Wright Brothers

The brothers' breakthrough invention was their creation of a three-axis control system, which enabled the pilot to steer the aircraft effectively and to maintain its equilibrium. Their system of aircraft controls made fixed-wing powered flight possible and remains standard on airplanes of all kinds. Their first U.S. patent did not claim invention of a flying machine, but rather a system of aerodynamic control that manipulated a flying machine's surfaces. From the beginning of their aeronautical work, Wilbur and Orville focused on developing a reliable method of pilot control as the key to solving "the flying problem". This approach differed significantly from other experimenters of the time who put more emphasis on developing powerful engines. Using a small home-built wind tunnel, the Wrights also collected more accurate data than any before, enabling them to design more efficient wings and propellers.

The brothers gained the mechanical skills essential to their success by working for years in their Dayton, Ohio-based shop with printing presses, bicycles, motors, and other machinery. Their work with bicycles, in particular, influenced their belief that an unstable vehicle such as a flying machine could be controlled and balanced with practice. This was a trend, as many other aviation pioneers were also dedicated cyclists and involved in the bicycle business in various ways. From 1900 until their first powered flights in late 1903, the brothers conducted extensive glider tests that also developed their skills as pilots. Their shop mechanic Charles Taylor became an important part of the team, building their first airplane engine in close collaboration with the brothers.

The Wright brothers' status as inventors of the airplane has been subject to numerous counter-claims. Much controversy persists over the many competing claims of early aviators. Edward Roach, historian for the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park, argues that the Wrights were excellent self-taught engineers who could run a small company well, but did not have the business skills or temperament necessary to dominate the rapidly growing aviation industry at the time.

Childhood

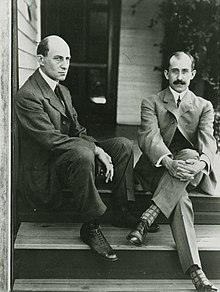

Wilbur and Orville Wright were two of seven children born to Milton Wright (1828–1917), a clergyman of English and Dutch ancestry, and Susan Catherine Koerner (1831–1889), of German and Swiss ancestry. Milton Wright's mother, Catherine Reeder, was descended from the progenitor of the Vanderbilt family – one of America's richest families – and the Huguenot Gano family of New Rochelle, New York. Wilbur and Orville were the 3rd great nephews of John Gano, the Revolutionary War Brigade Chaplain, who allegedly baptized President George Washington. Through John Gano they were 5th cousins 1 time removed of billionaire and aviator Howard Hughes. Wilbur was born near Millville, Indiana, in 1867; Orville in Dayton, Ohio, in 1871.

The brothers never married. The other Wright siblings were Reuchlin (1861–1920), Lorin (1862–1939), Katharine (1874–1929), and twins Otis and Ida (born 1870, died in infancy). The direct paternal ancestry goes back to a Samuel Wright (b. 1606 in Essex, England) who sailed to America and settled in Massachusetts in 1636.

None of the Wright children had middle names. Instead, their father tried hard to give them distinctive first names. Wilbur was named for Willbur Fisk and Orville for Orville Dewey, both clergymen that Milton Wright admired. They were "Will" and "Orv" to their friends and in Dayton, their neighbors knew them simply as "the Bishop's kids", or "the Bishop's boys".

Because of their father's position as a bishop in the Church of the United Brethren in Christ, he traveled often and the Wrights frequently moved – twelve times before finally returning permanently to Dayton in 1884. In elementary school, Orville was given to mischief and was once expelled. In 1878, when the family lived in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, their father brought home a toy helicopter for his two younger sons. The device was based on an invention of French aeronautical pioneer Alphonse Pénaud. Made of paper, bamboo and cork with a rubber band to twirl its rotor, it was about 1 ft (30 cm) long. Wilbur and Orville played with it until it broke, and then built their own. In later years, they pointed to their experience with the toy as the spark of their interest in flying.

Early career and research

Both brothers attended high school, but did not receive diplomas. The family's abrupt move in 1884 from Richmond, Indiana, to Dayton, Ohio, where the family had lived during the 1870s, prevented Wilbur from receiving his diploma after finishing four years of high school. The diploma was awarded posthumously to Wilbur on April 16, 1994, which would have been his 127th birthday. In late 1885 or early 1886, while playing an ice-skating game with friends Wilbur was struck in the face by a hockey stick by Oliver Crook Haugh, who later became a serial killer. Wilbur lost his front teeth. He had been vigorous and athletic until then, and although his injuries did not appear especially severe, he became withdrawn. He had planned to attend Yale. Instead, he spent the next few years largely housebound. During this time he cared for his mother, who was terminally ill with tuberculosis, read extensively in his father's library and ably assisted his father during times of controversy within the Brethren Church, but also expressed unease over his own lack of ambition.

Orville dropped out of high school after his junior year to start a printing business in 1889, having designed and built his own printing press with Wilbur's help. Wilbur joined the print shop, and in March the brothers launched a weekly newspaper, the West Side News. Subsequent issues listed Orville as publisher and Wilbur as editor on the masthead. In April 1890 they converted the paper to a daily, The Evening Item, but it lasted only four months. They then focused on commercial printing. One of their clients was Orville's friend and classmate, Paul Laurence Dunbar, who rose to international acclaim as a ground-breaking African-American poet and writer. For a brief period the Wrights printed the Dayton Tattler, a weekly newspaper that Dunbar edited.

Capitalizing on the national bicycle craze (spurred by the invention of the safety bicycle and its substantial advantages over the penny-farthing design), in December 1892 the brothers opened a repair and sales shop (the Wright Cycle Exchange, later the Wright Cycle Company) and in 1896 began manufacturing their own brand. They used this endeavor to fund their growing interest in flight. In the early or mid-1890s they saw newspaper or magazine articles and probably photographs of the dramatic glides by Otto Lilienthal in Germany.

1896 brought three important aeronautical events. In May, Smithsonian Institution Secretary Samuel Langley successfully flew an unmanned steam-powered fixed-wing model aircraft. In mid-year, Chicago engineer and aviation authority Octave Chanute brought together several men who tested various types of gliders over the sand dunes along the shore of Lake Michigan. In August, Lilienthal was killed in the plunge of his glider. These events lodged in the minds of the brothers, especially Lilienthal's death. The Wright brothers later cited his death as the point when their serious interest in flight research began.

Wilbur said, "Lilienthal was without question the greatest of the precursors, and the world owes to him a great debt." In May 1899 Wilbur wrote a letter to the Smithsonian Institution requesting information and publications about aeronautics. Drawing on the work of Sir George Cayley, Chanute, Lilienthal, Leonardo da Vinci, and Langley, they began their mechanical aeronautical experimentation that year.

The Wright brothers always presented a unified image to the public, sharing equally in the credit for their invention. Biographers note that Wilbur took the initiative in 1899 and 1900, writing of "my" machine and "my" plans before Orville became deeply involved when the first person singular became the plural "we" and "our". Author James Tobin asserts, "it is impossible to imagine Orville, bright as he was, supplying the driving force that started their work and kept it going from the back room of a store in Ohio to conferences with capitalists, presidents, and kings. Will did that. He was the leader, from the beginning to the end."

Ideas about control

Despite Lilienthal's fate, the brothers favored his strategy: to practice gliding in order to master the art of control before attempting motor-driven flight. The death of British aeronaut Percy Pilcher in another hang gliding crash in October 1899 only reinforced their opinion that a reliable method of pilot control was the key to successful – and safe – flight. At the outset of their experiments they regarded control as the unsolved third part of "the flying problem". The other two parts – wings and engines – they believed were already sufficiently promising.

The Wright brothers' plan thus differed sharply from more experienced practitioners of the day, notably Ader, Maxim, and Langley, who all built powerful engines, attached them to airframes equipped with untested control devices, and expected to take to the air with no previous flying experience. Although agreeing with Lilienthal's idea of practice, the Wrights saw that his method of balance and control by shifting his body weight was inadequate. They were determined to find something better.

On the basis of observation, Wilbur concluded that birds changed the angle of the ends of their wings to make their bodies roll right or left. The brothers decided this would also be a good way for a flying machine to turn – to "bank" or "lean" into the turn just like a bird – and just like a person riding a bicycle, an experience with which they were thoroughly familiar. Equally important, they hoped this method would enable recovery when the wind tilted the machine to one side (lateral balance). They puzzled over how to achieve the same effect with man-made wings and eventually discovered wing-warping when Wilbur idly twisted a long inner-tube box at the bicycle shop.

Other aeronautical investigators regarded flight as if it were not so different from surface locomotion, except the surface would be elevated. They thought in terms of a ship's rudder for steering, while the flying machine remained essentially level in the air, as did a train or an automobile or a ship at the surface. The idea of deliberately leaning, or rolling, to one side either seemed undesirable or did not enter their thinking. Some of these other investigators, including Langley and Chanute, sought the elusive ideal of "inherent stability", believing the pilot of a flying machine would not be able to react quickly enough to wind disturbances to use mechanical controls effectively. The Wright brothers, in contrast, wanted the pilot to have absolute control. For that reason, their early designs made no concessions toward built-in stability (such as dihedral wings). They deliberately designed their 1903 first powered flyer with anhedral (drooping) wings, which are inherently unstable, but less susceptible to upset by gusty cross winds.

Flights

Toward flight

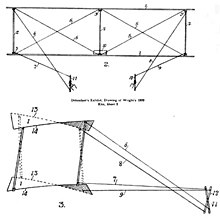

On July 27, 1899, the brothers put wing warping to the test by building and flying a biplane kite with a 5-foot (1.5 m) wingspan, and a curved wing with a 1-foot (0.30 m) chord. When the wings were warped, or twisted, the trailing edge that was warped down produced more lift than the opposite wing, causing a rolling motion. The warping was controlled by four lines between kite and crossed sticks held by the kite flyer. In return, the kite was under lateral control.

In 1900 the brothers went to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, to begin their manned gliding experiments. In his reply to Wilbur's first letter, Octave Chanute had suggested the mid-Atlantic coast for its regular breezes and soft sandy landing surface. Wilbur also requested and examined U.S. Weather Bureau data, and decided on Kitty Hawk after receiving information from the government meteorologist stationed there.

Kitty Hawk, although remote, was closer to Dayton than other places Chanute had suggested, including California and Florida. The spot also gave them privacy from reporters, who had turned the 1896 Chanute experiments at Lake Michigan into something of a circus. Chanute visited them in camp each season from 1901 to 1903 and saw gliding experiments, but not the powered flights.

Gliders

The Wrights based the design of their kite and full-size gliders on work done in the 1890s by other aviation pioneers. They adopted the basic design of the Chanute-Herring biplane hang glider ("double-decker" as the Wrights called it), which flew well in the 1896 experiments near Chicago, and used aeronautical data on lift that Otto Lilienthal had published. The Wrights designed the wings with camber, a curvature of the top surface.

The brothers did not discover this principle, but took advantage of it. The better lift of a cambered surface compared to a flat one was first discussed scientifically by Sir George Cayley. Lilienthal, whose work the Wrights carefully studied, used cambered wings in his gliders, proving in flight the advantage over flat surfaces. The wooden uprights between the wings of the Wright glider were braced by wires in their own version of Chanute's modified Pratt truss, a bridge-building design he used for his biplane glider (initially built as a triplane). The Wrights mounted the horizontal elevator in front of the wings rather than behind, apparently believing this feature would help to avoid, or protect them from, a nosedive and crash like the one that killed Lilienthal. Wilbur incorrectly believed a tail was not necessary, and their first two gliders did not have one.

According to some Wright biographers, Wilbur probably did all the gliding until 1902, perhaps to exercise his authority as older brother and to protect Orville from harm as he did not want to have to explain to their father, Bishop Wright, if Orville got injured.

| Wingspan | Wing area | Chord | Camber | Aspect ratio | Length | Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 17 ft 6 in (5.33 m) | 165 sq ft (15 m) | 5 ft (2 m) | 1/20 | 3.5:1 | 11 ft 6 in (3.51 m) | 52 lb (24 kg) |

| 1901 | 22 ft (7 m) | 290 sq ft (27 m) | 7 ft (2.1 m) | 1/12*,1/19 | 3:1 | 14 ft (4.3 m) | 98 lb (44 kg) |

| 1902 | 32 ft 1 in (9.78 m) | 305 sq ft (28 m) | 5 ft (1.5 m) | 1/20–1/24 | 6.5:1 | 17 ft (5.2 m) | 112 lb (51 kg) |

* (This airfoil caused severe stability problems; the Wrights modified the camber on-site.)

1900

The brothers flew the glider for only a few days in the early autumn of 1900 at Kitty Hawk. In the first tests, probably on October 3, Wilbur was aboard while the glider flew as a kite not far above the ground with men below holding tether ropes. Most of the kite tests were unpiloted, with sandbags or chains and even a local boy as ballast.

They tested wing-warping using control ropes from the ground. The glider was also tested unmanned while suspended from a small homemade tower. Wilbur, but not Orville, made about a dozen free glides on only a single day, October 20. For those tests the brothers trekked four miles (6 km) south to the Kill Devil Hills, a group of sand dunes up to 100 feet (30 m) high (where they made camp in each of the next three years). Although the glider's lift was less than expected, the brothers were encouraged because the craft's front elevator worked well and they had no accidents. However, the small number of free glides meant they were not able to give wing-warping a true test.

The pilot lay flat on the lower wing, as planned, to reduce aerodynamic drag. As a glide ended, the pilot was supposed to lower himself to a vertical position through an opening in the wing and land on his feet with his arms wrapped over the framework. Within a few glides, however, they discovered the pilot could remain prone on the wing, headfirst, without undue danger when landing. They made all their flights in that position for the next five years.

1901

Before returning to Kitty Hawk in the summer of 1901, Wilbur published two articles, "The Angle of Incidence" in The Aeronautical Journal, and "The Horizontal Position During Gliding Flight" in Illustrierte Aeronautische Mitteilungen. The brothers brought all of the material they thought was needed to be self-sufficient at Kitty Hawk. Besides living in tents once again, they built a combination workshop and hangar. Measuring 25 feet (7.6 m) long by 16 feet (4.9 m) wide, the ends opened upward for easy glider access.

Hoping to improve lift, they built the 1901 glider with a much larger wing area and made dozens of flights in July and August for distances of 50 to 400 ft (15 to 122 m). The glider stalled a few times, but the parachute effect of the forward elevator allowed Wilbur to make a safe flat landing, instead of a nose-dive. These incidents wedded the Wrights even more strongly to the canard design, which they did not give up until 1910. The glider, however, delivered two major disappointments. It produced only about one-third the lift calculated and sometimes pointed opposite the intended direction of a turn – a problem later known as adverse yaw – when Wilbur used the wing-warping control. On the trip home a deeply dejected Wilbur remarked to Orville that man would not fly in a thousand years.

The poor lift of the gliders led the Wrights to question the accuracy of Lilienthal's data, as well as the "Smeaton coefficient" of air pressure, a value which had been in use for over 100 years and was part of the accepted equation for lift.

The lift equation Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "http://localhost:6011/en.wikipedia.org/v1/":): {\displaystyle L = k\;S\;V^2\;C_L} L = lift in pounds

k = coefficient of air pressure (Smeaton coefficient)

S = total area of lifting surface in square feet

V = velocity (headwind plus ground speed) in miles per hour

CL = coefficient of lift (varies with wing shape)

The Wrights used this equation to calculate the amount of lift that a wing would produce. Over the years a wide variety of values had been measured for the Smeaton coefficient; Chanute identified up to 50 of them. Wilbur knew that Langley, for example, had used a lower number than the traditional one. Intent on confirming the correct Smeaton value, Wilbur performed his own calculations using measurements collected during kite and free flights of the 1901 glider. His results correctly showed that the coefficient was very close to 0.0033 (similar to the number Langley used), not the traditional 0.0054, which would significantly exaggerate predicted lift.

The brothers decided to find out if Lilienthal's data for lift coefficients were correct. They devised an experimental apparatus which consisted of a freely rotating bicycle wheel mounted horizontally in front of the handlebars of a bicycle. The brothers took turns pedaling the bicycle vigorously, creating air flow over the horizontal wheel. Attached vertically to the wheel were an airfoil and a flat plate mounted 90° away. As air passed by the airfoil, the lift it generated, if unopposed, would cause the wheel to rotate.

The flat plate was oriented so its drag would push the wheel in the opposite direction of the airfoil. The airfoil and flat plate were made in specific sizes such that, according to Lilienthal's measurements, the lift generated by the airfoil would exactly counterbalance the drag generated by the flat plate and the wheel would not turn. However, when the brothers tested the device, the wheel did turn. The experiment confirmed their suspicion that either the standard Smeaton coefficient or Lilienthal's coefficients of lift and drag – or all of them – were in error.

They then built a six-foot (1.8 m) wind tunnel in their shop, and between October and December 1901 conducted systematic tests on dozens of miniature wings. The "balances" they devised and mounted inside the tunnel to hold the wings looked crude, made of bicycle spokes and scrap metal, but were "as critical to the ultimate success of the Wright brothers as were the gliders." The devices allowed the brothers to balance lift against drag and accurately calculate the performance of each wing. They could also see which wings worked well as they looked through the viewing window in the top of the tunnel. The tests yielded a trove of valuable data never before known and showed that the poor lift of the 1900 and 1901 gliders was entirely due to an incorrect Smeaton value, and that Lilienthal's published data were fairly accurate for the tests he had done.

Before the detailed wind tunnel tests, Wilbur traveled to Chicago at Chanute's invitation to give a lecture to the Western Society of Engineers on September 18, 1901. He presented a thorough report about the 1900–1901 glider experiments and complemented his talk with a lantern slide show of photographs. Wilbur's speech was the first public account of the brothers' experiments. A report was published in the Journal of the society, which was then separately published as an offprint titled Some Aeronautical Experiments in a 300 copy printing.

1902

Lilienthal had made "whirling arm" tests on only a few wing shapes, and the Wrights mistakenly assumed the data would apply to their wings, which had a different shape. The Wrights took a huge step forward and made basic wind tunnel tests on 200 scale-model wings of many shapes and airfoil curves, followed by detailed tests on 38 of them. An important discovery was the benefit of longer narrower wings: in aeronautical terms, wings with a larger aspect ratio (wingspan divided by chord – the wing's front-to-back dimension). Such shapes offered much better lift-to-drag ratio than the stubbier wings the brothers had tried so far. With this knowledge, and a more accurate Smeaton number, the Wrights designed their 1902 glider.

The wind tunnel tests, made from October to December 1901, were described by biographer Fred Howard as "the most crucial and fruitful aeronautical experiments ever conducted in so short a time with so few materials and at so little expense". In their September 1908 Century Magazine article, the Wrights explained, "The calculations on which all flying machines had been based were unreliable, and ... every experiment was simply groping in the dark ... We cast it all aside and decided to rely entirely upon our own investigations."

The 1902 glider wing had a flatter airfoil, with the camber reduced to a ratio of 1-in-24, in contrast to the previous thicker wing. The larger aspect ratio was achieved by increasing the wingspan and shortening the chord. The glider also had a new structural feature: A fixed, rear vertical rudder, which the brothers hoped would eliminate turning problems. However, the 1902 glider encountered trouble in crosswinds and steep banked turns, when it sometimes spiraled into the ground – a phenomenon the brothers called "well digging". According to Combs, "They knew that when the earlier 1901 glider banked, it would begin to slide sideways through the air, and if the side motion was left uncorrected, or took place too quickly, the glider would go into an uncontrolled pivoting motion. Now, with vertical fins added to correct this, the glider again went into a pivoting motion, but in the opposite direction, with the nose swinging downward."

Orville apparently visualized that the fixed rudder resisted the effect of corrective wing-warping when attempting to level off from a turn. He wrote in his diary that on the night of October 2, "I studied out a new vertical rudder". The brothers then decided to make the rear rudder movable to solve the problem. They hinged the rudder and connected it to the pilot's warping "cradle", so a single movement by the pilot simultaneously controlled wing-warping and rudder deflection. The apparatus made the trailing edge of the rudder turn away from whichever end of the wings had more drag (and lift) due to warping. The opposing pressure produced by turning the rudder enabled corrective wing-warping to reliably restore level flight after a turn or a wind disturbance. Furthermore, when the glider banked into a turn, rudder pressure overcame the effect of differential drag and pointed the nose of the aircraft in the direction of the turn, eliminating adverse yaw.

In short, the Wrights discovered the true purpose of the movable vertical rudder. Its role was not to change the direction of flight, as a rudder does in sailing, but rather, to aim or align the aircraft correctly during banking turns and when leveling off from turns and wind disturbances. The actual turn – the change in direction – was done with roll control using wing-warping. The principles remained the same when ailerons superseded wing-warping.

With their new method, the Wrights achieved true control in turns for the first time on October 9, a major milestone. From September 20 until the last weeks of October, they flew over a thousand flights. The longest duration was up to 26 seconds, and the longest distance more than 600 feet (180 m). Having demonstrated lift, control, and stability, the brothers now turned their focus to the problem of power.

Thus did three-axis control evolve: wing-warping for roll (lateral motion), forward elevator for pitch (up and down) and rear rudder for yaw (side to side). On March 23, 1903, the Wrights applied for their famous patent for a "Flying Machine", based on their successful 1902 glider. Some aviation historians believe that applying the system of three-axis flight control on the 1902 glider was equal to, or even more significant, than the addition of power to the 1903 Flyer. Peter Jakab of the Smithsonian asserts that perfection of the 1902 glider essentially represents invention of the airplane.

Adding power

In addition to developing the lift equation, the brothers also developed the equation for drag. It is of the same form as the lift equation, except the coefficient of drag replaces the coefficient of lift, computing drag instead of lift. They used this equation to answer the question, "Is there enough power in the engine to produce a thrust adequate to overcome the drag of the total frame ...," in the words of Combs. The Wrights then "... measured the pull in pounds on various parts of their aircraft, including the pull on each of the wings of the biplane in level position in known wind velocities ... They also devised a formula for power-to-weight ratio and propeller efficiency that would answer whether or not they could supply to the propellers the power necessary to deliver the thrust to maintain flight ... they even computed the thrust of their propellers to within 1 percent of the thrust actually delivered ..."

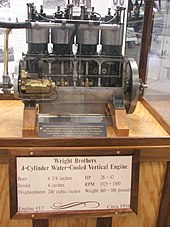

In 1903 the brothers built the powered Wright Flyer, using their preferred material for construction, spruce, a strong and lightweight wood, and Pride of the West muslin for surface coverings. They also designed and carved their own wooden propellers, and had a purpose-built gasoline engine fabricated in their bicycle shop. They thought propeller design would be a simple matter and intended to adapt data from shipbuilding. However, their library research disclosed no established formulae for either marine or air propellers, and they found themselves with no sure starting point. They discussed and argued the question, sometimes heatedly, until they concluded that an aeronautical propeller is essentially a wing rotating in the vertical plane. On that basis, they used data from more wind tunnel tests to design their propellers. The finished blades were just over eight feet long, made of three laminations of glued spruce. The Wrights decided on twin "pusher" propellers (counter-rotating to cancel torque), which would act on a greater quantity of air than a single relatively slow propeller and not disturb airflow over the leading edge of the wings.

Wilbur made a March 1903 entry in his notebook indicating the prototype propeller was 66% efficient. Modern wind tunnel tests on reproduction 1903 propellers show they were more than 75% efficient under the conditions of the first flights, "a remarkable feat", and actually had a peak efficiency of 82%. The Wrights wrote to several engine manufacturers, but none could meet their need for a sufficiently light-weight powerplant. They turned to their shop mechanic, Charlie Taylor, who built an engine in just six weeks in close consultation with the brothers.

To keep the weight down the engine block was cast from aluminum, a rare practice at the time. The Wright/Taylor engine had a primitive version of a carburetor, and had no fuel pump. Gasoline was gravity-fed from the fuel tank mounted on a wing strut into a chamber next to the cylinders where it was mixed with air: The fuel-air mixture was then vaporized by heat from the crankcase, forcing it into the cylinders.

The propeller drive chains, resembling those of bicycles, were supplied by a manufacturer of heavy-duty automobile chains. The Flyer cost less than a thousand dollars, in contrast to more than $50,000 in government funds given to Samuel Langley for his man-carrying Great Aerodrome. In 1903 $1,000 was equivalent to $34,000 in 2023. The Wright Flyer had a wingspan of 40.3 ft (12.3 m), weighed 605 lb (274 kg), and had a 12 horsepower (8.9 kW), 180 lb (82 kg) engine.

On June 24, 1903, Wilbur made a second presentation in Chicago to the Western Society of Engineers. He gave details about their 1902 experiments and glider flights, but avoided any mention of their plans for powered flight.

First powered flight

In camp at Kill Devil Hills, the Wrights endured weeks of delays caused by broken propeller shafts during engine tests. After the shafts were replaced (requiring two trips back to Dayton), Wilbur won a coin toss and made a three-second flight attempt on December 14, 1903, stalling after takeoff and causing minor damage to the Flyer. Because December 13, 1903, was a Sunday, the brothers did not make any attempts that day, even though the weather was good, so their first powered test flight happened on the 121st anniversary of the first hot air balloon test flight that the Montgolfier brothers had made on December 14, 1782. In a message to their family, Wilbur referred to the trial as having "only partial success", stating "the power is ample, and but for a trifling error due to lack of experience with this machine and this method of starting, the machine would undoubtedly have flown beautifully."

Following repairs, the Wrights finally took to the air on December 17, 1903, making two flights each from level ground into a freezing headwind gusting to 27 miles per hour (43 km/h). The first flight, by Orville at 10:35 am, of 120 feet (37 m) in 12 seconds, at a speed of only 6.8 miles per hour (10.9 km/h) over the ground, was recorded in a famous photograph. The next two flights covered approximately 175 and 200 feet (53 and 61 m), by Wilbur and Orville respectively. Their altitude was about 10 feet (3.0 m) above the ground. The following is Orville Wright's account of the final flight of the day:

Wilbur started the fourth and last flight at just about 12 o'clock. The first few hundred feet were up and down, as before, but by the time three hundred ft had been covered, the machine was under much better control. The course for the next four or five hundred feet had but little undulation. However, when out about eight hundred feet the machine began pitching again, and, in one of its darts downward, struck the ground. The distance over the ground was measured to be 852 feet; the time of the flight was 59 seconds. The frame supporting the front rudder was badly broken, but the main part of the machine was not injured at all. We estimated that the machine could be put in condition for flight again in about a day or two.

Five people witnessed the flights: Adam Etheridge, John T. Daniels (who snapped the famous "first flight" photo using Orville's pre-positioned camera), and Will Dough, all of the U.S. government coastal lifesaving crew; area businessman W.C. Brinkley; and Johnny Moore, a teenaged boy who lived in the area. After the men hauled the Flyer back from its fourth flight, a powerful gust of wind flipped it over several times, despite the crew's attempt to hold it down. Severely damaged, the Wright Flyer never flew again. The brothers shipped the airplane home, and years later Orville restored it, lending it to several U.S. locations for display, then to the Science Museum in London (see Smithsonian dispute below), before it was finally installed in 1948 in the Smithsonian Institution, its current residence.

The Wrights sent a telegram about the flights to their father, requesting that he "inform press". However, the Dayton Journal refused to publish the story, saying the flights were too short to be important. Meanwhile, against the brothers' wishes, a telegraph operator leaked their message to a Virginia newspaper, which concocted a highly inaccurate news article that was reprinted the next day in several newspapers elsewhere, including Dayton.

The Wrights issued their own factual statement to the press in January. Nevertheless, the flights did not create public excitement – if people even knew about them – and the news soon faded. In Paris, however, Aero Club of France members, already stimulated by Chanute's reports of Wright gliding successes, took the news more seriously and increased their efforts to catch up to the brothers.

An analysis in 1985 by Professor Fred E.C. Culick and Henry R. Jex demonstrated that the 1903 Wright Flyer was so unstable as to be almost unmanageable by anyone but the Wrights, who had trained themselves in the 1902 glider. In a recreation attempt on the event's 100th anniversary on December 17, 2003, Kevin Kochersberger, piloting an exact replica, failed in his effort to match the success that the Wright brothers had achieved with their piloting skill.

Establishing legitimacy

In 1904 the Wrights built the Wright Flyer II. They decided to avoid the expense of travel and bringing supplies to the Outer Banks and set up an airfield at Huffman Prairie, a cow pasture eight miles (13 km) northeast of Dayton. The Wrights referred to the airfield as Simms Station in their flying school brochure. They received permission to use the field rent-free from owner and bank president Torrance Huffman.

They invited reporters to their first flight attempt of the year on May 23, on the condition that no photographs be taken. Engine troubles and slack winds prevented any flying, and they could manage only a very short hop a few days later with fewer reporters present. Library of Congress historian Fred Howard noted some speculation that the brothers had intentionally failed to fly in order to cause reporters to lose interest in their experiments. Whether that is true is not known, but after their poor showing local newspapers virtually ignored them for the next year and a half.

The Wrights were glad to be free from the distraction of reporters. The absence of newsmen also reduced the chance of competitors learning their methods. After the Kitty Hawk powered flights, the Wrights made a decision to begin withdrawing from the bicycle business so they could concentrate on creating and marketing a practical airplane. This was financially risky, since they were neither wealthy nor government-funded (unlike other experimenters such as Ader, Maxim, Langley, and Santos-Dumont). The Wright brothers did not have the luxury of being able to give away their invention: It had to be their livelihood. Thus, their secrecy intensified, encouraged by advice from their patent attorney, Henry Toulmin, not to reveal details of their machine.

At Huffman Prairie, lighter winds made takeoffs harder, and they had to use a longer starting rail than the 60-foot (18 m) rail used at Kitty Hawk. The first flights in 1904 revealed problems with longitudinal stability, solved by adding ballast and lengthening the supports for the elevator. During the spring and summer they suffered many hard landings, often damaging the aircraft and causing minor injuries. On August 13, making an unassisted takeoff, Wilbur finally exceeded their best Kitty Hawk effort with a flight of 1,300 feet (400 m). They then decided to use a weight-powered catapult to make takeoffs easier and tried it for the first time on September 7.

On September 20, 1904, Wilbur flew the first complete circle in history by a manned heavier-than-air powered machine, covering 4,080 feet (1,244 m) in about a minute and a half. Their two best flights were November 9 by Wilbur and December 1 by Orville, each exceeding five minutes and covering nearly three miles in almost four circles. By the end of the year the brothers had accumulated about 50 minutes in the air in 105 flights over the rather soggy 85 acres (34 ha) pasture, which, remarkably, is virtually unchanged today from its original condition and is now part of Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park, adjacent to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

The Wrights scrapped the battered and much-repaired aircraft, but saved the engine, and in 1905 built a new airplane, the Flyer III. Nevertheless, at first this Flyer offered the same marginal performance as the first two. Its maiden flight was on June 23 and the first few flights were no longer than 10 seconds. After Orville suffered a bone-jarring and potentially fatal crash on July 14, they rebuilt the Flyer with the forward elevator and rear rudder both enlarged and placed several feet farther away from the wings. They also installed a separate control for the rear rudder instead of linking it to the wing-warping "cradle" as before.

Each of the three axes – pitch, roll, and yaw – now had its own independent control. These modifications greatly improved stability and control, enabling a series of six dramatic "long flights" ranging from 17 to 38 minutes and 11 to 24 miles (18 to 39 km) around the three-quarter mile course over Huffman Prairie between September 26 and October 5. Wilbur made the last and longest flight, 24.5 miles (39.4 km) in 38 minutes and 3 seconds, ending with a safe landing when the fuel ran out. The flight was seen by several invited friends, their father Milton, and neighboring farmers.

Reporters showed up the next day (only their second appearance at the field since May the previous year), but the brothers declined to fly. The long flights convinced the Wrights they had achieved their goal of creating a flying machine of "practical utility" which they could offer to sell.

The only photos of the flights of 1904–1905 were taken by the brothers. (A few photos were damaged in the Great Dayton Flood of 1913, but most survived intact.) In 1904 Ohio beekeeping businessman Amos Root, a technology enthusiast, saw a few flights including the first circle. Articles he wrote for his beekeeping magazine were the only published eyewitness reports of the Huffman Prairie flights, except for the unimpressive early hop local newsmen saw. Root offered a report to Scientific American magazine, but the editor turned it down. As a result, the news was not widely known outside Ohio, and was often met with skepticism. The Paris edition of the Herald Tribune headlined a 1906 article on the Wrights "Flyers or liars?".

In years to come, Dayton newspapers would proudly celebrate the hometown Wright brothers as national heroes, but the local reporters somehow missed one of the most important stories in history as it was happening a few miles from their doorstep. J.M. Cox, who published the Dayton Daily News at that time, expressed the attitude of newspapermen – and the public – in those days when he admitted years later: "Frankly, none of us believed it."

A few newspapers published articles about the long flights, but no reporters or photographers had been there. The lack of splashy eyewitness press coverage was a major reason for disbelief in Washington, DC, and Europe, and in journals like Scientific American, whose editors doubted the "alleged experiments" and asked how U.S. newspapers, "alert as they are, allowed these sensational performances to escape their notice."

In October 1904, the brothers were visited by the first of many important Europeans they would befriend in coming years, Colonel J.E. Capper, later superintendent of the Royal Balloon Factory. Capper and his wife were visiting the United States to investigate the aeronautical exhibits at the St. Louis World Fair, but had been given a letter of introduction to both Chanute and the Wrights by Patrick Alexander. Capper was very favorably impressed by the Wrights, who showed him photographs of their aircraft in flight.

The Wright brothers were certainly complicit in the lack of attention they received. Fearful of competitors stealing their ideas, and still without a patent, they flew on only one more day after October 5. From then on, they refused to fly anywhere unless they had a firm contract to sell their aircraft. They wrote to the U.S. government, then to Britain, France and Germany with an offer to sell a flying machine, but were rebuffed because they insisted on a signed contract before giving a demonstration. They were unwilling even to show their photographs of the airborne Flyer.

The American military, having recently spent $50,000 on the Langley Aerodrome – a product of the nation's foremost scientist – only to see it plunge twice into the Potomac River "like a handful of mortar", was particularly unreceptive to the claims of two unknown bicycle makers from Ohio. Thus, doubted or scorned, the Wright brothers continued their work in semi-obscurity, while other aviation pioneers like Santos-Dumont, Henri Farman, Léon Delagrange, and American Glenn Curtiss entered the limelight.

European skepticism

In 1906, skeptics in the European aviation community had converted the press to an anti-Wright brothers stance. European newspapers, especially those in France, were openly derisive, calling them bluffeurs (bluffers). Ernest Archdeacon, founder of the Aéro-Club de France, was publicly scornful of the brothers' claims despite published reports; specifically, he wrote several articles and, in 1906, stated that "the French would make the first public demonstration of powered flight." The Paris edition of the New York Herald summed up Europe's opinion of the Wright brothers in an editorial on February 10, 1906: "The Wrights have flown or they have not flown. They possess a machine or they do not possess one. They are in fact either fliers or liars. It is difficult to fly. It's easy to say, 'We have flown'."

In 1908, after the Wrights' first flights in France, Archdeacon publicly admitted he had done them an injustice.

Contracts and return to Kitty Hawk

The brothers contacted the United States Department of War, the British War Office and a French syndicate on October 19, 1905. The U.S. Board of Ordnance and Fortification replied on October 24, 1905, specifying they would take no further action "until a machine is produced which by actual operation is shown to be able to produce horizontal flight and to carry an operator." In May 1908, Orville wrote:

A practical flyer having been finally realized, we spent the years 1906 and 1907 in constructing new machines and in business negotiations. It was not till May of this year that experiments were resumed at Kill Devil Hill, North Carolina ..."

The brothers turned their attention to Europe, especially France, where enthusiasm for aviation ran high, and journeyed there for the first time in 1907 for face-to-face talks with government officials and businessmen. They also met with aviation representatives in Germany and Britain. Before traveling, Orville shipped a newly built Model A Flyer to France in anticipation of demonstration flights. In France, Wilbur met Frank P. Lahm, a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Aeronautical Division. Writing to his superiors, Lahm smoothed the way for Wilbur to give an in-person presentation to the U.S. Board of Ordnance and Fortification in Washington, DC, when he returned to the U.S. This time, the Board was favorably impressed, in contrast to its previous indifference.

With further input from the Wrights, the U.S. Army Signal Corps issued Specification 486 in December 1907, inviting bids for construction of a flying machine under military contract. The Wrights submitted their bid in January, and were awarded a contract on February 8, 1908. Then on March 23, 1908, the brothers had a contract to form the French company La Compagnie Générale de Navigation Aérienne. This French syndicate included Lazare Weiller, Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe, Hart O. Berg, and Charles Ranlett Flint.

In May they went back to Kitty Hawk with their 1905 Flyer to practice for their contracted demonstration flights. Their privacy was lost when several correspondents arrived on the scene. The brothers' contracts required them to fly with a passenger, so they modified the 1905 Flyer by installing two upright seats with dual control levers. Charlie Furnas, a mechanic from Dayton, became the first fixed-wing aircraft passenger on separate flights with both brothers on May 14, 1908. Later, Wilbur over-controlled the front elevator and crashed into the sand at about 50 miles per hour (80 km/h). He emerged with bruises and hurt ribs, but the accident ended the practice flights.

Return to glider flights

In October 1911, Orville Wright returned to the Outer Banks again, to conduct safety and stabilization tests with a new glider. On October 24, he soared for 9 minutes and 45 seconds, a record that held for almost 10 years, when gliding as a sport began in the 1920s.

Public showing

The brothers' contracts with the U.S. Army and a French syndicate depended on successful public flight demonstrations that met certain conditions. The brothers had to divide their efforts. Wilbur sailed for Europe; Orville would fly near Washington, DC.

Facing much skepticism in the French aeronautical community and outright scorn by some newspapers that called him a "bluffeur", Wilbur began official public demonstrations on August 8, 1908, at the Hunaudières horse racing track near the town of Le Mans, France. His first flight lasted only 1 minute 45 seconds, but his ability to effortlessly make banking turns and fly a circle amazed and stunned onlookers, including several pioneer French aviators, among them Louis Blériot. In the following days, Wilbur made a series of technically challenging flights, including figure-eights, demonstrating his skills as a pilot and the capability of his flying machine, which far surpassed those of all other pioneering aircraft and pilots of the day.

The French public was thrilled by Wilbur's feats and flocked to the field by the thousands, and the Wright brothers instantly became world-famous. Former doubters issued apologies and effusive praise. L'Aérophile editor Georges Besançon wrote that the flights "have completely dissipated all doubts. Not one of the former detractors of the Wrights dare question, today, the previous experiments of the men who were truly the first to fly ..." Leading French aviation promoter Ernest Archdeacon wrote, "For a long time, the Wright brothers have been accused in Europe of bluff ... They are today hallowed in France, and I feel an intense pleasure ... to make amends."

On October 7, 1908, Edith Berg, the wife of the brothers' European business agent, became the first American woman passenger when she flew with Wilbur – one of many passengers who rode with him that autumn, including Griffith Brewer and Charles Rolls. Wilbur also became acquainted with Léon Bollée and his family. Bollée was the owner of an automobile factory where Wilbur would assemble the Flyer and where he would be provided with hired assistance. Bollée and his wife would fly that autumn with Wilbur. Madame Carlotta Bollée had been in the latter stages of pregnancy when Wilbur arrived in Le Mans in June 1908 to assemble the Flyer. She was fluent in Greek, French and English and translated the technical discussions between Wright and her husband. Wilbur promised her that he would make his first European flight the day her baby was born which he did, August 8, 1908. He became Elizabeth Bollée's godfather.

Orville followed his brother's success by demonstrating another nearly identical Flyer to the United States Army at Fort Myer, Virginia, starting on September 3, 1908. On September 9, he made the first hour-long flight, lasting 62 minutes and 15 seconds. On the same day he took up Frank P. Lahm as a passenger, and then Major George Squier three days later.

On September 17, Army lieutenant Thomas Selfridge rode along as his passenger, serving as an official observer. A few minutes into the flight at an altitude of about 100 feet (30 m), a propeller split and shattered, sending the Flyer out of control. Selfridge suffered a fractured skull in the crash and died that evening in the nearby Army hospital, becoming the first airplane crash fatality. Orville was badly injured, suffering a broken left leg and four broken ribs. Twelve years later, after he suffered increasingly severe pains, X-rays revealed the accident had also caused three hip bone fractures and a dislocated hip.

The brothers' sister Katharine, a school teacher, rushed from Dayton to Virginia and stayed by Orville's side for the seven weeks of his hospitalization. She helped negotiate a one-year extension of the Army contract. A friend visiting Orville in the hospital asked, "Has it got your nerve?" "Nerve?" repeated Orville, slightly puzzled. "Oh, do you mean will I be afraid to fly again? The only thing I'm afraid of is that I can't get well soon enough to finish those tests next year."

Deeply shocked and upset by the accident, Wilbur determined to make even more impressive flight demonstrations; in the ensuing days and weeks he set new records for altitude and duration. On September 28, Wilbur won the Commission of Aviation prize, and then on December 31, the Coupe Michelin. In January 1909 Orville and Katharine joined him in France, and for a time they were the three most famous people in the world, sought after by royalty, the rich, reporters, and the public. The kings of Great Britain, Spain, and Italy came to see Wilbur fly.

All three Wrights relocated to Pau, where Wilbur made many more public flights in nearby Pont Long. Wilbur gave rides to a procession of officers, journalists, and statesmen, including his sister Katharine on March 17, 1909. The brothers established the world's first flying school to meet the French syndicate requirements to train three French pilots (Charles de Lambert, Paul Tissandier, and Paul-Nicolas Lucas-Girardville). In April the Wrights went to Rome where Wilbur assembled another Flyer. At Centocelle, Wilbur made demonstrations flights, and trained three Italian military pilots (Mario Calderara, Umbert Savoia, and Guido Castagneris). A Universal cameraman flew as a passenger, and filmed the first motion pictures from an airplane.

After their return to the U.S. on May 13, 1909, the brothers and Katharine were invited to the White House where on June 10, President Taft bestowed awards upon them. Dayton followed up with a lavish two-day homecoming celebration on June 17 and 18. On July 27, 1909 Orville, with Wilbur assisting on the ground, completed the proving flights for the U.S. Army. The flights met the requirements that the aircraft carry two persons while remaining aloft for an hour and achieve an average speed of at least 40 miles per hour (64 km/h).

President Taft, his cabinet, and members of Congress were part of the viewing crowd of 10,000. Following the successful flights, the Army awarded the Wrights $25,000, plus $2500 for each mile per hour they exceeded 40 miles per hour. Orville and Katharine then traveled to Germany, where Orville made demonstration flights at Tempelhof in September 1909, including a flight with the Crown Prince of Germany as a passenger.

On October 4, 1909, Wilbur made a flight seen by about a million people in Manhattan during the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York City. He took off from Governors Island, flew north over the Hudson River to Grant's Tomb and returned to Governors Island. The aircraft was equipped with an unusual accessory for the flight: a canoe attached to the underside framework as a flotation device in case of a ditching. On October 8 in College Park, Maryland, Wilbur began pilot training for Army officers Frank P. Lahm and Frederick E. Humphreys, joined later that month by Benjamin Foulois.

Family flights

On May 25, 1910, back at Huffman Prairie, Orville piloted two unique flights. First, he took off on a six-minute flight with Wilbur as his passenger, the only time the Wright brothers ever flew together. They received permission from their father to make the flight. They had always promised Milton they would never fly together to avoid the chance of a double tragedy and to ensure one brother would remain to continue their experiments. Next, Orville took his 82-year-old father on a nearly 7-minute flight, the only powered aerial excursion of Milton Wright's life. The aircraft rose to about 350 feet (107 m) while the elderly Wright called to his son, "Higher, Orville, higher!".

Patent war

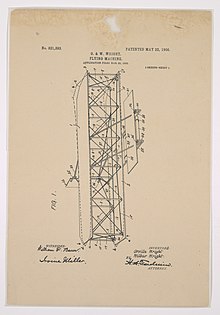

The Wright brothers wrote their 1903 patent application themselves, but it was rejected. In January 1904, they hired Ohio patent attorney Henry Toulmin, and on May 22, 1906, they were granted U.S. Patent 821393 for "new and useful Improvements in Flying Machines".

The patent illustrates a non-powered flying machine – namely, the 1902 glider. The patent's importance lies in its claim of a new and useful method of controlling a flying machine, powered or not. The technique of wing-warping is described, but the patent explicitly states that other methods instead of wing-warping could be used for adjusting the outer portions of a machine's wings to different angles on the right and left sides to achieve lateral (roll) control.

The concept of varying the angle presented to the air near the wingtips, by any suitable method, is central to the patent. The patent also describes the steerable rear vertical rudder and its innovative use in combination with wing-warping, enabling the airplane to make a coordinated turn, a technique that prevents hazardous adverse yaw, the problem Wilbur had when trying to turn the 1901 glider. Finally, the patent describes the forward elevator, used for ascending and descending.

In March 1904, the Wright Brothers applied for French and German patents. The French patent was granted on July 1, 1904. According to Combs, regarding the U.S. patent, "... by 1906 the drawings in the Wright patents were available to anyone who wanted badly enough to get them. And they gave proof – in vivid, technical detail – of how to get into the air."

Lawsuits begin

Glenn Curtiss and other early aviators devised ailerons to emulate lateral control described in the patent and demonstrated by the Wrights in their public flights. Soon after the historic July 4, 1908, one-kilometer flight by Curtiss in the AEA June Bug, the Wrights warned him not to infringe their patent by profiting from flying or selling aircraft that used ailerons.

Orville wrote Curtiss, "Claim 14 of our patent no. 821,393, specifically covers the combination which we are informed you are using. If it is your desire to enter the exhibition business, we would be glad to take up the matter of a license to operate under our patent for that purpose."

Curtiss was at the time a member of the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), headed by Alexander Graham Bell, where in 1908 he had helped reinvent wingtip ailerons for their Aerodrome No. 2, known as the AEA White Wing

Curtiss refused to pay license fees to the Wrights and sold an airplane equipped with ailerons to the Aeronautic Society of New York in 1909. The Wrights filed a lawsuit, beginning a years-long legal conflict. They also sued foreign aviators who flew at U.S. exhibitions, including the leading French aviator Louis Paulhan. The Curtiss people derisively suggested that if someone jumped in the air and waved his arms, the Wrights would sue.

European companies which bought foreign patents the Wrights had received sued other manufacturers in their countries. Those lawsuits were only partly successful. Despite a pro-Wright ruling in France, legal maneuvering dragged on until the patent expired in 1917. A German court ruled the patent invalid because of prior disclosure in speeches by Wilbur Wright in 1901, and Chanute in 1903. In the U.S. the Wrights made an agreement with the Aero Club of America to license airshows which the Club approved, freeing participating pilots from a legal threat. Promoters of approved shows paid fees to the Wrights. The Wright brothers won their initial case against Curtiss in February 1913 when a judge ruled that ailerons were covered under the patent. The Curtiss company appealed the decision.

From 1910 until his death from typhoid fever in 1912, Wilbur took the leading role in the patent struggle, travelling incessantly to consult with lawyers and testify in what he felt was a moral cause, particularly against Curtiss, who was creating a large company to manufacture aircraft. The Wrights' preoccupation with the legal issue stifled their work on new designs, and by 1911 Wright airplanes were considered inferior to those of European makers. Indeed, aviation development in the U.S. was suppressed to such an extent that, when the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917, no acceptable American-designed airplanes were available, and American forces were compelled to use French machines. Orville and Katharine Wright believed Curtiss was partly responsible for Wilbur's premature death, which occurred in the wake of his exhausting travels and the stress of the legal battle.

Victory and cooperation

In January 1914, a U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the verdict against the Curtiss company, which continued to avoid penalties through legal tactics. Orville apparently felt vindicated by the decision, and much to the frustration of company executives, he did not push vigorously for further legal action to ensure a manufacturing monopoly. In fact, he was planning to sell the company and departed in 1915. In 1917, with World War I underway, the U.S. government pressured the industry to form a cross-licensing organization, the Manufacturers Aircraft Association, to which member companies paid a blanket fee for the use of aviation patents, including the original and subsequent Wright patents. The "patent war" ended, although side issues lingered in the courts until the 1920s. The Wright Aeronautical Corporation (successor to the Wright-Martin Company), and the Curtiss Aeroplane company, merged in 1929 to form the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, which remains in business today producing high-tech components for the aerospace industry.

Aviation historian C.H. Gibbs-Smith stated a number of times that the Wrights' legal victory would have been "doubtful" if an 1868 patent of "a prior but lost invention" by M.P.W. Boulton of the U.K. had been known in the period 1903–1906. The patent, titled Aërial Locomotion &c, described several engine improvements and conceptual designs and included a technical description and drawings of an aileron control system and an optional feature intended to function as an autopilot. In fact, this patent was well known to participants in the Wright-Curtiss lawsuit. A U.S. federal judge who reviewed previous inventions and patents and upheld the Wright patent against the Curtiss company reached the opposite conclusion of Gibbs-Smith, saying the Boulton patent "is not anticipatory".

Public reactions

The lawsuits damaged the public image of the Wright brothers, who were generally regarded before this as heroes. Critics said the brothers were greedy and unfair, and compared their actions unfavorably to European inventors, who worked more openly. Supporters said the brothers were protecting their interests and were justified in expecting fair compensation for the years of work leading to their successful invention. Their 10-year friendship with Octave Chanute, already strained by tension over how much credit, if any, he might deserve for their success, collapsed after he publicly criticized their actions.

In business

The Wright Company was incorporated on November 22, 1909. The brothers sold their patents to the company for $100,000 and also received one-third of the shares in a million dollar stock issue and a 10 percent royalty on every airplane sold. With Wilbur as president and Orville as vice president, the company set up a factory in Dayton and a flying school / test flight field at Huffman Prairie; the headquarters office was in New York City.

In mid-1910, the Wrights changed the design of the Wright Flyer, moving the horizontal elevator from the front to the back and adding wheels although keeping the skids as part of the undercarriage unit. It had become apparent by then that a rear elevator would make an airplane easier to control, especially as higher speeds grew more common. The new version was designated the "Model B", although the original canard design was never referred to as the "Model A" by the Wrights. However, the U.S. Army Signal Corps which bought the airplane did call it "Wright type A".

There were not many customers for airplanes, so in the spring of 1910 the Wrights hired and trained a team of salaried exhibition pilots to show off their machines and win prize money for the company – despite Wilbur's disdain for what he called "the mountebank business". The team debuted at the Indianapolis Speedway on June 13. Before the year was over, pilots Ralph Johnstone and Arch Hoxsey died in air show crashes, and in November 1911 the brothers disbanded the team on which nine men had served (four other former team members died in crashes afterward).

The Wright Company transported the first known commercial air cargo on November 7, 1910, by flying two bolts of dress silk 65 miles (105 km) from Dayton to Columbus, Ohio, for the Morehouse-Martens Department Store, which paid a $5,000 fee. Company pilot Phil Parmelee made the flight – which was more an exercise in advertising than a simple delivery – in an hour and six minutes with the cargo strapped in the passenger's seat. The silk was cut into small pieces and sold as souvenirs.

In 1910 the Wrights advertised for a person to undertake "plane sewing", which was corrected by the Dayton newspaper that published it to "plain sewing". Ida Holdgreve, a dress maker, applied for the role and became head seamstress at the Wright Company Factory, sewing the fabric "for the wings, stabilizers, rudders, fins and I don't know what all" of the planes produced there. She was trained in how to cut and sew the fabric to stretch it tight over the frame so it wouldn't rip by Duval La Chapelle, who was Wilbur's mechanic in France.

Between 1910 and 1916 the Wright Brothers Flying School at Huffman Prairie trained 115 pilots who were instructed by Orville and his assistants. Several trainees became famous, including Henry "Hap" Arnold, who rose to Five-Star General, commanded U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, and became the first head of the U.S. Air Force; Calbraith Perry Rodgers, who made the first coast-to-coast flight in 1911 (with many stops and crashes) in a Wright Model EX named the "Vin Fiz" (after the sponsor's grape soft drink); and Eddie Stinson, founder of the Stinson Aircraft Company.

Army accidents

In 1912–1913 a series of fatal crashes of Wright airplanes bought by the U.S. Army called into question their safety and design. The death toll reached 11 by 1913, half of them in the Wright model C. All six model C Army airplanes crashed. They had a tendency to nose dive, but Orville insisted that stalls were caused by pilot error. He cooperated with the Army to equip the airplanes with a rudimentary flight indicator to help the pilot avoid climbing too steeply. A government investigation said the Wright model C was "dynamically unsuited for flying", and the American military ended its use of airplanes with "pusher" type propellers, including models made by both the Wright and Curtiss companies, in which the engine was located behind the pilot and likely to crush him in a crash. Orville resisted the switch to manufacturing "tractor-type" propeller aircraft, worried that a design change could threaten the Wright patent infringement case against Curtiss.

Smithsonian feud

S.P. Langley, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution from 1887 until his death in 1906, experimented for years with model flying machines and successfully flew unmanned powered fixed-wing model aircraft in 1896 and 1903. Two tests of his manned full-size motor-driven Aerodrome in October and December 1903, however, were complete failures. Nevertheless, the Smithsonian later proudly displayed the Aerodrome in its museum as the first heavier-than-air craft "capable" of manned powered flight, relegating the Wright brothers' invention to secondary status and triggering a decades-long feud with Orville Wright, whose brother had received help from the Smithsonian when beginning his own quest for flight.

The Smithsonian based its claim for the Aerodrome on short test flights Glenn Curtiss and his team made with it in 1914. The Smithsonian had allowed Curtiss to make major modifications to the craft before attempting to fly it.

The Smithsonian hoped to salvage Langley's aeronautical reputation by proving the Aerodrome could fly; Curtiss wanted to prove the same thing to defeat the Wrights' patent lawsuits against him. The tests had no effect on the patent battle, but the Smithsonian made the most of them, honoring the Aerodrome in its museum and publications. The Institution did not reveal the extensive Curtiss modifications, but Orville Wright learned of them from his brother Lorin and a close friend of his and Wilbur's, Griffith Brewer, who both witnessed and photographed some of the tests.

Orville repeatedly objected to misrepresentation of the Aerodrome, but the Smithsonian was unyielding. Orville responded by lending the restored 1903 Kitty Hawk Flyer to the London Science Museum in 1928, refusing to donate it to the Smithsonian while the Institution "perverted" the history of the flying machine. Orville would never see his invention again, as he died before its return to the United States.

Charles Lindbergh attempted to mediate the dispute, to no avail. In 1942, after years of bad publicity, and encouraged by Wright biographer F.C. Kelly, the Smithsonian finally relented by publishing, for the first time, a list of the Aerodrome modifications and recanting the misleading statements it had published about the 1914 tests. Orville then privately requested the British museum to return the Flyer, but the airplane remained in protective storage for the duration of World War II; it finally came home after Orville's death.

On November 23, 1948, the executors of Orville's estate signed an agreement for the Smithsonian to purchase the Flyer for one dollar. At the insistence of the executors, the agreement also included strict conditions for display of the airplane.

The agreement reads, in part:

Neither the Smithsonian Institution or its successors, nor any museum or other agency, bureau or facilities administered for the United States of America by the Smithsonian Institution or its successors shall publish or permit to be displayed a statement or label in connection with or in respect of any aircraft model or design of earlier date than the 1903 Wright Aeroplane, claiming in effect that such aircraft was capable of carrying a man under its own power in controlled flight.

If this agreement is not fulfilled, the Flyer can be reclaimed by the heir of the Wright brothers. Some aviation enthusiasts, particularly those who promote the legacy of Gustave Whitehead, have accused the Smithsonian of refusing to investigate claims of earlier flights. After a ceremony in the Smithsonian museum, the Flyer went on public display on December 17, 1948, the 45th anniversary of the only day it was flown successfully. The Wright brothers' nephew Milton (Lorin's son), who had seen gliders and the Flyer under construction in the bicycle shop when he was a boy, gave a brief speech and formally transferred the airplane to the Smithsonian, which displayed it with the accompanying label:

The original Wright brothers aeroplane The world's first power-driven heavier-than-air machine in which man made free, controlled, and sustained flight

Invented and built by Wilbur and Orville Wright

Flown by them at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina December 17, 1903

By original scientific research the Wright brothers discovered the principles of human flight

As inventors, builders, and flyers they further developed the aeroplane, taught man to fly, and opened the era of aviation

Later years

Wilbur

Both Wilbur and Orville were lifelong bachelors. Wilbur once quipped that he "did not have time for both a wife and an airplane". The 1909 short silent film Wilbur Wright und seine Flugmaschine (which translates to Wilbur Wright and his Flying Machine) is considered to be the first use of motion picture aerial photography as filmed from a heavier-than-air aircraft. Following a brief training flight he gave to a German pilot in Berlin in June 1911, Wilbur never flew again. He gradually became occupied with business matters for the Wright Company and dealing with different lawsuits. Upon dealing with the patent lawsuits, which had put great strain on both brothers, Wilbur had written in a letter to a French friend:

When we think what we might have accomplished if we had been able to devote this time to experiments, we feel very sad, but it is always easier to deal with things than with men, and no one can direct his life entirely as he would choose.

Wilbur spent the next year before his death traveling, where he spent a full six months in Europe attending to various business and legal matters. Wilbur urged American cities to emulate the European – particularly Parisian – philosophy of apportioning generous public space near every important public building. He was also constantly back and forth between New York, Washington, and Dayton. All of the stresses were taking a toll on Wilbur physically. Orville would remark that he would "come home white".

It was decided by the family that a new and far grander house would be built, using the money that the Wrights had earned through their inventions and business. Called affectionately Hawthorn Hill, building had begun in the Dayton suburb of Oakwood, Ohio, while Wilbur was in Europe. Katharine and Orville oversaw the project in his absence. Wilbur's one known expression upon the design of the house was that he have a room and bathroom of his own. The brothers hired Schenck and Williams, an architectural firm, to design the house, along with input from both Wilbur and Orville. Wilbur did not live to see its completion in 1914.

He became ill on a business trip to Boston in April 1912. The illness is sometimes attributed to eating bad shellfish at a banquet. After returning to Dayton in early May 1912, worn down in mind and body, he fell ill again and was diagnosed with typhoid fever. He lingered on, his symptoms relapsing and remitting for many days. Wilbur died, at age 45, at the Wright family home on May 30. His father wrote about Wilbur in his diary: "A short life, full of consequences. An unfailing intellect, imperturbable temper, great self-reliance and as great modesty, seeing the right clearly, pursuing it steadfastly, he lived and died."

Orville

Orville succeeded to the presidency of the Wright Company upon Wilbur's death. He won the prestigious Collier Trophy in 1914 for development of his automatic stabilizer on the brothers' Wright Model E. Sharing Wilbur's distaste for business but not his brother's executive skills, Orville sold the company in 1915. The Wright Company then became part of Wright-Martin in 1916.

After 42 years living at their residence on 7 Hawthorn Street, Orville, Katharine, and their father, Milton, moved to Hawthorn Hill in spring 1914. Milton died in his sleep on April 3, 1917, at age 88. Up until his death, Milton had been very active, preoccupied with reading, writing articles for religious publications and enjoying his morning walks. He had also marched in a Dayton Woman's Suffrage Parade, along with Orville and Katharine.

Orville made his last flight as a pilot in 1918 in a 1911 Model B. He retired from business and became an elder statesman of aviation, serving on various official boards and committees, including the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), and Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce (ACCA).

Katharine married Henry Haskell of Kansas City, a former Oberlin classmate, in 1926. Orville was furious and inconsolable, feeling he had been betrayed by his sister Katharine. He refused to attend the wedding or even communicate with her. He finally agreed to see her, apparently at Lorin's insistence, just before she died of pneumonia on March 3, 1929.

Orville Wright served in the NACA for 28 years. In 1930, he received the first Daniel Guggenheim Medal established in 1928 by the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics. In 1936, he was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences. In 1939, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued a presidential proclamation which designated the anniversary of Orville's birthday as National Aviation Day, a national observation that celebrates the development of aviation.

On April 19, 1944, the second production Lockheed Constellation, piloted by Howard Hughes and TWA president Jack Frye, flew from Burbank, California, to Washington, D.C., in 6 hours and 57 minutes (2,300 mi, 330.9 mph). On the return trip, the airliner stopped at Wright Field to give Orville Wright his last airplane flight, more than 40 years after his historic first flight. He may even have briefly handled the controls. He commented that the wingspan of the Constellation was longer than the distance of his first flight.

Orville's last major project was supervising the reclamation and preservation of the 1905 Wright Flyer III, which historians describe as the first practical airplane.

Orville expressed sadness in an interview years later about the death and destruction brought about by the bombers of World War II:

We dared to hope we had invented something that would bring lasting peace to the earth. But we were wrong ... No, I don't have any regrets about my part in the invention of the airplane, though no one could deplore more than I do the destruction it has caused. I feel about the airplane much the same as I do in regard to fire. That is, I regret all the terrible damage caused by fire, but I think it is good for the human race that someone discovered how to start fires and that we have learned how to put fire to thousands of important uses.

Orville died at age 76 on January 30, 1948, over 35 years after his brother, following his second heart attack, having lived from the horse-and-buggy age to the dawn of supersonic flight. Both brothers are buried in the family plot at Woodland Cemetery, Dayton, Ohio. John T. Daniels, the Coast Guardsman who took their famous first flight photo, died the day after Orville.

Competing claims

First powered flight claims are made for Clément Ader, Gustave Whitehead, Richard Pearse, and Karl Jatho for their variously documented tests in years prior to and including 1903. Claims that the first true flight occurred after 1903 are made for Traian Vuia and Alberto Santos-Dumont. Supporters of the post-Wright pioneers argue that techniques used by the Wright brothers disqualify them as first to make successful airplane flights. Those techniques were: A launch rail; skids instead of wheels; a headwind at takeoff; and a catapult after 1903. Supporters of the Wright brothers argue that proven, repeated, controlled, and sustained flights by the brothers entitle them to credit as inventors of the airplane, regardless of those techniques.

The aviation historian C.H. Gibbs-Smith was a supporter of the Wrights' claim to primacy in flight. He wrote that a barn door can be made to "fly" for a short distance if enough energy is applied to it; he determined that the very limited flight experiments of Ader, Vuia, and others were "powered hops" instead of fully controlled flights.