Istakhr

During the Arab conquest of Iran, Istakhr was noted for its stiff resistance, which resulted in the death of many of its inhabitants. Istakhr remained a stronghold of Zoroastrianism long after the conquests, and remained relatively important in the early Islamic era. It went into gradual decline after the founding of nearby Shiraz, before being destroyed and abandoned under the Buyids. Cursorily explored by Ernst Herzfeld and a team from the University of Chicago in the first half of the 20th century, much of Sasanian Istakhr remains unexcavated.

Etymology

"Istakhr" (also spelled Estakhr) is the New Persian form of the Middle Persian Stakhr (also spelled Staxr), and is believed to mean "strong(hold)". According to the Iranologist Ernst Herzfeld, who based his arguments on coins of the Persian Frataraka governors and Kings of Persis, the Middle Persian word in turn derives from Old Persian *Parsa-staxra ("stronghold of Pars"), owing to the city's close connections with the nearby Persepolis platform. Herzfeld interpreted the Aramaic characters "PR BR" inscribed on these coins as an abbreviation of Aramaic prsʾ byrtʾ ("the Fortress of Parsa"), which in turn may be the equivalent of the aforementioned Old Persian words. The abbreviation "ST", denoting Istakhr, also appears on Sasanian coins. Istakhr is attested in Syriac as Istahr and in Armenian as Stahr. It probably appears in the Talmud as Istahar.

Geography

Istakhr is located in Iran's southwestern province of Fars, historically known as Parsa (Old Persian), Pars (Middle Persian) and Persis (Greek), whence Persia. It lies in the valley of the Polvar River, between the Kuh-e Rahmat and the Naqsh-e Rostam, where the Polvar River valley opens into the plain of Marvdasht. This plain stretches near the platform of Persepolis.

History

Early history

In all likelihood, what became Istakhr was originally part of the settlements which surrounded the Achaemenid royal residences. Its religious importance as a Zoroastrian center was signified as early as the 4th century BC during the reign of Achaemenid King Artaxerxes II (r. 404-358). During his reign, he ordered the construction of a statue of Anahid and a temple near what would become Istakhr. This temple may be identified with the ruins of the temple mentioned by the 10th-century geographer al-Masudi as being located c. one parasang from Istakhr. According to the Iranologist Mary Boyce, the ruins of this temple probably belonged to the original Achaemenid building, which had been destroyed and pillaged by the invading Macedonians led by Alexander the Great (r. 336–323). Istakhr's foundation as a separate city took place very shortly after the decline of nearby Persepolis by Alexander. It appears that much of Persepolis' rubble was used for the building of Istakhr.

Frataraka and Kings of Persis

When Seleucus I (r. 305–280) died in 280 BC, the local Persians of Persis began to reassert their independence. The center of resistance appears to have been Istakhr, which with its surrounding hills provided better protection than the nearby former Achaemenid ceremonial capital of Persepolis. Furthermore, an important road, known as the "winter road", extended across Istakhr, leading from Persis to Isfahan through Pasargadae and Abada. The core of Istakhr as a city was located on the south and east side of the Polvar River. It flourished as the capital of the Persian Frataraka governors and Kings of Persis from the 3rd century BC to the early 3rd century AD.

Sasan, the eponymous ancestor of the later Sasanian dynasty, hailed from Istakhr and originally served as the warden of the important Anahid fire-temple within the city. According to tradition, Sasan married a woman of the Bazrangi dynasty, who ruled in Istakhr as Parthian vassals in the early 3rd century. In 205/6, Sasan's son Papak dethroned Gochihr, the ruler of Istakhr. In turn, Papak's sons, Shapur and Ardashir V, ruled as the last two Kings of Persis.

Sasanian Empire

In 224, Ardashir V of Persis founded the Sasanian Empire and became regnally known as Ardashir I (r. 224–242). Boyce states that the temple, which had been destroyed by the Macedonians centuries earlier, was restored under the Sasanians. She adds that according to Al-Masudi, who in turn based his writings on tradition, the temple had "originally been an 'idol-temple', which was subsequently turned into a fire temple by Homay, the legendary predecessor of the Achaemenid dynasty". It appears that in the early Sasanian period, or perhaps a bit before that, the Zoroastrian iconoclastic movement had resulted in the cult-image of Anahid being replaced by a sacred fire. Al-Masudi identified this sacred fire as "one of the most venerated of Zoroastrian fires". The identification of this temple at Istakhr with Anahid persisted, and the historian al-Tabari (died 923) stated that it was known as "the house of Anahid's fire".

The influential Zoroastrian priest Kartir was, amongst other posts, appointed as warden (pādixšāy) of "fire(s) at Stakhr of Anahid-Ardashir and Anahid the Lady" (ādur ī anāhīd ardaxšīr ud anāhīd ī bānūg) by Bahram II (r. 274–293). Boyce notes that given the high-ranking status of Kartir, the appointment of these posts signify that the sacred fires at Istakhr were held in very high regard.

Istakhr would reach its apex during the Sasanian era, serving as principal city, region, and religious centre of the Sasanian province of Pars. A center of major economic activity, Istakhr hosted an important Sasanian mint, abbreviated with the initials "ST" (Staxr) which produced coins from the reign of Bahram V (r. 420-438) until the fall of the dynasty, as well as the Sasanian royal treasury (ganj ī šāhīgān). This treasury is frequently mentioned in the Denkard and the Madayān i hazar dadestan. The treasury also held one of the limited copies of the Great Avesta, probably one of the very same copies from which the modern-day extant Avestan manuscript derives.

Arab conquest and caliphates

During the Muslim conquest of Pars, as part of the Arab conquest of Iran, the invaders first established headquarters at Beyza. The citizens of Istakhr firmly resisted the Arabs. The first attempt, in 640, led by Al-Ala'a Al-Hadrami was a complete failure. In 643, the Arabs conducted a new campaign led by Abu Musa al-Ash'ari and Uthman ibn Abu al-As which forced Istakhr to surrender. The people of Istakhr, however, quickly revolted and killed the Arab governor installed there. In 648/9, General Abdallah ibn Amir, governor of Basra, conducted another campaign which once again forced Istakhr to surrender after heavy fighting. The suppression of subsequent revolts resulted in the death of many Persians. However, the restive people of Istakhr revolted once again, which prompted the Arabs to undertake yet another campaign against Istakhr, in 649. This final campaign once again resulted in the death of many of its inhabitants. Istakhr's Sasanian fortress, located on the Marvdasht's "easternmost outcrop", became the location of the last resistance to the Arab conquest of Pars.

Istakhr remained a stronghold of Zoroastrianism long after the fall of the Sasanians. Many Arab-Sasanian coins and Reformed Umayyad coins were minted at Istakhr during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods. Istakhr remained "a fairly important place" in the early Islamic period. It was the site of an important fortress, which in Islamic times, "as no doubt earlier", often functioned as the treasury of the rulers of the city. The fortress is variously known as Qal-e-ye Estakhr ("Castle of Estakhr") or Estakhr-Yar ("Friend of Estakhr"). Under the Umayyad Caliphate, governors often resided at the castle; for instance, Ziyad ibn Abih resided at Istakhr's castle for a lengthy period during his struggle against Caliph Muawiyah I (r. 661–680).

Following the ascension of the Abbasids, the political center of Fars shifted gradually to Shiraz. This contributed heavily to the decline of Istakhr. However, the city is still mentioned in the wars between the Saffarids and the caliphal governors in Fars. On 11 April 890, Saffarid ruler Amr ibn al-Layth (r. 879-901) defeated the Caliphal governor Musa Muflehi at Istakhr. According to the Iranologist Adrian David Hugh Bivar, the last coin attributed to Istakhr is a coin supposedly minted by the Dulafids in 895/6.

Buyids and Seljuqs

The area became part of the Buyids in the first half of the 10th century. At the turn of the millennium, numerous travel writers and geographers wrote about Istakhr. In the mid-10th century, the travel writer Istakhri (himself a native), described it as a medium-sized town. The geographer Al-Maqdisi, writing some thirty years later, in 985, lauded the bridge over the river at Istakhr and its "fine park". He also noted the town's chief mosque was decorated with bull capitals. According to Boyce and Streck & Miles, this mosque was originally the same Sasanian temple where the ādur ī anāhīd ardaxšīr ("fire of Anahid-Ardashir") was located and where Yazdegerd III (r. 632–651) the last Sasanian King was crowned. However, according to the modern art historian Matthew Canepa, archaeological evidence shows that the mosque was built in the 7th century during Arab overlordship, and was, therefore, not a converted Sasanian temple. Al-Maqdisi also noted it was assumed that the mosque had originally been a fire temple, in which "pieces of carving from Persepolis had been used".

The region's cold climate created accumulations of snow at the top of the castle of Istakhr, which in turn melted into a cistern contained by a dam. This dam was founded by the Buyid 'Adud al-Dawla (r. 949-983) to create a proper water reservoir for the castle's garrison. According to a contemporaneous source, the Buyid Abu Kalijar (r. 1024–1048) found enormous quantities of silver and costly gems stored in the castle when he ascended it with his son and a valuer. The gold medal of Adud al-Dawla, dated 969/70, which depicts him wearing a Sasanian-style crown, may have been created at Istakhr.

The last numismatic evidence of Istakhr, denoting its castle rather than the city itself, dates to 1063. The coin in question was minted on the order of Rasultegin, an obscure Seljuq prince of Fars. However, Bivar notes that some coins attributed to other areas of Fars may in fact be coins from Istakhr. According to Bivar, who bases his arguments on the writings of Ibn al-Athir, the treasury of Istakhr held the treasures of earlier dynasties. Ibn al-Athir wrote that when Seljuq Sultan Alp Arslan (r. 1063-1072) conquered the castle of Istakhr in 1066/7, its governor handed him a valuable cup inscribed with the name of the mythical Iranian king Jamshid. Istakhr also held the Qal-e ye Shekaste, which functioned as the city's textile store, and the Qal-e ye Oshkonvan, the city's armory. Though the locations of these fortresses appear to be relatively distant from Istakhr's inner core, in the Medieval era they were "regarded as within the greater city" of Istakhr.

In the closing years of the Buyid Abu Kalijar, a vizier engaged in a dispute with a local landowner of Istakhr. Abu Kalijar, in turn, sent an army to Istakhr under Qutulmish who destroyed and pillaged the city. Istakhr never recovered and became a village with "no more than a hundred inhabitants".

In 1074, during Seljuq rule, a rebel named Fadluya had gained control over the province of Fars and had entrenched himself in Istakhr's castle. Nizam al-Mulk, the renowned vizier of the Seljuq Empire, subsequently besieged the fortress. Fadluya was captured and imprisoned in the fortress and executed a year later when he tried to escape. In later periods, the castle was often used "as a state prison for high officials and princes".

Period thereafter

In c. 1590, the castle of Istakhr was reportedly still in good condition and inhabited. Some time later, a rebel Safavid general took refuge in the castle. It was subsequently besieged by Safavid Shah ("King") Abbas the Great (r. 1588–1629), resulting in the destruction of the castle. According to the Italian traveler Pietro della Valle, who visited Istakhr in 1621, it was in ruins.

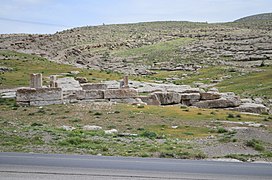

Excavation

In the first half of the 20th century, Istakhr was cursorily explored by Ernst Herzfeld followed by a team from the University of Chicago led by Erich Schmidt. The most detailed account of the ruins of Istakhr predating the 20th century excavations was made by the French duo Eugène Flandin and Pascal Coste in late 1840. Sasanian Istakhr remains largely unexcavated.

Gallery

Notable people

- Istakhri, geographer and writer

Notes

- ^ The native Old Persian name for Persepolis and Persis was Parsa.

References

- ^ Bivar 1998, pp. 643–646.

- ^ Streck & Miles 2012.

- ^ Shahbazi 2009.

- ^ Kia 2016, p. 83.

- ^ Boyce 1998, pp. 643–646.

- ^ Canepa 2018.

- ^ Daryaee 2012, p. 187.

- ^ Wiesehöfer 1986, pp. 371–376.

Sources

- Bivar, A. D. H. (1998). "Eṣṭaḵr i. History and Archaeology". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 6. pp. 643–646.

- Boyce, M.; Chaumont, M. L.; Bier, C. (1989). "Anāhīd". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 9. pp. 1003–1011.

- Boyce, Mary (1998). "Eṣṭaḵr ii. As a Zoroastrian Religious Center". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 6. pp. 643–646.

- Canepa, Matthew (2018). "Staxr (Istakhr) and Marv Dasht Plain". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2012). "The Sasanian Empire (224–651)". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199732159.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693912.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2009). "Persepolis". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Streck, M.; Miles, G.C. (2012). "Iṣṭak̲h̲r". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill Online.

- Wiesehöfer, Joseph (1986). "Ardašīr I i. History". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 4. pp. 371–376.

External links

- "Estakhr late-sasanid and proto-islamic (Sapienza's Archaeological Mission di Roma in Iran)". Sapienza Università di Roma. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27.