Karlóca

Name

In Serbian, the town is known as Sremski Karlovci (Сремски Карловци), in Croatian as Srijemski Karlovci, in German as Karlowitz or Carlowitz, in Hungarian as Karlóca, in Polish as Karłowice, in Romanian as Carloviț and in Turkish as Karlofça. The former Serbian name used for the town was Karlovci (Карловци), which is also used today, albeit unofficially. The name of the town in Serbian is plural.

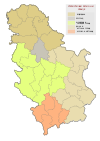

Geography

The town is situated along the Danube River, about 12km from Novi Sad and 75km from Belgrade, in the geographical region of Syrmia. The town of Sremski Karlovci is the only settlement in the municipality.

History

Ancient, medieval and early modern history

In ancient times, the Romans maintained a small fortress at this location. The town was first mentioned in historical documents in 1308 with the name Karom. The medieval fortress of Karom was built on the ruins of the ancient Roman one. Until 1521, Karom was a possession of Hungarian noble families, of whom the most well known were Báthory and Morović.

In 1521, Turkish military commander Bali-beg conquered Karom under the Ottoman Empire's invasion of Europe. During the next 170 years, the town was part of the Ottoman Empire. The Slavic name for the town – Karlovci, was first recorded in 1532/33. During Ottoman rule, the town was still predominately Serbian in ethnicity, with the smaller part of population composed of Muslims. According to the Ottoman defterler from 1545, the population of Karlovci numbered 547 Christian (Serb) houses. The city also had three Orthodox churches and a monastery. From 1557, it belonged to Eparchy of Belgrade and Srem of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć.

Habsburg Monarchy

Between 16 November 1698 and 26 January 1699, the town of Karlovci was the site of a congress that ended the hostilities between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League, a coalition of various European powers including Habsburg monarchy, Poland, Venice and Russia. The congress produced the Treaty of Karlowitz. It was the first time a round table was used in international politics.

After this peace treaty, the town was considered part of the Habsburg monarchy and was included in its Military Frontier. According to 1702 data, the population was composed of 215 Orthodox and 13 Catholic houses. By 1753, the population of the town numbered 3,843 people, of which 3,110 were classified as ethnic Serbs.

The town was the spiritual, political and cultural center of the Serbs in the Habsburg Monarchy. The Metropolitan of the Serbian Orthodox Church resided here. In the early 21st century, the Serbian Patriarch retains the title of Metropolitan of Karlovci.

The town had the earliest Serb (and Slavic in general) gymnasium (Serbian: gimnazija/гимназија, French: lycée), founded on 3 August 1791. Three years after this, the Orthodox seminary of Sremski Karlovci was founded here. It was the second-oldest Orthodox seminary in the world (after the Spiritual Academy in Kyiv), and it still operates.

At the Serb National Assembly in Karlovci in May 1848, Serbs declared the unification of the regions of Srem, Banat, Bačka, and Baranja (including parts of the Military Frontier) into the province of Serbian Vojvodina. In the late 18th century, the Habsburg monarchy had invited numerous settlers from Bavaria and southern Germany into some of these regions along the Danube, in order to repopulate the area and re-establish agriculture after the effects of the Ottoman invasion and disease. The Germans, who became known as Danube-Swabians, were allowed to keep their language and Catholic religion. For more than a century, they had fairly autonomous settlements.

The first capital of Serbian Vojvodina was in Karlovci; it was later moved to Zemun, Veliki Bečkerek, and Temišvar. At the same time the title of the Orthodox Metropolitan of Karlovci was raised to that of Patriarch.

When Serbian Vojvodina was in 1849 organized as the new province named Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar, the town of Karlovci was not included into this province. It was returned to the administration of the Military Frontier (a Petrovaradin regiment that was part of Slavonian Krajina). With the abolition in 1881 of the Military Frontier, the town was included in Syrmia County of Croatia-Slavonia, the autonomous kingdom within Kingdom of Hungary and Austria-Hungary.

An Orthodox Patriarchate of Karlovci operated after 1848 in Karlovci until 1920, after World War I. At that time, the position was joined with the Metropolitanate of Belgrade to form the united Serbian Orthodox Church, in what was then the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Between 1921 and 1944 the Patriarchate of Karlovci's Palace was the seat of the administration of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia.

Yugoslavia and Serbia (1918–onward)

In 1918, the town became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (also known as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia). In the summer of 1921, the town′s former palace of the Patriarch of Karlovci was used as the residence of Russian metropolitan Antony (Khrapovitsky). Together with some refugee bishops from Russia, he organised what a few years later was instituted as the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR). (Some critics called this ecclesiastical body the Karlovatsky Synod (Russian: Карловацкий синод), or ″Karlovatsky group″, also known in English as Synod of Karlovci.)

In 1922, the town became the headquarters of Russian White émigrés under the leadership of General Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel. In 1924 he set up the Russian All-Military Union, designed to include all Russian military émigrés the world over. Many emigres went to western Europe, especially France, and to the United States. A monument to Wrangel, sculpted by Vasiliy Azemsha, was unveiled in September 2007 in Karlovci.

Between 1929 and 1941, the town was part of Danube Banovina, a province of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. During World War II (1941–1944), after Nazi Germany's invasion of eastern Europe, the town was occupied by forces of the Axis Powers. It was attached to the Independent State of Croatia. During that time its name was changed to Hrvatski Karlovci. After the end of the war, most ethnic Germans were expelled from eastern Europe. The town became part of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, Serbia.

Between 1980 and 1989, Sremski Karlovci was one of the seven municipalities of the city of Novi Sad.

In January 2021 PM Igor Mirović announced a reconstruction of the facades of historically important buildings in Sremski Karlovci.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 5,350 | — |

| 1953 | 5,618 | +5.0% |

| 1961 | 6,390 | +13.7% |

| 1971 | 7,040 | +10.2% |

| 1981 | 7,547 | +7.2% |

| 1991 | 7,534 | −0.2% |

| 2002 | 8,839 | +17.3% |

| 2011 | 8,750 | −1.0% |

| 2022 | 7,872 | −10.0% |

| Source: | ||

According to the 2011 census, the municipality of Sremski Karlovci has 8,750 inhabitants.

Ethnic composition of the municipality of Sremski Karlovci:

| Ethnic group | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 6,820 | 77.94% |

| Croats | 576 | 6.58% |

| Hungarians | 182 | 2.08% |

| Yugoslavs | 71 | 0.81% |

| Germans | 63 | 0.72% |

| Montenegrins | 41 | 0.47% |

| Slovaks | 29 | 0.33% |

| Macedonians | 25 | 0.29% |

| Rusyns | 16 | 0.18% |

| Slovenes | 15 | 0.17% |

| Romani | 14 | 0.16% |

| Russians | 11 | 0.13% |

| Others | 969 | 11.07% |

| Total | 8,750 |

Economy

The following table gives a preview of total number of employed people per their core activity (as of 2017):

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 11 |

| Mining | 4 |

| Processing industry | 282 |

| Distribution of power, gas and water | 1 |

| Distribution of water and water waste management | 39 |

| Construction | 27 |

| Wholesale and retail, repair | 222 |

| Traffic, storage and communication | 71 |

| Hotels and restaurants | 125 |

| Media and telecommunications | 23 |

| Finance and insurance | 8 |

| Property stock and charter | 2 |

| Professional, scientific, innovative and technical activities | 31 |

| Administrative and other services | 92 |

| Administration and social assurance | 220 |

| Education | 284 |

| Healthcare and social work | 18 |

| Art, leisure and recreation | 14 |

| Other services | 66 |

| Total | 1,537 |

Politics

Until 1989 Sremski Karlovci formed one of the urban municipalities of the city of Novi Sad. After Novi Sad merged six of its municipalities into one Novi Sad municipality, the municipality of Sremski Karlovci held a referendum to separate from Novi Sad, and established a separate municipality independent from Novi Sad. Although Sremski Karlovci lies in Syrmia region, the municipality belongs in South Bačka District, and not in the Syrmia District, because of its close proximity to Novi Sad.

In the Serbian local elections held on 24 April 2016, Sremski Karlovci elected a new municipality parliament, ending the rule of the DS in the town. Nenad Milenković, of the Serbian progressive Party, was elected as the new mayor of the municipal parliament.

Schools

- Gymnasium of Karlovci

- Clerical High School of Saint Arsenije

- Faculty of management

- College of Applied Studies in Management and Business Communication

Buildings and structures

- Educational historical buildings:

- Gymnasium of Karlovci, first Serbian secondary school (gymnasium)

- Clerical High School of Saint Arsenije

- Administrative buildings:

- Religious buildings

- Other buildings

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Sremski Karlovci is twinned with:

Bardejov, Slovakia

Bardejov, Slovakia Karpoš, North Macedonia

Karpoš, North Macedonia Prnjavor, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Prnjavor, Bosnia and Herzegovina Tivat, Montenegro (2007)

Tivat, Montenegro (2007)

Gallery

-

City assembly building

-

Sabov-Dejanović's rococo house, 1790

-

An old Platanus, monument of nature protected by the state, in front of a church

-

City museum

-

Museum of beekeeping

-

Museum of Danube Swabians

-

A hotel in the centre

-

Faculty of management

-

Ecological center Miodrag Radulovacki

-

Monument dedicated to Duško Trifunović and viewpoint of Karlovci

See also

- Fruška Gora

- Syrmia

- List of places in Serbia

- List of cities, towns and villages in Vojvodina

- Spatial Cultural-Historical Units of Exceptional Importance

Notes

- ^ "Municipalities of Serbia, 2006". Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ "Насеља општине Сремски Карловци" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ "Census 2022: Total population, by municipalities and cities". popis2022.stat.gov.rs.

- ^ "Synod of Karlovci", Encyclopedia Britannica online

- ^ "Wrangel, Petr Nikolaevich, Baron", Encyclopedia 1914-1918

- ^ Споменик белом барону Politika, 13 September 2007.

- ^ "Sremski Karlovci obeležili 30 godina od ponovnog uspostavljanja samostalnosti". rtv.rs. 26 November 2019.

- ^ Vojvodine, Javna medijska ustanova JMU Radio-televizija. "Mirović: Sačuvaćemo kulturno-istorijski značaj Sremskih Karlovaca". JMU Radio-televizija Vojvodine. Retrieved 2021-01-14.

- ^ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова 2011. у Републици Србији" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "ОПШТИНЕ И РЕГИОНИ У РЕПУБЛИЦИ СРБИЈИ, 2018" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ Luković, Siniša (26 September 2016). "The people of Tiv visited the sister municipality in Vojvodina". vijesti.me.

- ^ "Fakultet za menadžment" (in Serbian). Retrieved 2021-01-14.

- ^ "Visoka škola za menadžment i poslovne komunikacije". Visoka škola strukovnih studija za menadžment i poslovne komunikacije (in Serbian). Retrieved 2021-01-14.

- ^ "Градови побратими". sremskikarlovci.rs (in Serbian). Sremski Karlovci. Retrieved 2020-01-07.

Reference

- Milorad Grujić, Vodič kroz Novi Sad i okolinu, Novi Sad, 2004.

- Slobodan Ćurčić, Broj stanovnika Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 1996.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Official website