Persepolitan

The earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. The city, acting as a major center for the empire, housed a palace complex and citadel designed to serve as the focal point for governance and ceremonial activities. It exemplifies the Achaemenid style of architecture. The complex was taken by the army of Alexander the Great in 330 BC, and soon after, its wooden parts were completely destroyed by fire, likely deliberately.

The function of Persepolis remains unclear. It was not one of the largest cities in ancient Iran, let alone the rest of the empire, but appears to have been a grand ceremonial complex that was only occupied seasonally; the complex was raised high on a walled platform, with five "palaces" or halls of varying size, and grand entrances. It is still not entirely clear where the king's private quarters actually were. Until recently, most archaeologists held that it was primarily used for celebrating Nowruz, the Persian New Year, held at the spring equinox, which is still an important annual festivity in Iran. The Iranian nobility and the tributary parts of the empire came to present gifts to the king, as represented in the stairway reliefs. It is also unclear what permanent structures there were outside the palace complex; it may be better to think of Persepolis as only one complex rather than a "city" in the usual sense.

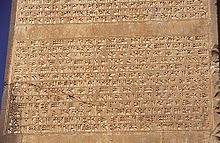

The exploration of Persepolis from the early 17th century led to the modern rediscovery of cuneiform writing and, from detailed studies of the trilingual Achaemenid royal inscriptions found on the ruins, the initial decipherment of cuneiform in the early 19th century.

Etymology

Persepolis is derived from the Greek Περσέπολις, Persepolis, a compound of Pérsēs (Πέρσης) and pólis (πόλις, together meaning "the Persian city" or "the city of the Persians"). To the ancient Persians, the city was known as Pārsa (Old Persian: 𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿), which is also the word for the region of Persia.

An inscription left in 311 AD by Sasanian Prince Shapur Sakanshah, the son of Hormizd II, refers to the site as Sad-stūn, meaning "Hundred Pillars". Because medieval Persians attributed the site to Jamshid, a king from Iranian mythology, it has been referred to as Takht-e-Jamshid (Persian: تخت جمشید, Taxt e Jamšīd; [ˌtæxtedʒæmˈʃiːd]), literally meaning "Throne of Jamshid". Another name given to the site in the medieval period was Čehel Menâr (Persian: چهل منار, "Forty Minarets"), transcribed as Chilminara in De Silva Figueroa and as Chilminar in early English sources.

Geography

Persepolis is near the small river Pulvar, which flows into the Kur River. The site includes a 125,000 m (1,350,000 sq ft) terrace, partly artificially constructed and partly cut out of a mountain, with its east side leaning on Rahmat Mountain.

History

Construction

Archaeological evidence shows that the earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. André Godard, the French archaeologist who excavated Persepolis in the early 1930s, believed that it was Cyrus the Great who chose the site of Persepolis, but that it was Darius I who built the terrace and the palaces. Inscriptions on these buildings support the belief that they were constructed by Darius.

With Darius I, the sceptre passed to a new branch of the royal house. The country's true capitals were Susa, Babylon and Ecbatana. This may be why the Greeks were not acquainted with the city until Alexander the Great took and plundered it.

Darius I's construction of Persepolis was carried out parallel to that of the Palace of Susa. According to Gene R. Garthwaite, the Susa Palace served as Darius' model for Persepolis. Darius I ordered the construction of the Apadana and the Council Hall (Tripylon or the "Triple Gate"), as well as the main imperial Treasury and its surroundings. These were completed during the reign of his son, Xerxes I. Further construction of the buildings on the terrace continued until the downfall of the Achaemenid Empire. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, the Greek historian Ctesias mentioned that Darius I's grave was in a cliff face that could be reached with an apparatus of ropes.

Around 519 BC, construction of a broad stairway was begun. Grey limestone was the main building material used at Persepolis. The uneven plan of the terrace, including the foundation, acted like a castle, whose angled walls enabled its defenders to target any section of the external front.

-

General view of the Persepolis

-

Aerial architectural plan of Persepolis

Destruction

After invading Achaemenid Persia in 330 BC, Alexander the Great sent the main force of his army to Persepolis by the Royal Road. Diodorus Siculus writes that on his way to the city, Alexander and his army were met by 800 Greek artisans who had been captured by the Persians. Most were elderly and suffered some form of mutilation, such as a missing hand or foot. They explained to Alexander the Persians wanted to take advantage of their skills in the city but handicapped them so they could not easily escape. Alexander and his staff were disturbed by the story and provided the artisans with clothing and provisions before continuing on to Persepolis. Diodorus does not cite this as a reason for the destruction of Persepolis, but it is possible Alexander started to see the city in a negative light after this encounter.

Upon reaching the city, Alexander stormed the Persian Gates, a pass through Zagros Mountains. There Ariobarzanes of Persis successfully ambushed Alexander the Great's army, inflicting heavy casualties. After being held off for 30 days, Alexander the Great outflanked and destroyed the defenders. Ariobarzanes himself was killed either during the battle or during the retreat to Persepolis. Some sources indicate that the Persians were betrayed by a captured tribal chief who showed the Macedonians an alternate path that allowed them to outflank Ariobarzanes in a reversal of Thermopylae. After several months, Alexander allowed his troops to loot Persepolis.

Around that time, a fire burned "the palaces" or "the palace".

It is believed that the fire which destroyed Persepolis started from Hadish Palace, which was the living quarters of Xerxes I, and spread to the rest of the city. It is not clear if the fire was an accident or a deliberate act of revenge for the burning of the Acropolis of Athens during the second Persian invasion of Greece. Many historians argue that, while Alexander's army celebrated with a symposium, they decided to take revenge against the Persians. If that is so, then the destruction of Persepolis could be both an accident and a case of revenge. The fire may also have had the political purpose of destroying an iconic symbol of the Persian monarchy that might have become a focus for Persian resistance.

Several much later Greek and Roman accounts (including Arrian, Diodorus Siculus and Quintus Curtius Rufus) describe that the burning was the idea of Thaïs, mistress of Alexander's general Ptolemy I Soter, and possibly of Alexander himself. She is said to have suggested it during a very drunken celebration, according to some accounts to revenge the destruction of Greek sanctuaries (she was from Athens), and either she or Alexander himself set the fire going.

The Book of Arda Wiraz, a Zoroastrian work composed in the 3rd or 4th century, describes Persepolis' archives as containing "all the Avesta and Zend, written upon prepared cow-skins, and with gold ink", which were destroyed. Indeed, in his Chronology of the Ancient Nations, the native Iranian writer Biruni indicates unavailability of certain native Iranian historiographical sources in the post-Achaemenid era, especially during the Parthian Empire. He adds: "[Alexander] burned the whole of Persepolis as revenge to the Persians, because it seems the Persian King Xerxes had burnt the Greek City of Athens around 150 years ago. People say that, even at the present time, the traces of fire are visible in some places."

On the upside, the fire that destroyed those texts may have preserved the Persepolis Administrative Archives by preventing them from being lost over time to natural and man-made events. According to archaeological evidence, the partial burning of Persepolis did not damage what are now referred to as the Persepolis Fortification Archive tablets, but rather may have caused the eventual collapse of the upper part of the northern fortification wall, preserving the tablets until their recovery by the Oriental Institute's archaeologists.

After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire

In 316 BC, Persepolis was still the capital of Persia as a province of the great Macedonian Empire (see Diodorus Siculus xix, 21 seq., 46; probably after Hieronymus of Cardia, who was living about 326). The city must have gradually declined in the course of time. The lower city at the foot of the imperial city might have survived for a longer time; but the ruins of the Achaemenids remained as a witness to its ancient glory.

The nearby Estakhr gained prominence as a separate city very shortly after the decline of Persepolis. It appears that much of Persepolis' rubble was used for the building of Istakhr. At the time of the Muslim invasion of Persia, Estakhr offered a desperate resistance. It was still a place of considerable importance in the first century of Islam, although its greatness was speedily eclipsed by the new metropolis of Shiraz. In the 10th century, Estakhr dwindled to insignificance. During the following centuries, Estakhr gradually declined, until it ceased to exist as a city.

Archaeological research

Odoric of Pordenone may have passed through Persepolis on his way to China in 1320, although he mentioned only a great, ruined city called "Comerum". In 1474, Giosafat Barbaro visited the ruins of Persepolis, which he incorrectly thought were of Jewish origin. Hakluyt's Voyages included a general account of the ruins of Persepolis attributed to an English merchant who visited Iran in 1568. António de Gouveia from Portugal wrote about cuneiform inscriptions following his visit in 1602. His report on the ruins of Persepolis was published as part of his Relaçam in 1611.

In 1618, García de Silva Figueroa, King Philip III of Spain's ambassador to the court of Abbas I, the Safavid monarch, was the first Western traveler to link the site known in Iran as "Chehel Minar" as the site known from Classical authors as Persepolis.

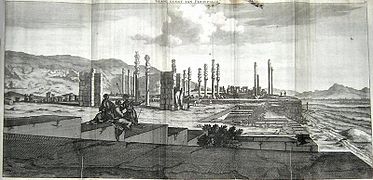

Pietro Della Valle visited Persepolis in 1621, and noticed that only 25 of the 72 original columns were still standing, due to either vandalism or natural processes. The Dutch traveler Cornelis de Bruijn visited Persepolis in 1704.

-

Sketch of Persepolis from 1704 by Cornelis de Bruijn

-

Drawing of Persepolis in 1713 by Gérard Jean-Baptiste

-

Drawing of the Tachara by Charles Chipiez

-

The Apadana by Charles Chipiez

-

Apadana detail by Charles Chipiez

-

Persepolis by Jean Chardin, 1711

-

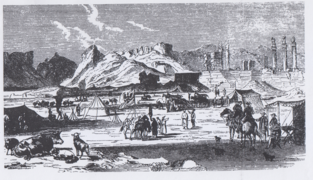

Prussia board at Persepolis, 1862–1863

-

The first scientific explorations in Persepolis were conducted by Ernst Herzfeld in 1931

-

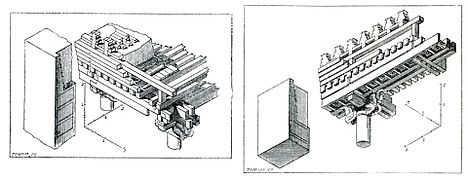

The design and details of the columns of Persepolis

-

Roof design of palaces at Persepolis

-

The design of the Throne Hall, Persepolis

The fruitful region was covered with villages until its frightful devastation in the 18th century; and even now it is, comparatively speaking, well cultivated. The Castle of Estakhr played a conspicuous part as a strong fortress, several times, during the Muslim period. It was the middlemost and the highest of the three steep crags which rise from the valley of the Kur, at some distance to the west or northwest of the necropolis of Naqsh-e Rustam.

The French voyagers Eugène Flandin and Pascal Coste are among the first to provide not only a literary review of the structure of Persepolis, but also to create some of the best and earliest visual depictions of its structure. In their publications in Paris, in 1881 and 1882, titled Voyages en Perse de MM. Eugene Flanin peintre et Pascal Coste architecte, the authors provided some 350 ground breaking illustrations of Persepolis. French influence and interest in Persia's archaeological findings continued after the accession of Reza Shah, when André Godard became the first director of the archeological service of Iran.

In the 1800s, a variety of amateur digging occurred at the site, in some cases on a large scale.

The first scientific excavations at Persepolis were carried out by Ernst Herzfeld and Erich Schmidt representing the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. They conducted excavations for eight seasons, beginning in 1930, and included other nearby sites.

Herzfeld believed that the reasons behind the construction of Persepolis were the need for a majestic atmosphere, a symbol for the empire, and to celebrate special events, especially the Nowruz. For historical reasons, Persepolis was built where the Achaemenid dynasty was founded, although it was not the center of the empire at that time.

Excavations of plaque fragments hint at a scene with a contest between Herakles and Apollo, dubbed A Greek painting at Persepolis.

Architecture

Persepolitan architecture is noted for its use of the Persian column, which was probably based on earlier wooden columns.

The buildings at Persepolis include three general groupings: military quarters, the treasury, and the reception halls and occasional houses for the King. Noted structures include the Great Stairway, the Gate of All Nations, the Apadana, the Hall of a Hundred Columns, the Tripylon Hall and the Tachara, the Hadish Palace, the Palace of Artaxerxes III, the Imperial Treasury, the Royal Stables, and the Chariot House.

Remains

Ruins of a number of colossal buildings exist on the terrace. All are constructed of dark-grey marble. Fifteen of their pillars stand intact. Three more pillars have been re-erected since 1970. Several of the buildings were never finished.

Behind the compound at Persepolis, there are three sepulchers hewn out of the rock in the hillside.

-

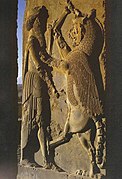

A bas-relief from the Apadana Palace depicting Delegations including Lydians and Armenians bringing their famous wine to the king.

-

Achaemenid plaque from Persepolis, kept at the National Museum of Iran.

-

Relief of a Median man at Persepolis.

-

Objects from Persepolis kept at the National Museum of Iran

-

The head of a Lamassu from Persepolis, kept at the National Museum of Iran

-

Door-Post Socket

-

The Great Double Staircase at Persepolis

-

A bas-relief at Persepolis, representing a symbol in Zoroastrianism for Nowruz.

-

The discipline of the reliefs.

-

Tablets of Xerxes, kept at the National Museum of Iran

-

One of the staircases of Persepolis, kept at the National Museum of Iran

-

One of the four existing statues of Penelope was discovered at Persepolis, and is kept at the National Museum of Iran

The Gate of All Nations

The Gate of All Nations, referring to subjects of the empire, consisted of a grand hall that was a square of approximately 25 m (82 ft) in length, with four columns and its entrance on the Western Wall.

-

The Gate of All Nations, Persepolis

-

A Lamassu at the Gate of All Nations

-

The position of three languages inscriptions on The Gate of All Nations, Persepolis

-

The two Lamassu at the Gate of All Nations.

-

The Gate of All Nations in 1905.

The Apadana Palace

Darius I built the greatest palace at Persepolis on the western side of platform. This palace was called the Apadana. The King of Kings used it for official audiences.

Foundation tablets of gold and silver were found in two deposition boxes in the foundations of the Palace. They contained an inscription by Darius in Old Persian cuneiform, which describes the extent of his Empire in broad geographical terms, and is known as the DPh inscription:

![A bas-relief from the Apadana Palace depicting Delegations including Lydians and Armenians[42] bringing their famous wine to the king.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/68/Persepolis_stairs_of_the_Apadana_relief.jpg/269px-Persepolis_stairs_of_the_Apadana_relief.jpg)

![A bas-relief at Persepolis, representing a symbol in Zoroastrianism for Nowruz.[a]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/36/PersepolisNegareh.jpg/291px-PersepolisNegareh.jpg)