were then drained by the Rhone. By the early Pleistocene period, the Rhine had captured most of its current Alpine watershed from the Rhône, including the Aare. Since that time, the Rhine has added the watershed above Lake Constance (Vorderrhein, Hinterrhein, Alpenrhein; captured from the Rhône), the upper reaches of the Main, beyond Schweinfurt and the Moselle in the Vosges Mountains, captured during the Saale Ice-age from the Meuse, to its watershed.

Around 2.5 million years ago (ending 11,600 years ago) the Ice Ages began. Since approximately 600,000 years ago, six major glacial periods have occurred, in which sea level dropped as much as 120 m (390 ft) and much of the continental margins were exposed. In the Early Pleistocene, the Rhine followed a course to the northwest, through the present North Sea. During the so-called Anglian glaciation (~450,000 yr BP, marine oxygen isotope stage 12), the northern part of the present North Sea was blocked by the ice and a large lake developed, that overflowed through the English Channel. This caused the Rhine's course to be diverted through the English Channel. Since then, during glacial times, the river mouth was located offshore of Brest, France and rivers, like the River Thames and the Seine, became tributaries to the Rhine. During interglacials, when sea level rose to approximately the present level, the Rhine built deltas in what is now the Netherlands.

The most recent glacial period ran from ~74,000 (BP = Before Present), until the end of the Pleistocene (~11,600 BP). In northwest Europe, it saw two very cold phases, peaking around 70,000 BP and around 29,000–24,000 BP. The last phase slightly predates the global last ice age maximum (Last Glacial Maximum). During this time, the lower Rhine flowed roughly west through the Netherlands and extended to the southwest, through the English Channel and finally, to the Atlantic Ocean. The English Channel, the Irish Channel and most of the North Sea were dry land, mainly because sea level was approximately 120 m (390 ft) lower than today.

Most of the Rhine's current course was not under the ice during the last Ice Age; although, its source must still have been a glacier. A tundra, with Ice Age flora and fauna, stretched across middle Europe, from Asia to the Atlantic Ocean. Such was the case during the Last Glacial Maximum, ca. 22,000–14,000 yr BP, when ice-sheets covered Scandinavia, the Baltics, Scotland and the Alps, but left the space between as open tundra. Loess (wind-blown topsoil dust) arose from the south and North Sea plain settling on the slopes of the Alps, Urals and the Rhine Valley, rendering the valleys facing the prevailing winds especially fertile.

End of the last glacial period

As northwest Europe slowly began to warm from 22,000 years ago onward, frozen subsoil and expanded alpine glaciers began to thaw and fall-winter snow covers melted in spring. Much of the discharge was routed to the Rhine and its downstream extension. Rapid warming and changes of vegetation, to open forest, began about 13,000 BP. By 9000 BP, Europe was fully forested. With globally shrinking ice-cover, ocean water levels rose and the English Channel and North Sea re-inundated. Meltwater, adding to the ocean and land subsidence, drowned the former coasts of Europe transgressionally.

About 11000 years ago, the Rhine estuary was in the Strait of Dover. There remained some dry land in the southern North Sea, known as Doggerland, connecting mainland Europe to Britain. About 9000 years ago, that last divide was overtopped / dissected. Humans were already resident in the area when these events happened.

Since 7500 years ago the situation of tides, currents and land-forms has resembled the present. Rates of sea level rise dropped such that natural sedimentation by the Rhine and coastal processes widely compensate for transgression by the sea. In the southern North Sea, due to ongoing tectonic subsidence, the coastline and sea bed are sinking at the rate of about 1–3 cm (0.39–1.18 in) per century (1 meter or 39 inches in last 3000 years).

About 7000–5000 BP, a general warming encouraged migration of all former ice-locked areas, including up the Danube and down the Rhine by peoples to the east. A sudden massive expansion of the Black Sea as the Mediterranean Sea burst into it through the Bosporus may have occurred about 7500 BP.

Holocene delta

At the beginning of the Holocene (~11,700 years ago), the Rhine occupied its Late-Glacial valley. As a meandering river, it reworked its ice-age floodplain. As sea-level rise continued in the Netherlands, the formation of the Holocene Rhine-Meuse delta began (~8,000 years ago). Coeval absolute sea-level rise and tectonic subsidence have strongly influenced delta evolution. Other factors of importance to the shape of the delta are the local tectonic activities of the Peel Boundary Fault, the substrate and geomorphology, as inherited from the Last Glacial period and the coastal-marine dynamics, such as barrier and tidal inlet formations.

Since ~3000 yr BP (= years Before Present), human impact is seen in the delta. As a result of increasing land clearance (Bronze Age agriculture), in the upland areas (central Germany), the sediment load of the Rhine has strongly increased and delta growth has sped up. This has caused increased flooding and sedimentation, ending peat formation in the delta. In the geologically recent past the main process distributing sediment across the delta has been the shifting of river channels to new locations on the floodplain (termed avulsion). Over the past 6000 years, approximately 80 avulsions have occurred. Direct human impact in the delta began with the mining of peat for salt and fuel from Roman times onward. This was followed by embankment of the major distributaries and damming of minor distributaries, which took place in the 11–13th century AD. Thereafter, canals were dug, bends were straightened and groynes were built to prevent the river's channels from migrating or silting up.

At present, the branches Waal and Nederrijn-Lek discharge to the North Sea through the former Meuse estuary, near Rotterdam. The river IJssel branch flows to the north and enters the IJsselmeer (formerly the Zuider Zee), initially a brackish lagoon but a freshwater lake since 1932. The discharge of the Rhine is divided into three branches: the Waal (6/9 of total discharge), the Nederrijn – Lek (2/9 of total discharge) and the IJssel (1/9 of total discharge). This discharge distribution has been maintained since 1709 by river engineering works including the digging of the Pannerdens Kanaal and the installation, in the 20th century, of a series of weirs on the Nederrijn.

Military and cultural history

Antiquity

The Rhine was not known to Herodotus and first enters the historical period in the 1st century BC in Roman-era geography. At that time, it formed the boundary between Gaul and Germania. It is estimated that Germanic tribes have been inhabiting the area since 2000 BCE.

The Upper Rhine had been part of the areal of the late Hallstatt culture since the 6th century BC, and by the 1st century BC, the areal of the La Tène culture covered almost its entire length, forming a contact zone with the Jastorf culture, i.e. the locus of early Celtic-Germanic cultural contact.

In Roman geography, the Rhine formed the boundary between Gallia and Germania by definition; e.g. Maurus Servius Honoratus, Commentary on the Aeneid of Vergil (8.727) (Rhenus) fluvius Galliae, qui Germanos a Gallia dividit "(The Rhine is a) river of Gaul, which divides the Germanic people from Gaul."

In Roman geography, the Rhine and Hercynia Silva were considered the boundary of the civilized world; as it was a wilderness, the Romans were eager to explore it. This view is typified by Res Gestae Divi Augusti, a long public inscription of Augustus, in which he boasts of his exploits; including, sending an expeditionary fleet north of the Rheinmouth, to Old Saxony and Jutland, which he claimed no Roman had ever done before.

Augustus ordered his stepson Roman general Drusus to establish 50 military camps along the Rhine, starting the Germanic Wars in 12 BC. At this time, the plain of the Lower Rhine was the territory of the Ubii. The first urban settlement, on the grounds of what is today Downtown Cologne, along the Rhine, was Oppidum Ubiorum, which was founded in 38 BC by the Ubii. Cologne became acknowledged, as a city by the Romans in AD 50, by the name of Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium.

From the death of Augustus in AD 14 until after AD 70, Rome accepted as her Germanic frontier the water-boundary of the Rhine and upper Danube. Beyond these rivers she held only the fertile plain of Frankfurt, opposite the Roman border fortress of Moguntiacum (Mainz), the southernmost slopes of the Black Forest and a few scattered bridge-heads. The northern section of this frontier, where the Rhine is deep and broad, remained the Roman boundary until the empire fell. The southern part was different. The upper Rhine and upper Danube are easily crossed. The frontier which they form is inconveniently long, enclosing an acute-angled wedge of foreign territory between the modern Baden and Württemberg. The Germanic populations of these lands seem in Roman times to have been scanty, and Roman subjects from the modern Alsace-Lorraine had drifted across the river eastwards.

The Romans kept eight legions in five bases along the Rhine. The number was reduced to four as more units were moved to the Danube. The actual number of legions present at any base or in all, depended on whether a state or threat of war existed. Between about AD 14 and 180, the assignment of legions was as follows:

For the army of Germania Inferior, two legions at Vetera (Xanten), I Germanica and XX Valeria (Pannonian troops); two legions at oppidum Ubiorum ("town of the Ubii"), which was renamed to Colonia Agrippina, descending to Cologne, V Alaudae, a Celtic legion recruited from Gallia Narbonensis and XXI, possibly a Galatian legion from the other side of the empire.

For the army of Germania Superior: one legion, II Augusta, at Argentoratum (Strasbourg); and one, XIII Gemina, at Vindonissa (Windisch). Vespasian had commanded II Augusta, before he became emperor. In addition, were a double legion, XIV and XVI, at Moguntiacum (Mainz).

The two original military districts of Germania Inferior and Germania Superior, came to influence the surrounding tribes, who later respected the distinction in their alliances and confederations. For example, the upper Germanic peoples combined into the Alemanni. For a time, the Rhine ceased to be a border, when the Franks crossed the river and occupied Roman-dominated Celtic Gaul, as far as Paris.

Germanic tribes crossed the Rhine in the Migration period, by the 5th century establishing the kingdoms of Francia on the Lower Rhine, Burgundy on the Upper Rhine and Alemannia on the High Rhine. This "Germanic Heroic Age" is reflected in medieval legend, such as the Nibelungenlied which tells of the hero Siegfried killing a dragon on the Drachenfels (Siebengebirge) ("dragons rock"), near Bonn at the Rhine and of the Burgundians and their court at Worms, at the Rhine and Kriemhild's golden treasure, which was thrown into the Rhine by Hagen.

Medieval and modern history

By the 6th century, the Rhine was within the borders of Francia. In the 9th, it formed part of the border between Middle and Eastern Francia, but in the 10th century, it was fully within the Holy Roman Empire, flowing through Swabia, Franconia and Lower Lorraine. The mouths of the Rhine, in the county of Holland, fell to the Burgundian Netherlands in the 15th century; Holland remained contentious territory throughout the European wars of religion and the eventual collapse of the Holy Roman Empire, when the length of the Rhine fell to the First French Empire and its client states. The Alsace on the left banks of the Upper Rhine was sold to Burgundy by Archduke Sigismund of Austria in 1469 and eventually fell to France in the Thirty Years' War. The numerous historic castles in Rhineland-Palatinate attest to the importance of the river as a commercial route.

Since the Peace of Westphalia, the Upper Rhine formed a contentious border between France and Germany. Establishing "natural borders" on the Rhine was a long-term goal of French foreign policy, since the Middle Ages, though the language border was – and is – far more to the west. French leaders, such as Louis XIV and Napoleon Bonaparte, tried with varying degrees of success to annex lands west of the Rhine. The Confederation of the Rhine was established by Napoleon, as a French client state, in 1806 and lasted until 1814, during which time it served as a significant source of resources and military manpower for the First French Empire. In 1840, the Rhine crisis, prompted by French prime minister Adolphe Thiers's desire to reinstate the Rhine as a natural border, led to a diplomatic crisis and a wave of nationalism in Germany.

The Rhine became an important symbol in German nationalism during the formation of the German state in the 19th century (see Rhine romanticism).

- The song Die Wacht am Rhein, which almost became a national anthem.

- Das Rheingold – inspired by the Nibelungenlied, the Rhine is one of the settings for the first opera of Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen. The action of the epic opens and ends underneath the Rhine, where three Rheinmaidens swim and protect a hoard of gold.

- The Loreley/Lorelei is a rock on the eastern bank of the Rhine, that is associated with several legendary tales, poems and songs. The river spot has a reputation for being a challenge for inexperienced navigators.

At the end of World War I, the Rhineland was subject to the Treaty of Versailles. This decreed that it would be occupied by the allies, until 1935 and after that, it would be a demilitarized zone, with the German army forbidden to enter. The Treaty of Versailles and this particular provision, in general, caused much resentment in Germany. The Allies' troops left the Rhineland in 1930 and, following the rise to power of Adolf Hitler, the German army re-occupied it in 1936, which proved an enormously popular action in Germany. Although the Allies could probably have prevented the reoccupation, Britain and France were not inclined to do so, a feature of their policy of appeasement to Hitler.

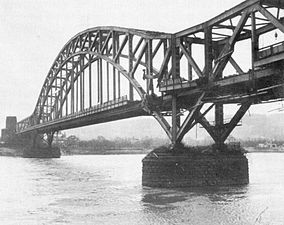

In World War II, it was recognized that the Rhine would present a formidable natural obstacle to the invasion of Germany, by the Western Allies. The Rhine bridge at Arnhem, immortalized in the book, A Bridge Too Far and the film, was a central focus of the battle of Arnhem, during the failed Operation Market Garden of September 1944. The bridges at Nijmegen, over the Waal distributary of the Rhine, were also an objective of Operation Market Garden. In a separate operation, the Ludendorff Bridge, crossing the Rhine at Remagen, became famous, when U.S. forces were able to capture it intact – much to their own surprise – after the Germans failed to demolish it. This also became the subject of a film, The Bridge at Remagen. Seven Days to the River Rhine was a Warsaw Pact war plan for an invasion of Western Europe during the Cold War.

Until 1932, the generally accepted length of the Rhine was 1,230 kilometers (760 mi). In 1932 the German encyclopedia Knaurs Lexikon stated the length as 1,320 kilometers (820 mi), presumably a typographical error. After this number was placed into the authoritative Brockhaus Enzyklopädie, it became generally accepted and found its way into numerous textbooks and official publications. The error was discovered in 2010, and the Dutch Rijkswaterstaat confirms the length at 1,232 kilometers (766 miles).

Lists of features

Cities on the Rhine

|

Large cities that are situated on the Rhine: Switzerland: France: Germany:

Netherlands: |

Smaller cities that are situated on the Rhine: Switzerland: Liechtenstein: Germany:

Netherlands:

|

Countries and borders

During its course from the Alps to the North Sea, the Rhine passes through four countries and constitutes six different country borders. On the various parts:

- the Anterior Rhine lies entirely within Switzerland, while at least one tributary to Posterior Rhine, Reno di Lei originates in Italy, but is not considered a part of the Rhine proper.

- the Alpine Rhine flows within Switzerland till Sargans, from which it becomes the border between Switzerland (to the west) and Liechtenstein (to the east) until Oberriet, and the river never flows within Liechtenstein. It then becomes the border between Switzerland (to the west) and Austria (to the east) until Diepoldsau where the modern and straight course enters Switzerland, while the original course Alter Rhein makes a bend to the east and continues as the Swiss-Austrian border until the confluence at Widnau. From here the river continues as the border until Lustenau, where the modern and straight course enters Austria (the only part of the river that flows within Austria), while the original course makes a bend to the west and continues as the border, until both courses enter Lake Constance.

- the first half of Seerhein, between the upper and lower body of Lake Constance, flows within Germany (and the city of Konstanz), while the second is the German (to the north) – Swiss (to the south) frontier.

- the first parts of the High Rhine, from Lake Constance to Altholz, the river alternates flowing within Switzerland and being the German-Swiss frontier (three times each). From Altholz the river is the German-Swiss border until Basel, where it enters Switzerland for the last time.

- the Upper Rhine is the border between France (to the west) and Switzerland (to the east) for a short distance, from Basel to Hunningue. Here it becomes the Franco (to the west) – German (to the east) frontier until Au am Rhein. Hence, the main course of the Rhine never flows within France, although some river canals do. From Au am Rhein the river flows within Germany.

- the Middle Rhine flows entirely within Germany.

- the Lower Rhine flows within Germany until Emmerich am Rhein, where it becomes the border between The Netherlands (to the north) and Germany (to the south). At Millingen aan de Rijn the river enters the Netherlands.

- all parts of the Delta Rhein flows within the Netherlands until they enter the North Sea, IJsselmeer (IJssel) or Haringvliet (Waal) at the Dutch coast.

Bridges

Former distributaries

Order: panning north to south through the Western Netherlands:

- Vecht (Utrecht) (minor channel in Roman times, flowing into former Zuider Zee lagoon)

- Kromme Rijn – Oude Rijn (Utrecht and South Holland) (main channel in Roman times, dammed in the 12th century)

- Hollandse IJssel (formed after Roman times, dammed in the 13th century AD)

- Linge (big channel in Roman times, dammed in the 14th century AD)

- De Biesbosch-area (initiated by AD 1421–1424 storm surges and river floods, by-passed since the digging of Nieuwe Merwede canal in AD 1904)

Canals

Order: upstream to downstream:

- Rhine–Main–Danube Canal – southeastern Germany

- Grand Canal d'Alsace – eastern France

- Rhine-Herne Canal – northwest Germany, connection to the Dortmund-Ems Canal and the Mittellandkanal

- Maas-Waal Canal – eastcentral Netherlands

- Amsterdam-Rhine Canal – central Netherlands

- Scheldt-Rhine Canal – southwest Netherlands

- Canal of Drusus

See also

- Mainz (1929 ship)

- Central Commission for Navigation on the Rhine

- EV15 The Rhine Cycle Route

- Köln-Düsseldorfer

- Piz Lunghin (triple watershed: Po–Rhine–Danube)

- Witenwasserenstock (triple watershed: Rhone–Rhine–Po)

- List of old waterbodies of the Rhine

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ The Rhine only has an official length scale (Rheinkilometer) downstream of Konstanz. Its full length is subject to the definition of the Alpine Rhine. In 2010, there were media reports to the effect that the length of the Rhine had been consistently over-stated in 20th-century encyclopedias, and upon request by journalists, the Dutch Rijkswaterstaat gave a length of 1,232 kilometers (766 mi).

- ^ German: Rhein [ʁaɪn] ; French: Rhin [ʁɛ̃] ; Dutch: Rijn [rɛin] ; Walloon: Rén [ʀẽ] ; Limburgish: Rien; Sursilvan: Rein, ריין, Sutsilvan and Surmiran: Ragn, Rumantsch Grischun, Vallader and Puter: Rain; Italian: Reno [ˈrɛːno]; Alemannic German: Rhi(n), including in Alsatian and Low Alemannic German; Ripuarian and Low Franconian: Rhing; Latin: Rhenus [ˈr̥eːnʊs].

- ^ The Rhine was not known in the Hellenistic period. It is mentioned by Cicero, In Pisonem 33.81. Strabo (1.4.3) mentions the countries "at the mouth of the Rhine" αἱ τοῦ Ῥήνου ἐκβολαί; "states that the countries "beyond the Rhine and as far as Scythia" καὶ τὰ πέραν τοῦ Ῥήνου τὰ μέχρι Σκυθῶ should be considered unknown, as Pytheas' account of remote nations cannot be trusted.

- ^ Krahe (1964) claims the hydronym as "Old European", i.e. belonging to the oldest Indo-European layer of names predating the 6th century BC (Hallstatt D) Celtic expansion.

- ^ In Albanian/Illyrian rrhedh also means to "move, flow, run". Pokorny's (1959) "3. er- : or- : r- 'to move, set in motion'" (pp. 326–32), laryngealist *h1reiH-, with an -n- suffix; Celtic reflexes: Old Irish renn "rapid", rīan "sea", Middle Irish rian "river, way". The root gives the Germanic verb rinnan (' ← *ri-nw-an) whence English run (from a causative *rannjanan, Old English eornan); Gothic rinnan "run, flow", Old English rinnan, Old Norse rinna "to run",, rinno "brook"; c.f. Sanskrit rinati "causes to flow"; Root cognates without the -n- suffix include Middle Low German ride "brook", Old English riþ "stream", Dutch ril "running stream", Latin rivus "stream", Old Church Slavonic reka "river".; see also "Rhine". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. November 2001. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ most notably the straightening of the Upper Rhine planned by Johann Gottfried Tulla, completed during 1817–1876.

- ^ The geomorphological ridge line does not necessarily coincide with the watershed, since it refers to the average altitude in a surrounding circle

- ^ The fact that the Aare contributes the larger portion of the combined volume – 51.8%, based on 1961–1990 averages – means that in hydrographical terms the Rhine could be considered a tributary of the Aare, but the greater length of the Alpine Rhine means that it retains the designation as main branch.

References

- ^ "Le Rhin" (official site) (in French). Paris, France: L'Institut National de l'Information Geographique et Forestrière IGN. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ Frijters & Leentvaar 2003.

- ^ "Rhine". Collins Dictionary (Online ed.). Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Stahl, K.; Weiler, M.; Van Tiel, M.; Kohn, I.; Hänsler, A.; Freudiger, D.; Seibert, J.; Gerlinger, K.; Moretti, G. (2022). CHR Report No. I-28: Impact of climate change on the rain, snow and glacier melt components of streamflow of the river Rhine and its tributaries (PDF). Lelystad: International Commission for the Hydrology of the Rhine Basin. p. 26. ISBN 978-90-70980-44-3.

- ^ Gerber, A. (6 July 2022). "Klimaforscher Latif: Rhein könnte bei Dürre austrocknen" [Climate researcher Latif: The Rhine could dry out in the event of a drought]. EUWID Wasser und Abwasser (in German). Gernsbach: EUWID Europäischer Wirtschaftsdienst. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ Schrader, C.; Uhlmann, B. (28 March 2010). "Der Rhein ist kürzer als gedacht – Jahrhundert-Irrtum" [The Rhine is Shorter Than Expected – The Mistake of the Century]. Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). München.

- ^ "Rhine River 90 km shorter than everyone thinks". The Local. 27 March 2010. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022.

"We checked it out and came to 1,232 kilometers," said Ankie Pannekoek, spokeswoman for the Dutch government hydrology office.

- ^ "Length of the Rhine (Update 2015) | International Commission for the Hydrology of the Rhine basin (CHR)". www.chr-khr.org.

- ^ Bosworth and Toller, An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (1898), p. 799. Sió eá ðe man hǽt Rín Orosius (ed. J. Bosworth 1859) 1.1

- ^ Rijn, Vroegmiddelnederlands Woordenboek

- ^ [1] Schweizerisches Idiotikon s.v. Rī(n) (6,994).

- ^ Krahe, H. (1964). Unsere ältesten Flussnamen [Our Oldest River Names] (in German). Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz. hdl:2027/mdp.39015055266442. OCLC 10374594.

- ^ Bosworth and Toller, An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (1898), p. 799: Rín; m.; f. The Rhine [...] O. H. Ger. Rín; m.: Icel. Rín; f.

- ^ Schädler & Weingartner 2002, Table 1, row 10-4.

- ^ "Maps of Switzerland – Swiss Confederation – GEWISS" (online map). Vorderrhein. Gewässernetz 1:2 Mio. National Map 1:200 000 (in German). Cartography by Swiss Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. Berne, Switzerland: Federal Office for the Environment FOEN. 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2016 – via map.geo.admin.ch.

- ^ Schädler & Weingartner 2002, Table 1, row 10-6.

- ^ "Maps of Switzerland – Swiss Confederation – GEWISS" (online map). Alpenrhein. Gewässernetz 1:2 Mio. National Map 1:2 Mio (in German). Cartography by Swiss Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. Berne, Switzerland: Federal Office for the Environment FOEN. 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2016 – via map.geo.admin.ch.

- ^ Schädler & Weingartner 2002, Table 1, row 10-7.

- ^ "Maps of Switzerland – Swiss Confederation – GEWISS" (online map). Lake Constance. Gewässernetz 1:200 000, Flussordnung. National Map 1:2 Mio (in German). Cartography by Swiss Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. Berne, Switzerland: Federal Office for the Environment FOEN. 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2016 – via map.geo.admin.ch.

- ^ Schädler & Weingartner 2002, Table 1, row 10-12 "Rhein–Landesgrenze (Gesamtgebiet)".

- ^ Scherrer, S.; Petrascheck, A.; Hode, H. (2006). "Extreme Hochwasser des Rheins bei Basel – Herleitung von Szenarien" [Extreme Flooding of the Rhine near Basel - Derivation of Scenarios] (PDF). Wasser Energie Luft (in German). 98 (1). Baden: Schweizerischer Wasserwirtschaftsverband: 43. ISSN 0377-905X.

- ^ Schädler & Weingartner 2002, Table 1, row 20-10.

- ^ Schädler & Weingartner 2002, Table 1, row 10-10.

- ^ "Maps of Switzerland – Swiss Confederation – GEWISS" (online map). High Rhine. Gewässernetz 1:2 Mio. National Map 1:2 Mio (in German). Cartography by Swiss Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. Berne, Switzerland: Federal Office for the Environment FOEN. 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2016 – via map.geo.admin.ch.

- ^ "Atlas der Schweiz Switzerland maps by Swiss Federal Office of Topography". Archived from the original on 9 June 2011.

- ^ "1232 - Oberalppass" (Map). Lai da Tuma (2015 ed.). 1:25 000. National Map 1:25'000. Wabern, Switzerland: Federal Office of Topography – swisstopo. 2013. ISBN 978-3-302-01232-2. Retrieved 1 March 2018 – via map.geo.admin.ch.

- ^ "1193 - Tödi" (Map). Piz Russein (2016 ed.). 1:25 000. National Map 1:25'000. Wabern, Switzerland: Federal Office of Topography – swisstopo. 2013. ISBN 978-3-302-01193-6. Retrieved 28 February 2018 – via map.geo.admin.ch.

- ^ "85 Senda Sursilvana (5 Etappen)". maps.graubuenden.ch. Archived from the original on 6 January 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ Bergmeister, U.; Kalt, L. "Geschiebeführung" [Conveyance of bedload] (in German). Lustenau: Internationale Rheinregulierung. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012.

- ^ Schädler & Weingartner 2002, Table 1, rows 10-10 and 20-10.

- ^ Cioc 2002, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Cioc 2002, p. 52.

- ^ Cioc 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Cioc 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Cioc 2002, p. 56.

- ^ Tockner, K.; Uehlinger, U.; Robinson, C. T.; Siber, R.; Tonolla, D.; Peter, F. D. (2009). "European Rivers". In Likens, G. E. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Inland Waters. Vol. 3. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 366–377. doi:10.1016/B978-012370626-3.00044-2. ISBN 978-0-12-370630-0. OCLC 319211428.

- ^ Berendsen & Stouthamer 2001

- ^ Ménot et al. 2006.

- ^ Cohen, Stouthamer & Berendsen 2002.

- ^ Hoffmann et al. 2007.

- ^ Gouw & Erkens 2007.

Bibliography

- Berendsen, H. J. A.; Stouthamer, E. (2001). Palaeogeographic Development of the Rhine-Meuse Delta, the Netherlands. Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum. ISBN 978-90-232-3695-5. OCLC 48632545.

- Blackbourn, D. (2006). The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany (1st American ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06212-0. OCLC 63244666. OL 7452134M.

- Cioc, M. (2002). The Rhine: An Eco-Biography, 1815–2000. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98254-0. JSTOR j.ctvcwndcf. OCLC 50041291.

- Cohen, K. M.; Stouthamer, E.; Berendsen, H. J. A. (February 2002). "Fluvial Deposits as a Record for Late Quaternary Neotectonic Activity in the Rhine-Meuse Delta, the Netherlands". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 81 (3–4): 389–405. Bibcode:2002NJGeo..81..389C. doi:10.1017/S0016774600022678. ISSN 0016-7746.

- Coolidge, William Augustus Brevoort; Muirhead, James Fullarton; Ashworth, Philip Arthur (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 240–242.

- Frijters, I. D.; Leentvaar, J. (2003). Rhine Case Study (PDF). Technical Documents in Hydrology, PCCP series. Vol. 17. Paris: UNESCO International Hydrological Programme. OCLC 55974122. SC/2003/WS/54.

- Gouw, M. J. P.; Erkens, G. (March 2007). "Architecture of the Holocene Rhine-Meuse delta (the Netherlands) – A result of changing external controls". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 86 (1): 23–54. Bibcode:2007NJGeo..86...23G. doi:10.1017/S0016774600021302. ISSN 0016-7746.

- Hoffmann, T.; Erkens, G.; Cohen, K.; Houben, P.; Seidel, J.; Dikau, R. (2007). "Holocene Floodplain Sediment Storage and Hillslope Erosion Within the Rhine Catchment". The Holocene. 17 (1): 105–118. Bibcode:2007Holoc..17..105H. doi:10.1177/0959683607073287. S2CID 128500289.

- Ménot, G.; Bard, E.; Rostek, F.; Weijers, J. W. H.; Hopmans, E. C.; Schouten, S.; Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. (15 September 2006). "Early Reactivation of European Rivers During the Last Deglaciation". Science. 313 (5793): 1623–1625. Bibcode:2006Sci...313.1623M. doi:10.1126/science.1130511. hdl:1874/22529. PMID 16973877. S2CID 45157193.

- Schädler, B.; Weingartner, R. (2002). "Plate 6.3: Components of the Natural Water Balance 1961–1990" (PDF). Hydrological Atlas of Switzerland.

External links

- Rhine with maps and details of navigation through the French section; places, ports and moorings, by the author of Inland Waterways of France, Imray

- Navigation details for 80 French rivers and canals (French waterways website section)

- Old maps of the Rhine, from the Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, The National Library of Israel