Ural Mountains

The mountains lie within the Ural geographical region and significantly overlap with the Ural Federal District and the Ural economic region. Their resources include metal ores, coal, and precious and semi-precious stones. Since the 18th century, the mountains have contributed significantly to the mineral sector of the Russian economy. The region is one of the largest centres of metallurgy and heavy industry production in Russia.

Etymology

As attested by Sigismund von Herberstein, in the 16th century, Russians called the Ural range by a variety of names derived from the Russian words for rock (stone) and belt. The modern Russian name for the Urals (Урал, Ural), first appearing in the 16th–17th century during the Russian conquest of Siberia, was initially applied to its southern parts and gained currency as the name of the entire range during the 18th century. It might have been borrowed from either Turkic "stone belt" (Bashkir, where the same name is used for the range), or Ob-Ugric. From the 13th century in Bashkortostan, there has been a legend about a hero named Ural who sacrificed his life for the sake of his people who then poured a stone pile over his grave, which later turned into the Ural Mountains. Possibilities include Bashkir үр "elevation; upland" and Mansi ур ала "mountain peak, top of the mountain", V.N. Tatischev believes that this oronym is set to "belt" and associates it with the Turkic verb oralu- "gird". I.G. Dobrodomov suggests a transition from Aral to Ural explained on the basis of ancient Bulgar-Chuvash dialects. Geographer E.V. Hawks believes that the name goes back to the Bashkir folklore Ural-Batyr. The Evenk geographical term era "mountain" has also been theorized. (cf also Ewenkī ürǝ-l (pl.) "mountains") Finno-Ugrist scholars consider Ural deriving from the Ostyak word urr meaning "chain of mountains". Turkologists, on the other hand, have achieved majority support for their assertion that 'ural' in Tatar means a belt, and recall that an earlier name for the range was 'stone belt'.

History

As merchants from the Middle East traded with the Bashkirs and other people living on the western slopes of the Ural as far north as Great Perm, since the 10th century, medieval mideastern geographers had been aware of the existence of the mountain range in its entirety, stretching as far as the Arctic Ocean in the north. The first Russian mention of the mountains to the east of the East European Plain is provided by the Primary Chronicle, where it describes the Novgorodian expedition to the upper reaches of the Pechora in the year 1096. During the next few centuries, the Novgorodians engaged in fur trading with the local population and collected tribute from Yugra and Great Perm, slowly expanding southwards. The city-state of Novgorod established two trade routes to the Ob River, both starting from the town of Ustyug. The rivers, Chusovaya and Belaya, were first mentioned in the chronicles of 1396 and 1468, respectively. In 1430, the town of Solikamsk (Kama Salt) was founded on the Kama at the foothills of the Ural, where salt was produced in open pans. Ivan III, the grand prince of Moscow, captured Perm, Pechora and Yugra from the declining Novgorod Republic in 1472. With the excursions of 1483 and 1499–1500 across the Ural, Moscow managed to subjugate Yugra completely. The Russians received tribute, but contact with the tribes ceased after they left.

Nevertheless, around the early 16th century, Polish geographer, Maciej of Miechów, in his influential Tractatus de duabus Sarmatiis (1517) argued that there were no mountains in Eastern Europe at all, challenging the point of view of some authors of Classical antiquity, which were popular during the Renaissance. Only after Sigismund von Herberstein in his Notes on Muscovite Affairs (1549) had reported, following Russian sources, that there are mountains behind the Pechora and identified them with the Riphean Mountains and Hyperboreans of ancient authors, did the existence of the Ural, or at least of its northern part, become firmly established in the Western geography. The Middle and Southern Ural were still largely unavailable and unknown to the Russian or Western European geographers.

In the 1550s, after the Tsardom of Russia had defeated the Khanate of Kazan and proceeded to gradually annex the lands of the Bashkirs, the Russians finally reached the southern part of the mountain chain. In 1574, they founded Ufa. The upper reaches of the Kama and Chusovaya in the Middle Ural, still unexplored, as well as parts of Transuralia still held by the hostile Siberian Khanate, were granted to the Stroganovs by several decrees of the tsar in 1558–1574. The Stroganovs land provided the staging ground for Yermak's incursion into Siberia. Yermak crossed the Ural from the Chusovaya to the Tagil around 1581. In 1597, Babinov's road was built across the Ural from Solikamsk to the valley of the Tura, where the town of Verkhoturye (Upper Tura) was founded in 1598. Customs was established in Verkhoturye shortly thereafter and the road was made the only legal connection between European Russia and Siberia for a long time. In 1648, the town of Kungur was founded at the western foothills of the Middle Ural. During the 17th century, the first deposits of iron and copper ores, mica, gemstones and other minerals were discovered in the Ural.

Iron and copper smelting works emerged. In particular, the Gumyoshevsky mine was established in 1702 at an ancient copper deposit known since Bronze Age — so-called "legendary" Copper Mountain which also produced malachite. Mining intensified particularly quickly during the reign of Peter I of Russia. In 1720–1722, he commissioned Vasily Tatishchev to oversee and develop the mining and smelting works in the Ural. Tatishchev proposed a new copper smelting factory in Yegoshikha, which would eventually become the core of the city of Perm and a new iron smelting factory on the Iset, which would become the largest in the world at the time of construction and give birth to the city of Yekaterinburg. Both factories were actually founded by Tatishchev's successor, Georg Wilhelm de Gennin, in 1723. Tatishchev returned to the Ural on the order of Empress Anna to succeed de Gennin in 1734–1737. Transportation of the output of the smelting works to the markets of European Russia necessitated the construction of the Siberian Route from Yekaterinburg across the Ural to Kungur and Yegoshikha (Perm) and further to Moscow, which was completed in 1763 and rendered Babinov's road obsolete. In 1745, gold was discovered in the Ural at Beryozovskoye and later at other deposits. It has been mined since 1747.

The first ample geographic survey of the Ural Mountains was completed in the early 18th century by the Russian historian and geographer Vasily Tatishchev under the orders of Peter I. Earlier, in the 17th century, rich ore deposits were discovered in the mountains and their systematic extraction began in the early 18th century, eventually turning the region into the largest mineral base of Russia.

One of the first scientific descriptions of the mountains was published in 1770–71. Over the next century, the region was studied by scientists from a number of countries, including Russia (geologist Alexander Karpinsky, botanist Porfiry Krylov and zoologist Leonid Sabaneyev), the United Kingdom (geologist Sir Roderick Murchison), France (paleontologist Édouard de Verneuil), and Germany (naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, geologist Alexander Keyserling). In 1845, Murchison, who had according to Encyclopædia Britannica "compiled the first geologic map of the Ural in 1841", published The Geology of Russia in Europe and the Ural Mountains with de Verneuil and Keyserling.

The first railway across the Urals had been built by 1878 and linked Perm to Yekaterinburg via Chusovoy, Kushva and Nizhny Tagil. In 1890, a railway linked Ufa and Chelyabinsk via Zlatoust. In 1896, this section became a part of the Trans-Siberian Railway. In 1909, yet another railway connecting Perm and Yekaterinburg passed through Kungur by the way of the Siberian Route. It has eventually replaced the Ufa – Chelyabinsk section as the main trunk of the Trans-Siberian railway.

The highest peak of the Ural, Mount Narodnaya, (elevation 1,895 m [6,217 ft]) was identified in 1927.

During the Soviet industrialization in the 1930s, the city of Magnitogorsk was founded in the South-Eastern Ural as a center of iron smelting and steelmaking. During the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941–1942, the mountains became a key element in Nazi planning for the territories which they expected to conquer in the USSR. Faced with the threat of having a significant part of the Soviet territories occupied by the enemy, the government evacuated many of the industrial enterprises of European Russia and Ukraine to the eastern foothills of the Ural, considered a safe place out of reach of the German bombers and troops. Three giant tank factories were established at the Uralmash in Sverdlovsk (as Yekaterinburg used to be known), Uralvagonzavod in Nizhny Tagil, and Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant in Chelyabinsk. After the war, in 1947–1948, Chum – Labytnangi railway, built with the forced labor of Gulag inmates, crossed the Polar Ural.

Mayak, 150 kilometres (93 mi) southeast of Yekaterinburg, was a center of the Soviet nuclear industry and site of the Kyshtym disaster.

Geography and topography

The Ural Mountains extend about 2,500 km (1,600 mi) from the Kara Sea to the Kazakh Steppe along the border of Kazakhstan. Vaygach Island and the island of Novaya Zemlya form a further continuation of the chain on the north. Geographically this range marks the northern part of the border between Europe and Asia. Its highest peak is Mount Narodnaya, approximately 1,895 m (6,217 ft) in elevation. Transverse faults divide the mountain chain into seven major units, each of which has its own typical pattern of mountain ridges. From north to south, these are the Pay-Khoy, Zapolyarnyy, Pripolyarnyy, Polyarnyy, Severnyy, Sredniy, Yuzhnny Ural and Mugodzhary. The average altitudes of the Urals are around 1,000–1,300 m (3,300–4,300 ft), the highest point being Narodnaya peak in the Pripolyarnyy Ural which reaches a height of 1,894 metres (6,214 ft).

By topography and other natural features, the Urals are divided, from north to south, into the Polar (or Arctic), Nether-Polar (or Sub-Arctic), Northern, Central and Southern parts.

Polar Ural

The Polar Urals extend for about 385 kilometers (239 mi) from Mount Konstantinov Kamen in the north to the river Khulga in the south; they have an area of about 25,000 km (9,700 sq mi) and a strongly dissected relief. The maximum height is 1,499 m (4,918 ft) at Mount Payer and the average height is 1,000 to 1,100 m (3,300 to 3,600 ft).

The mountains of the Polar Ural have exposed rock with sharp ridges, though flattened or rounded tops are also found.

Nether-polar Ural

The Nether-Polar Ural are higher, and up to 150 km (93 mi) wider than the Polar Urals. They include the highest peaks of the range: Mount Narodnaya (1,895 m (6,217 ft)), Mount Karpinsky (1,878 m (6,161 ft)) and Manaraga (1,662 m (5,453 ft)). They extend for more than 225 km (140 mi) south to the Shchugor. The many ridges are sawtooth shaped and dissected by river valleys. Both Polar and Nether-Polar Urals are typically Alpine; they bear traces of Pleistocene glaciation, along with permafrost and extensive modern glaciation, including 143 extant glaciers.

Northern Ural

The Northern Ural consist of a series of parallel ridges up to 1,000–1,200 m (3,300–3,900 ft) in height and longitudinal hollows. They are elongated from north to south and stretch for about 560 km (350 mi) from the river Usa. Most of the tops are flattened, but those of the highest mountains, such as Telposiz, 1,617 m (5,305 ft) and Konzhakovsky Stone, 1,569 m (5,148 ft) have a dissected topography. Intensive weathering has produced vast areas of eroded stone on the mountain slopes and summits of the northern areas.

Central Ural

The Central Ural are the lowest part of the Ural, with smooth mountain tops, the highest mountain being 994 m (3,261 ft) (Basegi); they extend south from the river Ufa.

Southern Ural

The relief of the Southern Ural is more complex, with numerous valleys and parallel ridges directed south-west and meridionally. The range includes the Ilmensky Mountains separated from the main ridges by the Miass. The maximum height is 1,640 m (5,380 ft) (Mount Yamantau) and the width reaches 250 km (160 mi). Other notable peaks lie along the Iremel mountain ridge (Bolshoy Iremel and Maly Iremel) and Nurgush. The Southern Urals extend some 550 km (340 mi) up to the sharp westward bend of the river Ural and terminate in the Guberlin Mountains and finally in the wide Mughalzhar Hills.

|

|

|

|

| Mountain formation near Saranpaul, Nether-Polar Urals | Rocks in a river, Nether-Polar Urals | Big Iremel Mountain | Entry to Ignateva Cave, South Urals |

Geology

The Urals are among the world's oldest extant mountain ranges. Some have estimated the age to be 250 to 300 million years, the elevation of the mountains is unusually high. They formed during the Uralian orogeny due to the collision of the eastern edge of the supercontinent Laurasia with the young and rheologically weak continent of Kazakhstania, which now underlies much of Kazakhstan and West Siberia west of the Irtysh, and intervening island arcs. The collision lasted nearly 90 million years in the late Carboniferous – early Triassic. Unlike the other major orogens of the Paleozoic (Appalachians, Caledonides, Variscides), the Urals have not undergone post-orogenic extensional collapse and are unusually well preserved for their age, being underlaid by a pronounced crustal root. East and south of the Urals much of the orogen is buried beneath later Mesozoic and Cenozoic sediments. The adjacent Pay-Khoy Ridge to the north and Novaya Zemlya are not a part of the Uralian orogen and formed later.

Many deformed and metamorphosed rocks, mostly of Paleozoic age, surface within the Urals. The sedimentary and volcanic layers are folded and faulted. The sediments to the west of the Ural Mountains are formed of limestone, dolomite and sandstone left from ancient shallow seas. The eastern side is dominated by basalts.

The western slope of the Ural Mountains has predominantly karst topography, especially in the Sylva basin, which is a tributary of the Chusovaya. It is composed of severely eroded sedimentary rocks (sandstones and limestones) that are about 350 million years old. There are many caves, sinkholes and underground streams. The karst topography is much less developed on the eastern slopes. The eastern slopes are relatively flat, with some hills and rocky outcrops and contain alternating volcanic and sedimentary layers dated to the middle Paleozoic Era. Most high mountains consist of weather-resistant rocks such as quartzite, schist and gabbro that are between 395 and 570 million years old. The river valleys are underlain by limestone.

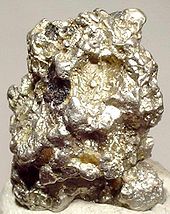

The Ural Mountains contain about 48 species of economically valuable ores and minerals. Eastern regions are rich in chalcopyrite, nickel oxide (e. g. Serov nickel deposit), gold, platinum, chromite and magnetite ores, as well as in coal (Chelyabinsk Oblast), bauxite, talc, fireclay and abrasives. The Western Urals contain deposits of coal, oil, natural gas (Ishimbay and Krasnokamsk areas) and potassium salts. Both slopes are rich in bituminous coal and lignite, and the largest deposit of bituminous coal is in the north (Pechora field). The specialty of the Urals is precious and semi-precious stones, such as emerald, amethyst, aquamarine, jasper, rhodonite, malachite and diamond. Some of the deposits, such as the magnetite ores at Magnitogorsk, are already nearly depleted.

|

|

|

|

| Andradite | Beryl | Platinum | Quartz |

Rivers and lakes

Many rivers originate in the Ural Mountains. The western slopes south of the border between the Komi Republic and Perm Krai and the eastern slopes south of approximately 54°30'N drain into the Caspian Sea via the Kama and Ural basins. The tributaries of the Kama include the Vishera, Chusovaya, and Belaya and originate on both the eastern and western slopes. The rest of the Urals drain into the Arctic Ocean, mainly via the Pechora basin in the west, which includes the Ilych, Shchugor, and the Usa, and via the Ob basin in the east, which includes the Tobol, Tavda, Iset, Tura and Severnaya Sosva. The rivers are frozen for more than half the year. Generally, the western rivers have higher flow volume than the eastern ones, especially in the Northern and Nether-Polar regions. Rivers are slower in the Southern Urals. This is because of low precipitation and the relatively warm climate resulting in less snow and more evaporation.

The mountains contain a number of deep lakes. The eastern slopes of the Southern and Central Urals have most of these, among the largest of which are the Uvildy, Itkul, Turgoyak, and Tavatuy lakes. The lakes found on the western slopes are less numerous and also smaller. Lake Bolshoye Shchuchye, the deepest lake in the Polar Urals, is 136 meters (446 ft) deep. Other lakes, too, are found in the glacial valleys of this region. Spas and sanatoriums have been built to take advantage of the medicinal muds found in some of the mountain lakes.

Climate

The climate of the Urals is continental. The mountain ridges, elongated from north to south, effectively absorb sunlight thereby increasing the temperature. The areas west of the Ural Mountains are 1–2 °C (1.8–3.6 °F) warmer in winter than the eastern regions because the former are warmed by Atlantic winds whereas the eastern slopes are chilled by Siberian air masses. The average January temperatures increase in the western areas from −20 °C (−4 °F) in the Polar to −15 °C (5 °F) in the Southern Urals and the corresponding temperatures in July are 10 and 20 °C (50 and 68 °F). The western areas also receive more rainfall than the eastern ones by 150–300 mm (5.9–11.8 in) per year. This is because the mountains trap clouds from the Atlantic Ocean. The highest precipitation, approximately 1,000 mm (39 in), is in the Northern Urals with up to 1,000 cm (390 in) snow. The eastern areas receive from 500–600 mm (20–24 in) in the north to 300–400 mm (12–16 in) in the south. Maximum precipitation occurs in the summer: the winter is dry because of the Siberian High.

Flora

The landscapes of the Urals vary with both latitude and longitude and are dominated by forests and steppes. The southern area of the Mughalzhar Hills is a semidesert. Steppes lie mostly in the southern and especially south-eastern Urals. Meadow steppes have developed on the lower parts of mountain slopes and are covered with zigzag and mountain clovers, Serratula gmelinii, dropwort, meadow-grass and Bromus inermis, reaching the height of 60–80 centimetres (24–31 in). Much of the land is cultivated. To the south, the meadow steppes become more sparse, dry and low. The steep gravelly slopes of the mountains and hills of the eastern slopes of the Southern Urals are mostly covered with rocky steppes. River valleys contain willow, poplar and caragana shrubs.

Forest landscapes of the Urals are diverse, especially in the southern part. The western areas are dominated by dark coniferous taiga forests which change to mixed and deciduous forests in the south. The eastern mountain slopes have light coniferous taiga forests. The Northern Urals are dominated by conifers, namely Siberian fir, Siberian pine, Scots pine, Siberian spruce, Norway spruce and Siberian larch, as well as by silver and downy birches. The forests are much sparser in the Polar Urals. Whereas in other parts of the Ural Mountains they grow up to an altitude of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), in the Polar Urals the tree line is at 250–400 metres (820–1,310 ft). The low polar forests are mixed with swamps, lichens, bogs and shrubs. Dwarf birch, mosses and berries (blueberry, cloudberry, black crowberry, etc.) are abundant. The forests of the Southern Urals are the most diverse in composition: here, together with coniferous forests are also abundant broadleaf tree species such as English oak, Norway maple and elm. The Virgin Komi Forests in the northern Urals are recognized as a World Heritage site.

Fauna

The forests of Urals are inhabited by animals typical of Eurosiberia, such as elk, brown bear, fox, wolf, wolverine, lynx, squirrel, Siberian chipmunk, flying squirrel, reindeer and sable (north only). The fauna of Polar Urals also includes species like Arctic Fox and lemmings. Because of the easy accessibility of the mountains there are no specifically mountainous species. In the Central Urals, one can see a rare mixture of sable and pine marten named kidus. In the Southern Urals, badger and black polecat are common. Reptiles and amphibians live mostly in the Southern and Central Ural and are represented by the common viper, lizards and grass snakes. Bird species of Northern, Middle and South Urals are represented by Western Capercaillie, black grouse, hazel grouse, spotted nutcracker, Siberian Jay, Common and Oriental cuckoos. Unlike mammals, the highest peaks and plateaus of Northern and Southern Urals are inhabited by some mountainous or tundra avian species, like Golden Plover, Dotterel, Ptarmigan and Willow Grouse, in Polar Urals also by Rough-legged Buzzard and Snowy Owl.

The steppes of the Southern Urals are dominated by hares and rodents such as hamsters, susliks, and jerboa. There are many birds of prey such as lesser kestrel and buzzards.

Ecology

The continuous and intensive economic development of the last centuries has affected the fauna, and wildlife is much diminished around all industrial centers. During World War II, hundreds of factories were evacuated from Western Russia before the German occupation, flooding the Urals with industry. The conservation measures include establishing national wildlife parks. There are nine strict nature reserves in the Urals: the Ilmen, the oldest one, mineralogical reserve founded in 1920 in Chelyabinsk Oblast, Pechora-Ilych in the Komi Republic, Bashkir and its former branch Shulgan-Tash in Bashkortostan, Visim in Sverdlovsk Oblast, Southern Ural in Bashkortostan, Basegi in Perm Krai, Vishera in Perm Krai and Denezhkin Kamen in Sverdlovsk Oblast.

The area has also been severely damaged by the plutonium-producing facility Mayak, opened in Chelyabinsk-40 (later called Chelyabinsk-65, Ozyorsk), in the Southern Ural, after World War II. Its plants went into operation in 1948 and, for the first ten years, dumped unfiltered radioactive waste into the river Techa and Lake Karachay. In 1990, efforts were underway to contain the radiation in one of the lakes, which was estimated at the time to expose visitors to 500 millirem per day. As of 2006, 500 mrem in the natural environment was the upper limit of exposure considered safe for a member of the general public in an entire year (though workplace exposure over a year could exceed that by a factor of 10). Over 23,000 km (8,900 sq mi) of land were contaminated in 1957 from a storage tank explosion, only one of several serious accidents that further polluted the region. The 1957 accident expelled 20 million curies of radioactive material, 90% of which settled into the land immediately around the facility. Although some reactors of Mayak were shut down in 1987 and 1990, the facility keeps producing plutonium.

Cultural significance

The Urals have been viewed by Russians as a "treasure box" of mineral resources, which were the basis for its extensive industrial development. In addition to iron and copper, the Urals were a source of gold, malachite, alexandrite, and other gems such as those used by the court jeweller Fabergé. As Russians in other regions gather mushrooms or berries, Uralians gather mineral specimens and gems. Dmitry Mamin-Sibiryak (1852–1912) and Pavel Bazhov (1879–1950), as well as Aleksey Ivanov and Olga Slavnikova, post-Soviet writers, have written of the region.

The region served as a military stronghold during Peter the Great's Great Northern War with Sweden, during Stalin's rule when the Magnitogorsk Metallurgical Complex was built and Russian industry relocated to the Urals during the Nazi advance at the beginning of World War II, and as the center of the Soviet nuclear industry during the Cold War. Extreme levels of air, water, and radiological contamination and pollution by industrial wastes resulted. Population exodus followed, and economic depression at the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union, but in post-Soviet times additional mineral exploration, particularly in the northern Urals, has been productive and the region has attracted industrial investment.

Gallery

-

Mount Iremel

-

Mount Iremel

-

Mount Iremel peak

-

Mount Yamantau

-

View from mount Yamantau second peak (Bolshaya Yamantau)

-

Forest around mount Yamantau

-

View of the two-peak mount Taganay

-

Mount Otkliknoy Greben

-

Taganay national park

-

Sunrise on Taganay

See also

- Yugyd Va National Park

- Dyatlov Pass incident

- East Ural Radioactive Trace

- Idel-Ural State

- Pangea

- Research Range

- Ural Mountains in Nazi planning

- Magnetic Mountain

Russia portal

Russia portal Siberia portal

Siberia portal

Notes

- ^ Russian: Уральские горы, romanized: Uraljskije gory, IPA: [ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ]; Bashkir: Урал тауҙары, romanized: Ural tawźarı, IPA: [ʊˈrɑɫ tʰɑwðɑˈrɤ]; Kazakh: Орал таулары, romanized: Oral taulary, IPA: [woˈrɑɫ tʰɑwɫɑˈrə]

References

- ^ Ural Mountains Archived 29 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica on-line

- ^ Embleton, Clifford (2016). Geomorphology of Europe. Macmillan Education UK. p. 404. ISBN 9781349173464.

- ^ Russian Regional Economic and Business Atlas. International Business Publications. August 2013. p. 42. ISBN 9781577510291.

- ^ Koryakova, Ludmila; Epimakhov, Andrey (2014). The Urals and Western Siberia in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Cambridge University Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-1-139-46165-8.

- ^ Фасмер, Макс. Этимологический словарь русского языка

- ^ "Урал (географич.) (Ural (geographical))". Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ Koriakova, Ludmila; Epimakhov, Andrei (2007). The Urals and Western Siberia in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Cambridge University Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-521-82928-1.

- ^ Ural, toponym Archived 12 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine Chlyabinsk Encyclopedia (in Russian)

- ^ "What is the Urals". Survinat. 30 October 2014. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch; Bealby, John Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 786–787.

... the name of Urals (Uraly)—derived either from the Ostyak urr (chain of mountains) or from the Turkish aral-tau or oral-tau...

- ^ Dukes, Paul (2015). A History of the Urals: Russia's Crucible from Early Empire to the Post-Soviet Era. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4725-7379-7.

- ^ Naumov 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Naumov 2006, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Geological Society of London (1894). The Quarterly journal of the Geological Society of London. The Society. p. 53.

- ^ cf. Murchison, Roderick Impey; de Verneuil, Edouard; Keyserling, Alexander (1845). The Geology of Russia in Europe and the Ural Mountains. John Murray.

- ^ "Climbing the highest mountains of the Nether-Polar Ural ::: Ural Expedition & Tours". welcome-ural.ru.

- ^ Podvig, Pavel; Bukharin, Oleg; von Hippel, Frank (2004). Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces. MIT Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-262-66181-2.

- ^ Paine, Christopher (22 July 1989). "Military reactors go on show to American visitors". New Scientist. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ American Chemical Society (2006). Chemistry in the Community: ChemCom. Macmillan. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-7167-8919-2.

- ^ "Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: Science and Public Affairs. Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc.: 25 May 1991. ISSN 0096-3402.

- ^ Brown, D.; Echtler, H. (2005). "The Urals". In Selley, R. C.; Cocks, L. R. M.; Plimer, I. R. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Geology. Vol. 2. Elsevier. pp. 86–95. ISBN 978-0126363807.

- ^ Cocks, L. R. M.; Torsvik, T. H. (2006). "European geography in a global context from the Vendian to the end of the Palaeozoic". In Gee, D. G.; Stephenson, R. A. (eds.). European Lithosphere Dynamics (PDF). Vol. 32. Geological Society of London. pp. 83–95. ISBN 978-1862392120. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2009.

- ^ Puchkov, V. N. (2009). "The evolution of the Uralian orogen". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 327 (1): 161–195. Bibcode:2009GSLSP.327..161P. doi:10.1144/SP327.9. S2CID 129439058.

- ^ Brown, D.; Juhlin, C.; Ayala, C.; Tryggvason, A.; Bea, F.; Alvarez-Marron, J.; Carbonell, R.; Seward, D.; Glasmacher, U.; Puchkov, V.; Perez-Estaun, sexbombA. (2008). "Mountain building processes during continent–continent collision in the Uralides". Earth-Science Reviews. 89 (3–4): 177. Bibcode:2008ESRv...89..177B. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2008.05.001.

- ^ Leech, M. L. (2001). "Arrested orogenic development: Eclogitization, delamination, and tectonic collapse" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 185 (1–2): 149–159. Bibcode:2001E&PSL.185..149L. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(00)00374-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Scarrow, J. H.; Ayala, C.; Kimbell, G. S. (2002). "Insights into orogenesis: Getting to the root of a continent-ocean-continent collision, Southern Urals, Russia" (PDF). Journal of the Geological Society. 159 (6): 659. Bibcode:2002JGSoc.159..659S. doi:10.1144/0016-764901-147. S2CID 17694777. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Davis, W.M. (1898). "The Ural mountains". Science. 7 (173): 563–564. doi:10.1126/science.7.173.563

- ^ Производство плутония с ПО "Маяк" на Сибирский химкомбинат перенесено не будет Archived 23 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine [Plutonium production will not be transferred from Mayak], obzor.westsib.ru, 25 March 2010 (in Russian)

- ^ Givental, E. (2013). "Three Hundred Years of Glory and Gloom: The Urals Region of Russia in Art and Reality". SAGE Open. 3 (2): 215824401348665. doi:10.1177/2158244013486657.

Bibliography

- Naumov, Igor V. (22 November 2006). The History of Siberia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-20703-9.

External links

- Peakbagger.com page on the Ural Mountains

- Ural Expeditions & Tours page on the five parts of the Ural Mountains

- Robert B. Hayes, "Some Mathematical and Geophysical Considerations in Radioisotope Dating Applications," Nuclear Technology 197 (2017): 209–218, doi:10.13182/NT16-98.